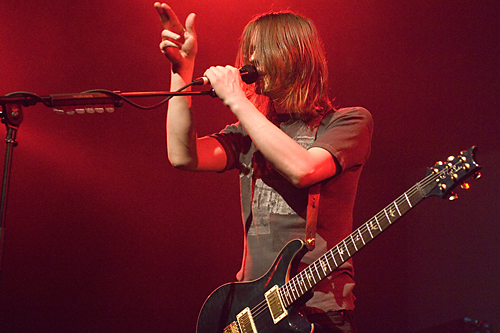

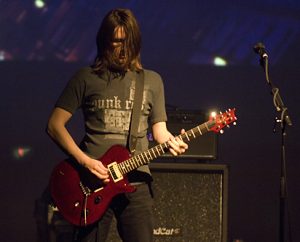

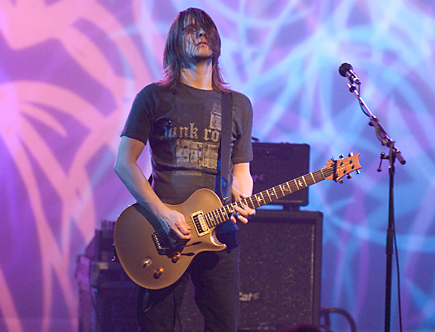

Steven Wilson is one of our greatest musical heroes today. As the guitarist, lead vocalist, and principle songwriter for Porcupine Tree, he defines the sound and style of his increasingly popular progressive rock band. The simplest description of him (for those of you who haven’t yet immersed yourself in the band’s music) might be to say, “If David Gilmour had the urge to play a little metal now and then.” But of course for those of you already familiar with Wilson, you know there’s more – so much more.

A self-professed control-freak, Steven also engineers and produces music. Not just for Porcupine Tree, though. He has produced, mixed, and recorded other artists ranging from Opeth to Anja Garbarke to John Wesley, and has made guest contributions as a producer, mixer, or musician for artists ranging from Marillion to OSI (supergroup featuring Dream Theater’s Mike Portnoy).

Wilson’s most significant role outside of Porcupine Tree, however, is the role he plays as co-lead singer, guitarist, songwriter, and producer for the pop rock band, Blackfield. This band, partially co-fronted by Israeli singer Aviv Geffin and backed by some other great Israeli musicians, has the sonic character and style of Porcupine Tree, but songs are a little bit more commercially focused – you won’t find fifteen minute epics on a Blackfield album or monster double-kick drum breaks.

Don’t be misled by Wilson’s claims that Blackfield is his pop band while Porcupine Tree is his progressive band, though. When a master progressive rock songwriter pens a pop song, you know it’s going to be light years more interesting than generic radio fodder. [For a review of the latest Blackfield CD, see our June CD reviews.]

We had a chance to talk with Steven Wilson during the Fear of a Blank Planet tour about the latest Porcupine Tree CD, recording, performing, and more.

I never really intended for it to be anything more than a one-off kind of studio project

MPc: Fear of a Blank Planet paints a really horrific picture of children today. Tell us a little bit about the inspiration behind the new album.

SW: Well it was a combination of things. I think first and foremost it’s a kind of general feeling that I suppose a lot of people feel as they get older, of gradually feeling more and more alienated from the younger generation, and specifically kind of the way that most young people now seem to live their lives very much dependent on information technology and the Internet. Of course they’ve all grown up with the Internet, but not just the Internet. There are also things like iPods, cell phones, PlayStations, xBoxes… there’s the whole concept now of prescription drugs for treating things that just didn’t even exist when I was a teenager. I never heard of things like Attention Deficit Disorder and Bi-polar Disorder.

