Almost forty years in the making, Marillion are one of England’s best kept secrets—not exactly a household name here in the United States, yet with sales of over fifteen million records and numerous Top 10 albums on the UK charts, they are bona fide rock stars who could pass through most of America with complete anonymity. But hanging out with the guys at New York City’s sold-out Playstation Theater, this is one American town in which the band is extremely well known.

Most music fans have no idea that Marillion pioneered crowd funding. Before there was a name for it, back in 1997, the band raised money directly from fans via the Internet to finance a North American tour. The success of this approach led to them crowd funding future music releases as well (and subsequently, artists across all genres began exploring the new financing model). The band left the big record label world behind and focused on releasing music on their own imprint. They have proved with each subsequent, fan-funded album release, that independent artists can indeed have successful and rewarding musical careers outside of the mainstream.

Of course, fans of melodic progressive rock know Marillion’s music extremely well—they are one of the most successful groups in the history of the genre, deftly weaving clever musical arrangements and sonic tapestries with though-provoking lyrical messages, all the while delivering the songs with beautiful vocal melodies that put todays auto-tuned pop minstrels to shame.

It was with great excitement that our ears were treated to the band’s eighteenth studio record, Fuck Everyone and Run (FEAR) in the fall of 2016. While some of the band’s post-Nineties work has met with less enthusiasm than other releases in the band’s expansive catalog, FEAR is one of the band’s finest outputs of the past decade, with an overall vibe that is more like classics Holidays in Eden and Brave, but delivered with the modern sheen of Marbles.

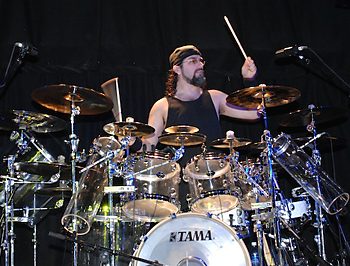

Marillion at the PlayStation Theater

“It’s got elements of, I suppose, of a classic Marillion way of writing,” explains guitarist Steve Rothery. “You can point to certain things in [songs] like, ‘The Leavers,’ and say, okay, that echoes parts of something you might have done in ’85. But that’s because we’re the same band, the same musicians, and we have the same creative processes.

But I think for eighteen albums in, I think it’s quite unusual for an album to be this consistent at this stage in an artist’s career. Most artists, after five or six albums, they kind of—I don’t know, they’ve lost whatever creative spark that they have. Not all artists, but a lot of them. Here we are eighteen albums in, so I think we can all be very proud of that.”

One of the great things about Marillion is that they never seek to release the same album twice. While there is a definite Marillion “sound,” they approach each record fresh, and create songs in the studio, collaboratively, through an extensive series of jam sessions and sonic experiments. Unlike bands in a more commercial musical genre, the band creates music that appeals to themselves, as opposed to writing what they think the market is looking for.

Says Rothery, “I think every album, we do try and do something different, and that’s one of the reasons that keeps it fresh for us, really. And really, we make music for ourselves. We make music that we enjoy and we hope that our audience will enjoy it, too. We don’t make our music for our audience, if that makes sense. I think that’s the only reason we can still enjoy the process, because we don’t feel restricted in any way about what is and what isn’t a Marillion idea.

Marillion at the PlayStation Theater

Keyboard player Mark Kelly embraces the freeform songwriting process (as does everyone in the group). “I think when you’ve been making music as long as we have, you need to have a certain random element, because it’s too easy to just go down the same well-trodden paths. You need things to throw you off those paths and put you into new territory. And the jamming process in itself helps with that, but also having new gear, new sounds, new things to try helps as well.”

Part of the success of Marillion is that everyone plays for the song instead of the spotlight. A great example of this surfaces when you talk with the guys about their favorite moments on the record, and they always point to other peoples’ performances. For keyboardist Mark Kelly, his favorite musical moment on the record is “The guitar solo in ‘El Dorado.’ I like the music that’s under it, and the solo that takes place, that’s a great moment for me.” And what of guitarist Steve Rothery’s favorite moment? “The very end section of ‘El Dorado’ I really love, because I just love Steve’s [Hogarth] lyrics in that section. I think it’s extremely evocative.”

Gear Talk

MPc: Now, let’s talk about some of the sounds on FEAR. Obviously, it sounds like classic Marillion. But, did each of you bring any of new toys to the party when you started this record?