Now we have fancy drugs [to treat these problems] and we almost have ways of legitimizing some of these things when I’m not sure that we should, so that was one thing. The other thing was I read a book by Bret Easton Ellis called Lunar Park in which the central character Robbie, this ten-year-old kid, was very much my inspiration for the main character in Fear of a Blank Planet. He’s a kid who basically spends most of his time in his room with the curtains closed whether it’s nighttime or daytime, can barely form a sentence, treats his parents with complete disdain, boredom, spends most of his time on PlayStation or on the Internet downloading pornography, music and movies, and just kind of… you know… that word blank seems to sum up that whole kind of existence, and I do genuinely have a fear that we have a problem, having a generation of kids that will be like that. Not all of them, obviously, but the majority will be like that. They will think things like American Idol and Big Brother are their kind of cultural touchstones, and that’s kind of depressing, and that’s why the record is depressing.

Now we have fancy drugs [to treat these problems] and we almost have ways of legitimizing some of these things when I’m not sure that we should, so that was one thing. The other thing was I read a book by Bret Easton Ellis called Lunar Park in which the central character Robbie, this ten-year-old kid, was very much my inspiration for the main character in Fear of a Blank Planet. He’s a kid who basically spends most of his time in his room with the curtains closed whether it’s nighttime or daytime, can barely form a sentence, treats his parents with complete disdain, boredom, spends most of his time on PlayStation or on the Internet downloading pornography, music and movies, and just kind of… you know… that word blank seems to sum up that whole kind of existence, and I do genuinely have a fear that we have a problem, having a generation of kids that will be like that. Not all of them, obviously, but the majority will be like that. They will think things like American Idol and Big Brother are their kind of cultural touchstones, and that’s kind of depressing, and that’s why the record is depressing.

MPc: Porcupine Tree has come a long way from being your one-man-band recording project to becoming one of the most popular progressive rock bands today. How did you go about making the transition from recording project to band?

SW: Well to be honest it was a very natural transition. This whole band has been very… it’s been almost like every step of the way has been a bonus because I never really intended for it to be anything more than a one-off kind of studio project, and yet at each stage it’s become a victim of its own success.

I made the first album and then there was a great response to that, so I carried on recording and making records, and then at a certain point there was a demand for us to play live so I put the band together. Really, every step of the way it’s just been learning from experience, learning from mistakes, and, I guess, also a sense of feeling that there’s still so much work to do and there’s still so much to explore musically and lyrically.

That’s, at the end of the day, what keeps it fresh, but I would have to say that right from the beginning, if I’d known that it was ever gonna’ get to this stage I would’ve been absolutely in shock because none of this was planned. Every step of the way, as I said, has been an unexpected development, pretty much because of the success of the records, and then later on the touring. I always loved the idea of a band – I mean, I think I love the kind of romantic idea of being in a rock band and on the road, so that was always kind of my dream anyway, so I’m very happy that that’s what it has developed into ultimately.

MPc: Were you originally thinking that your career path would be as a producer, or did the work in producing come as a result of the success from Porcupine Tree? Which came first?

“I certainly never thought of myself as a performer

or a singer or a guitar player.”

SW: I never thought of myself as working with other musicians. I mean, I always thought of myself as a producer and a songwriter – I certainly never thought of myself as a performer or a singer or a guitar player. Those were things that came later on because I had to learn how to do those things in order to realize what I was hearing in my head. What I originally fell in love with when I was a kid was the whole idea of making records. I wanted to learn how to make records and so whatever it took in order to achieve that, I was going to find out how to do that. For me that meant having to learn to play guitar, having to learn how to sing, having to learn how to record drums and guitars, having to learn how to program, having to learn how to mix, having to learn how to master. All of those things I’ve learned in a kind of idiot savant way because, well, number one: because I’m a control freak, and I hate to give any of those steps… I hate to put any of those things in the hands of other people, and secondly: because I had to, because making records is the whole thing for me. It’s everything from writing to designing the packaging to thinking about even things like the kind of paper the booklet is going to be printed on, really, right down to the finest details of releasing a record. That’s what I love to do.