SR: Yeah, there’s just maybe different… I used my GigRig G2 at the front end with some pedals—a [Waldorf] 2-Pole and the Pitchfork and various other pedals that maybe I hadn’t used on Marillion albums before. Some of the stuff I used in my solo album I kind of used, which I thought gave me a slightly wider vocabulary of sounds, I think, in certain cases.

Marillion at the PlayStation Theater

MPc: Are you still using Groove Tubes amps?

SR: Yeah. I love the Groove Tubes. I’ve also got this Pitcher Amplify Shadow SE, which is a bit Dumble-like. And sometimes I use those in combination for some heavy sounds.

MPc: I noticed recently, you have a signature guitar now, which I don’t recall from the last time we spoke.

SR: Yeah, this guy Jack Dent in North Carolina, Winston-Salem, makes guitars for me. He’s made about six. And that one—yeah, it’s special. They’re all amazing instruments. He chooses the very best woods and the very best electronics, and a he’s a real craftsman, so, yeah, great instruments.

MPc: Have you retired the Squire?

SR: No, no—well, I can’t retire the Squire because I need it for all the Marillion stuff up until Radiation, really, that was the main guitar. So that EMG SA [pickup] kind of sound, and the Kahler tremolo, especially. It’s a different way of playing that lends itself to, but yeah, for playing that stuff, there’s nothing else that can do it, really.

Marillion at the PlayStation Theater

MPc: What about you? What are some new updates in the keyboard rig?

MK: Well, I’ve moved over to this software-based instruments a few years ago and I haven’t really used many real instruments since then. The only notable exception is the Nord, which I use for organ sounds, really, just because I like the physical draw bars. And the sound of it is really nice.

But the sound of this album, really, if I have to choose one thing, it would be Omnisphere 2. It’s all over it. That, coupled with Valhalla Shimmer, the reverb plug-in—that’s all over this album. I use it, apart from, obviously, to the Zebra U-He synth and Diva, the two that U-He make.

And the other stuff, like the piano, it’s a physical modeling one rather than sampled.

MPc: Pianoteq?

MK: Pianoteq. It’s really nice. I really like it.

MPc: Yeah, we’ve been following that software since the very first iteration.

MK: Yeah, I didn’t like the early versions. So about version 3 or 4, then it started getting interesting for me and then when I heard version 5, I was like, wow, this is great. And I’ve been using it ever since, especially the Blüthner piano that they’ve modeled, is brilliant… And for electric piano I still use Lounge Lizard. And Minimonsta for sort of Moog-y, lead synth-y, sort of stuff.

MPc: Any of the Arturia stuff? The V-Collection?

MK: I prefer Minimonsta, the GForce one. It’s just more interesting to work with. And it sounds great. But Diva can have some monstrous, nice synth sounds. In fact, the bass pedal sounds, the Taurus pedal sound that Pete plays on stage, is coming from my Diva module.

Marillion at the PlayStation Theater

MPc: Do you find yourself constantly creating sounds?

MK: Yeah, I tend to go through sound banks. Some of them I buy from commercial sources and then I’ll just tweak them, layer them, do different things with them. There’s so many thousands of sounds available. Building sounds from scratch is—unless you enjoy doing it, just seems pointless, really. Because I’d rather start with something that sounds close to what I want or be inspired by a sound to play something. Like the sound that is the bulk of what makes up that big sound in “El Dorado,” the first big synth sound you hear came from Omnisphere 2, it’s called “Eye of God.” I don’t know who created it, but it’s great. And as soon as I heard it, I went, Wow, this is amazing. And that became the inspiration for that part, so that’s a good way to work.

MPc: Tell me about the sounds in “Wake Up in Music,”—the very sparkly, arpeggiated keyboard stuff.

MK: Well, it started off with a jam, with me playing a middle riff that went round and round. But then Mike Hunter chopped it up and made a loop out of it, a few bars of it, to make it sound more sequenced. And then he added—he added stuff. A lot of stuff that you hear in that, the way the music builds up in all different keyboard layers—quite a lot of that was Mike. It was a bit of a sort of—he did a bit, I did a bit, and then he did a load more and then I did a load more, and the band didn’t like what I did, so we ended using what Mike did. [laughs]

MPc: And then you had to learn how to play it!