MPc: Certainly the albums are extremely thought out conceptually from start to finish. Your albums are very much “listening records” that tell a story that evolves from the beginning to the end.

SW: Right.

MPc: Like many people, particularly in America, I first discovered Porcupine Tree with In Absentia and was immediately hooked. Is the songwriting process collaborative or do you basically bring all the songs to the band?

MPc: Like many people, particularly in America, I first discovered Porcupine Tree with In Absentia and was immediately hooked. Is the songwriting process collaborative or do you basically bring all the songs to the band?

SW: It’s kind of both. I think with all of the records, I start the ball rolling very much because I have a lyrical idea or a subject matter that I kind of decide I want to hang the rest of the record around, and then I will tend to write a batch of songs. In the past, that batch of songs would tend to become the album, but on the last couple of records we’ve actually spent time towards the end of the writing process writing as a band. On Deadwing, for example, that [collaboration] gave us the tracks “Halo” and “Glass Arm Shattering.” On this record, it gave us the track “Way Out of Here,” which I think is one of the best tracks on the record.

So it’s definitely a mixture these days, but I guess I’d say seventy-five percent of it, eighty percent of it is still (pretty much) me writing in a kind of solitary way trying to get a shape to the album, trying to get a theme (or feel?) to the album, trying to find the center of the record. And then when I feel I’ve found that record and I’ve got the majority of it, I go into a band writing situation and see what else will come out of that process, and so far, so good. It’s been quite rewarding to do that

MPc: Do you start with the lyrics or do you typically start off with music and let that inspire your darker writing?

SW: I usually have some theme that I know I want to write about, and I think that’s important because without any theme the music doesn’t really have a sense of direction. It’s nice to think that the music is somehow directly inspired by and somehow responding to lyrical things and I definitely think that’s the case with this album. I already knew that I wanted to write an album about this whole issue that I talked about. I didn’t necessarily have any lyrics, per se, but I had a very strong conception.

MPc: Now let’s talk a little bit about the recording process. I know that in recording your guitars for the past few records you primarily went direct using Line 6 Pod technology, but then live, at least for the past couple of tours, I notice you’ve been playing amazing Bad Cat amplifiers. Can you share with us your approach to recording guitars and how that may or may not be changing or evolving over time?

SW: Well in the early days, I was pretty much forced to find ways to create guitar sounds without relying on expensive equipment. I had very basic equipment when I started out, but also couldn’t rely on being able to go into studios and crank up amps and try different microphone techniques and all that stuff, so I was kind of in a situation where I had to create sounds using direct methods, and that’s how I got so familiar with using Line 6 stuff.

I know some people are a bit snobby about using guitar processing. They think that if you’re not using an amp and if you’re not cranking it up and miking it up then how can you be a good guitar player, but I’m a great believer that everything has its strengths. Every piece of technology you can create unique sounds from, so what I tend to do when I’m writing and when I’m demoing, I’m obviously doing it in a very basic way, sometimes just on my laptop in my apartment, so I’m using the Pods to create guitar tones very quickly and intuitively. Then what I find later in the session is a lot of those sounds have become integral to the way the track has developed, to the character of the track, and to the personality of the track, so it’s just not possible to recreate them.

And that’s what I mean by the Pod having its own kind of signature, its own kind of personality. Later on in the session, the more kind of generic heavy guitar tones, of course, you start cranking up Marshalls and you mic up Marshalls, and you get those better sounds, but some of the quirkier sounds I’m thinking of, definitely you know those are the kind of things that survive from the demo when I’m just using the Pod. And I do think it has a really distinctive quality.

MPc: Something that’s an identifiable part of the Porcupine Tree sound involves some very metal style guitar rhythms that you play, but they’re played with a very unique tone that isn’t as heavy as what metal guys would use. I’m wondering if you can tell us a little bit about the amps you’re using and how you’re getting that kind of tone?

SW: Well gosh, I’m not really sure, to be honest. I can tell you what we do, but I’m not sure it’s something that we do deliberately. I guess it’s just what intuitively is a sound that we gravitate towards. [On Fear of a Blank Planet] I used [Gibson] Les Paul and Paul Reed Smith guitars. We were going through… we had the Bad Cat Hot Cat in the studio, we also had a Diesel head, and were just going through a pretty generic 4x12 Celestion Greenback Marshall cab. We had a couple of mics on there: we had a 58 and a 414.

What I like to do, which I think some more heavy bands shy away from, is that they don’t overdub as much as I do. I tend to track things many times so you get a very rich, more musical tone. I think if you’re more purist, I know some bands for example are very purist about tracking their guitars twice so that they can reproduce it live. But if you keep layering guitars they begin to sound more textured and (I guess) a little bit more processed in a way, but they have a more musical quality sometimes

MPc: We saw your performance in New York City just a few nights ago (which was a fabulous show) and noticed that both yourself and John Wesley had TC Electronic G-Systems on the floor. When did you make the switch to starting to incorporate a G-System?

SW: Last year we did a short tour to promote our DVD and I’m just thinking maybe we used it on the Arriving Somewhere tour… it could be as long ago as mid-2005, halfway through the Deadwing touring cycle, and I can tell you exactly why we did it. It was simply because… it’s a nice piece of gear, but actually the practical reason was we could no longer afford to fly around our custom rigs. I used to have a huge Bob Bradshaw custom-made rig and it’s fantastic, but it was so heavy and it was so expensive [to cart] particularly when you’re doing things like fly-in/fly-out festival shows in Europe or in America. We would sometimes get like eight, nine, ten-thousand dollar freighting bills just for doing a single show!

We got to the stage where we thought, “Well no, we can’t do this, We’ve gotta’ find a way to make the guitar systems more portable, more mobile without sacrificing any of that kind of flexibility and quality” and Wes actually discovered the G-System before I did, and he recommended it to me. Every piece of gear has its own little kind of quirks that you have to get around, and the G-System has one problem which I’ve had to solve with another pedal board, a gig rig pedal board, which is that it’s too slow in switching from channel to channel, and so I’ve had to have another pedal board which bypasses the G-System when I need to get the direct-inject crunchy sound off the hot channel on the amp. So they’ve all got their little quirks but you kind of work around those things and you get used to them, and it’s working pretty well at the moment. And, it’s a lot more portable as a kind of system.

MPc: Speaking of John Wesley, he strikes me as (sort of) the unofficial sixth member of the band because I always see him on tour with you guys, and sometimes making a small appearance on a recording.

MPc: Speaking of John Wesley, he strikes me as (sort of) the unofficial sixth member of the band because I always see him on tour with you guys, and sometimes making a small appearance on a recording.

SW: Yeah, he’s become very important to the large sound because as you see from the albums, what’s basically happened over the last few albums is it’s become much more… the guitar parts have become much more layered, more complex, and so have the vocals. I couldn’t imagine now going out and doing shows without having that extra guitar player and extra singer there and Wes just fits in so well. We all get on really well with him, and he totally fits in with the musical style.

MPc: Richard Barbieri’s keyboard parts are certainly an integral part of the Porcupine Tree sound. Can you talk about your philosophy and approach to keyboards and synthesizer in your music?

SW: Well it’s very simple, really. We don’t have anything that is competing with the guitar parts, so what the keyboards tend to do is play a more textural role. Now Richard is not your kind of technical player. He’s never been interested in that kind of playing. He comes much more from the Brian Eno approach to performing on synthesizers, which is that it’s all about creating sounds and textures, sculpting in sound. It’s not about playing complex parts and runs, so his role, he’s kind of found a space in the music where he just fits in perfectly, creating these extraordinary textures which I think give the music a lot of…

“I think what’s really special and a lot of what’s really original about Porcupine Tree comes in the way that we do use textures.”