MK: We haven’t played it yet, so I haven’t learned how to play it. [laughs] Yeah, it’s going to be tricky. But then we’ve done stuff like that. We’ve had that same sort of challenge with things like “Splintering Heart” or the beginning of…

SR: “Invisible Man.”

MK: “Invisible Man,” yeah, because it’s a layered keyboard: sequenced, loops and stuff. So we’ll just have to choose which parts we’re going to play and which parts are going to come out of the machines. And we’ll be playing to a click. We’re sort of used to that, really.

MPc: Well, Steve, some of your effects are quite familiar, like the Rotosphere?

SR: Yeah, the Hughes & Kettner Rotosphere. I love it. For me, it just sounds, it has so much more character than all the pedals that just emulate the whole process of it, because it doesn’t sound quite like a Leslie; it’s got its own character. Because it’s valve-driven, it adds a little bit of gnarly-ness to the sound that makes it just have more soul, to me. All those other Leslie simulators I’ve tried just don’t have that.

I also, I use some sounds similar to the Rotosphere. I’m using one of these actually, the Analog Man Mini Chorus, set to a very fast modulation rate. And that’s a great sound, because it doesn’t quite do the same thing as a Leslie. Slightly subtler. But it’s still a lot of atmosphere.

Marillion at the PlayStation Theater

MPc: Steve, you’ve got a pretty massive rig in general. What would you do if you had to pare it down to just the smallest possible set-up? what do you need to sound like you?

SR: Well, when we did our South American tour, we had to cut it down to a rig that you can fly with, so it’s still down to three shock-mounted flight cases. Stereo power amp, the [Groove Tubes] Trio, [TC Electronic] 2290, I think there was the [Lexicon] MPX G2. And then running the other system with pedals, with a Free The Tone delay pedal, which is like a 2290 in a box. Analog Man DS-1, and micro-chorus. That’s probably the main part of what I use, really.

MPc: Mark, what are you touring with in your keyboard rig this time around?

MK: Just a Mac Pro, maxed out on the memory, and just using Mainstage as the host VST controller. And then the Nord as a physical keyboard. The {roland] RD-just 800 is the main piano keyboard. And then the Korg Karma I still use.

MPc: I was going to ask, is the Karma still in the rig?

MK: Yeah, I still use a few of the sounds from it and they’re not really possible to create with anything else. Like, the big sound at the end of “Neverland” is a Korg Karma sound and it’s hard to try to create with [other synths]. I’m sure it could be done with more work, but… So I use it as a controller as well. And then there’s a Novation SL49 on the other side, as another controller.

MPc: At this point in your career, how do you guys come up with a set list for the tour?

SR: Yeah, we ask the American fans which songs they would like to hear. We have a spreadsheet with their favorite songs and we chose a lot of those. And then obviously, you play songs from the new album. We play three tracks from the new album. And a couple of old favorites. And we try and change three or four or five songs. If you’re playing cities that are geographically within a certain traveling distance, we’ll try and mix it up a bit.

MK: It’s hard. With eighteen albums, there’s always going to be stuff that people want to hear that we’re not playing, so—

SR: You usually change it a little bit, but not much.

MK: We’re playing over two hours, maybe two hour sand fifteen, last night, two twenty, depending. Some nights there’s been a curfew, you have to cut it short to two hours, but it’s okay.

All In the Family

Having their own studio makes it easy for Marillion to create records at their own pace—and without any outside influence, but equally impressive is that forty years later, the guys all live near enough to one another to make working on new music convenient, with the studio less than an hour’s drive from each of the band members. “It’s great having our own studio because it’s somewhere to go every day,” jokes Kelly, “Otherwise we’d just be sitting around getting drunk [laughs].” Rothery professes, “It’s a joy, still. We’re very lucky to have our own studio and to be able to do this for so many years as a career. We don’t take it for granted.”

With a lineup that has remained unchanged since 1989, Marillion are as much family as they are bandmates. Rothery opines, “Even if there’s a squabble and somebody throws their toys out of the pram, it’s usually forgotten about pretty quickly… And we’re all slightly eccentric, I suppose, in our different ways. We kind of cut each other some slack because of those eccentricities.” To which Kelly quickly injects with a laugh, “What you’re saying is, we’re a bit nuts.”