I think what’s really special and a lot of what’s really original about Porcupine Tree comes in the way that we do use textures, and we do use keyboard textures. It’s what gives the music a lot of space. It’s what gives the music a lot of depth. Particularly when you hear the albums in their entirety you really begin to notice the detail in the way the keyboards are used. And I think that another thing that takes us away from moving towards a kind of generic progressive music, or generic metal music, is the way that we incorporate keyboards into the band. And we’re also big fans of the original timeless organic sounds like Mellotrons and Fender Rhodes and grand piano and Wurlitzers – we love all those sounds, too.

MPc: In your live show, the video has become an essential ingredient – it’s a further extension or a part of the story, and something that we were so impressed by at the NY show was how well you guys have nailed synchronizing the video story to your live music. So can you tell us a little bit about the creation of the video and then the technical aspects of executing your show?

SW: Well, we’ve been very lucky in that about three albums ago we were contacted by a Danish photographer, filmmaker, artist called Lasser Hoile, and the first thing he presented to us was what became the album cover to In Absentia, and since then he’s really become an invaluable part of the band. He’s taken promo shots, he’s made videos, he makes most of the films that we project live, and he’s really become the kind of visual conceptualist to the band. You mentioned earlier about John Wesley being like the fifth member of the band – Lasser could just as easily claim to be, because the visual identity of the band now is just so strong and it’s really down to him.

He’s done the last three album covers, he’s created all of the imagery for the booklet of the new album cover, films, and I get on really well with Lasser and we have a lot in common. We both have a lot of passion for similar kinds of movies, and that’s very important because when we talk about visual ideas I know that when I say something to him, he totally understands where I’m coming from, and we both know we’re on the same page. So with this album, I sat down with him and I went through all of my lyrical ideas. We talked about the concept, we talked about the ideas behind the album and the issues that I was trying to talk about, and he totally got it. We actually talked about some very specific stories as well that we both heard about.

Nowadays we can really just leave Lasser to create those films and he just does such a marvelous job and we have our own projector, which we take around with us [on tour]. Very rarely, sometimes we have to drop the projections because it’s just not physically possible, but I think you’re right – now it’s such an integral part of the show I think it would be a shame not to have it.

MPc: So how do you keep the video in such perfect sync with the band? What tools are you using?

SW: Basically Gavin, our drummer, is playing to a click track. We use two… well actually we’ve just moved to one Apple Macintosh. We used to run it on two Apple Macs, but we’ve just recently managed to get a Mac that’s powerful enough to run everything – the MIDI information and the video information on one computer. We’re using Logic Audio for the click track, and that also sends out MIDI information to a program called ArKaos, which is the program that’s actually controlling all of the visual information.

MPc: You guys really executed that beautifully, like with the synchronized words behind the song “Halo” and the timing of the film during the Fear section of the show.

SW: We’ve worked it out over a period of tours by trial and error, the best way to do it, and I think we’ve hit on a really nice way to do it now.

SW: We’ve worked it out over a period of tours by trial and error, the best way to do it, and I think we’ve hit on a really nice way to do it now.

MPc: Turning our attention back to the music, obviously you’re using the G-System live, but what did you use for effects when recording Fear of a Blank Planet?

SW: Wes has a huge collection of vintage guitar pedals, so we were using everything from Electro Harmonix flangers to Ratt distortion pedals and lots of other things that I can’t even remember what they were called. He has a big collection, so I actually flew over to Florida to his studio for a few days to work on sounds for the album.

The guitars were going through a lot of vintage stuff, but also I’m a big fan of, not only the Pod which we talked about, but I’m also a big fan of plug-ins. I think you can do some amazing stuff with the new generation of plug-ins. So some of the sounds are created by post production using plug-ins either in the mix or in a kind of destructive way, in a [Pro Tools] Audio Suite way. So I don’t have any rules…

MPc: What are some of your favorites plug-ins?

SW: There’s a suite of plug-ins [Digidesign’s D-Fi collection] of which one is called Lo Fi, which is fantastic. I love Lo Fi – it’s the kind of thing that Trent Reznor uses a lot where he gets those really fizzy digital fucked-up sounds. It basically enables you to take a sound, not just a guitar sound but any sound, and reduce the bit rate and the sample rate until you get that kind of wonderful quantization noise. Well, it’s not always wonderful, but it can be wonderful used in the right way, so I used that a lot to get really fizzy kinds of sounds, almost digital distortion sounds, so that’s one of my favorites.

I love the Line 6 Echo Farm, which is the old kind of tape delay simulator – that’s wonderful. I’m using that all the time. I like being able to add things like warble and tape hiss and stuff to the signal – it just makes it sound more organic somehow. And, I’m a big, big fan of the Focusrite EQ and the Focusrite compression, the D2 and the D3. They’re, I think, probably my favorites.

MPc: What’s your microphone of choice for recording vocals?

SW: I’ve used for many, many years Neumann U-87. Actually, since the beginning I’ve used that, and I still use it. It’s the only mic I use.

MPc: Many of our readers may not yet be familiar with your other band, Blackfield. Can you compare and contrast your work in Porcupine Tree with what you do musically in Blackfield?

“Blackfield has almost become, in a way, the alter ego of Porcupine Tree”

SW: Yeah, it’s funny because Blackfield has almost become, in a way, the alter ego of Porcupine Tree for myself in the sense that it’s also enabled me to liberate Porcupine Tree a little bit from this idea that Porcupine Three maybe should be writing shorter, more concise songs, which we have dabbled with in the past. I have occasionally, you know, written short pieces for Porcupine Tree, but I don’t think that’s where Porcupine Tree’s strength lies. I think our strength definitely lies in the longer, more complex pieces.

And so in a way, Blackfield has given me another kind of outlet for writing more straightforward pop song material, and I think Blackfield does it in a more convincing way somehow – it’s what Blackfield are about. And so it’s kind of liberated Porcupine Tree from that side if you like, and it works really well. The combination of the two acts (for me) works great in terms of I can write stuff in a more complex way or in a more straightforward way, and I now feel like there’s a perfect outlet for either of those styles.

MPc: We only recently started listening to Blackfield, and it’s interesting hearing about some of the differences because there is definitely an overlap in there. Certainly, a song like “Lazarus,” for example, could just as easily have been a Blackfield song.

SW: Right. I think that’s one of the examples where you’ll notice that there really isn’t anything like that on the new Porcupine Tree record. It is a more complex, intense record, and a song like “Lazarus,” which might have been on this record in the past, as you say, it’s more likely the kind of thing now I would give to Blackfield. I think it somehow just makes each project more pure.

MPc: Being a relative late-comer to the Porcupine Tree fold, I don’t really know much about your personal influences. Historically who were some bands that inspired you, and what about more recently?

SW: My big influence in the last few years has been Meshuggah, the Swedish band. You know those guys?

MPc: They’re pretty heavy, aren’t they? (laughing)

SW: Very heavy, very heavy (laughing), but incredibly complex and incredibly rhythmically fascinating. They’ve been my real big influence over the last few years. You can definitely hear the influence on the last few records.

When I was growing up, what I really loved… I never really got interested in musicians and guitar players, but what I did get interested in was the producers – the kinds of people that had overall visions for a sound and a band, and they would be the guys that would sing, write, produce, mix. I’m thinking people like… Jeff Lynne from ELO, for example, was a big influence when I was growing up, Pete Townsend of The Who, Roger Waters of Pink Floyd, Brian Wilson of The Beach Boys… Those kind of guys were – and more recently Trent Reznor – those kind of guys have been a big influence on me because they’re not just guitar players, they’re not just songwriters, they’re not just producers. They’re everything. They’ve got this whole vision for a sound and a whole project and a whole kind of world that you can buy into, and I love that. That’s really how I’ve tried to model Porcupine Tree.