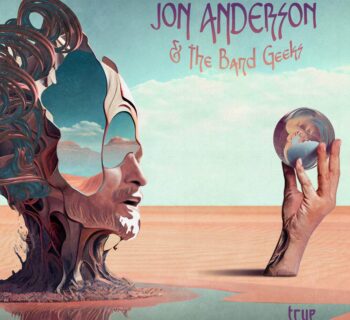

Jon Anderson hardly needs any introduction. For over three decades, Anderson was the voice of Yes, one of the most widely known and internationally acclaimed bands in the history of progressive rock. During that time, he’s had an on-again, off-again relationship with Yes, having been absent only from the 1980 album, Drama, and once again absent from the band on its 2011 release, Fly From Here.

Anderson has produced an enormous body of work not just within Yes. He’s amassed a a series of fourteen solo albums, seven collaborations with Vangelis, some Yes-related excursions such as the classic Anderson Bruford Wakeman Howe and the recent Anderson/Wakeman recording, The Living Tree, and also numerous contributions to projects from other musical artists.

Not one to slow down, Anderson has at least two more solo projects in the works as well as an acoustic tour with Yes keyboard legend, Rick Wakeman, set to resume in just a few months.

You might think that fame on the level of classic rock superstars would make the man unapproachable, but Anderson is just the opposite, a warm, grounded soul whose latest musical output is the result of collaboration with fans whom he solicited via his personal website.

We had a chance to catch up with Jon at his home on the California coast to talk about his 2010 release, Survival & Other Stories, as well as to reflect on all those Yes years.

You’re either in the group, or you’re not.

MPc: What was the motivation or theme behind the new release, Survival & Other Stories?

JA: I think the most important thing was that I haven’t released anything in about ten years. Over the last five years I’ve been writing a lot of music, working with people from around the world using the Internet as a basis of connection. People send me some music and I’ll sing some melodies and lyrics if the music is really connecting with me.

JA: I think the most important thing was that I haven’t released anything in about ten years. Over the last five years I’ve been writing a lot of music, working with people from around the world using the Internet as a basis of connection. People send me some music and I’ll sing some melodies and lyrics if the music is really connecting with me.

About five years ago I put an offer on my website asking people to send me music who were interested in working on different things rather than a commercial idea, more just the musical content. I got a lot of people to send me the music, and a lot of them were very talented so I started working with them. So I built up this really large scale musical studio, like a world studio. Now I work with different people on different projects all the time. It’s a very interesting experience. The album Survival is the first of three albums of this kind of music, where I’m working with people on a very spontaneous level.

MPc: So there’s more to follow, then?

JA: Yeah, I’ve been working on some songs today, and I’m working with my son on a couple of new songs. It’s very interesting to work with people… You know we’re all on the same planet. You used to have to be in the same room. Now you don’t need that.

MPc: Do you have a label behind this project?

JA: I have a label for this first album, called Voiceprint. I’ll be releasing other things through a company called TuneCore, which is a very good system for young musicians who want to get their music out there in all the different downloadable placed.

MPc: A few songs reminded me of the sound from one of your earlier solo works, In the City of Angels. What that your musical input, or just because fans of your previous work created new music in the style of your older work?

JA: I think obviously… they replied to my website so A: they know who I am, B: they know the kind of music I like doing, and when you put an album together you want to put as many variations on musical content as you can, unless it’s a very thematic idea. But this is just a series of songs, and like you say, some of the musicians were very into my music of the ‘80s, so they would send me music similar to that, or the ‘90s, or even the ‘70s. I did ask at one point for them to send me acoustic sort of, variations, on Yes themes, and things like that, so I have quite of a lot of acoustic music that I still haven’t produced yet, but it’s very classic Yes style of music. It’s very interesting to see how musicians relate to each other.

JA: Well, you know, we’re all very spiritual beings; I’m in that place where I like to sing about the search, the relative path that I take. It’s just a natural event – I think I started doing that when I started Yes, because “yes” is a very positive word, so my leanings were always into being very optimistic about life, and searching for that connection with the divine, and mother earth, and the god within, and I think that over the years I really discovered that. I’m writing about it in a more contented place because I actually know why I’m here, I know why we’re on this world, why we go through life, and I sing about it and enjoy singing about it.

MPc: What is your preferred writing style? Lyrics first, or do you sit with a guitar, or at the piano?

JA: All of the above really. Generally, music on the guitar you come up with a sort of melody, you tape it, put it on the cassette, and I’ll listen back to it and I’m trying to figure out what I’m singing about. So the lyrics are sort of hidden there. I’ll sort of map out the kind of lyrics that I was trying to sing and whenever I sing I tend to have a feeling in the back of my mind of what I want to sing about because of the music that I’m playing, or the music that I’m listening to. A lot of it is very spontaneous and I sort of sketch out the music and the lyrics in a very, very quick way. I don’t sort of labor the point too much, then I’ll go back to it a few days later and collect it or change it if I need to, then eventually over a period of two or three weeks you finish the song. I don’t do it like spend all day on a song. I spend a couple hours on the song and I move to something else. I’m very spontaneous with my work, and adventurous.

MPc: Your solo work features a lot of African and world music influences. Where does that come from?

JA: Well, when I was living in London, I would go to record stores and pick out records from Indonesia, Africa, all over the world, I was just very interested, in about 1969, 1970… I was very interested in world music and the power of the connection, that we’re all so musically connected in some way. So it’s always been part of my psyche, and sometimes I tried to put it into the group, Yes, but it was not always the best place to put it. So whenever I did any solo albums I’d always jump away from Yes music and try any kind of indigenous music, or Celtic music, or Central American music, or, you know, everything has to be different. Every time I did an album it really had to be very different from Yes. That’s why I was happy to work with Vangelis, because it was very different. It’s like that musical adventure is always in my heart.

When you’re working with a group, you have to listen to everybody.

MPc: It’s kind of ironic that within the context of a progressive rock band like Yes, you still had to go outside the band to pursue various other musical styles.

JA: There were times when I wanted to get the band to play reggae music. I had been to an incredible event in Trinidad, to the Carnival, this was back in 1977, and all I wanted to do was dance music, and they thought I was crazy. So you just say, ok, I’ll do it someplace else, with other people, when the time comes.

When you’re working with a group, you have to listen to everybody. You can’t really force anybody into a situation. With Yes, I was always very interested in structure, and the talent within the band enabled me to design some long form pieces of music before I actually went into the studio. I’d sort of hear it in my head and I’d go into the studio with ideas to create a long form piece of music and thankfully, everyone in the band was very excited to try to go into that direction. That’s why with Yes we created very long form pieces, which are still very valid in this day and age. They’re still very powerful pieces. It had nothing to do with radio or pop music. It was just musical ideas, and working on… indigenous music, it was part and parcel of the growth of Yes music. It was there, but it was very subtle.

MPc: With such a high and soft voice, I imagine capturing your vocals live has always proven to be something of a challenge.

JA: Not really. I think the adrenaline kicks in and all of a sudden I can sing very powerful, if I started singing now I’d probably break your microphone! (laughs) It really would. I talk very softly but when I start singing this other energy kicks in, and it’s pretty wild.

MPc: Do you now rely on in-ear monitoring?

JA: I went through that for about 10 years, but then I realized I was listening to great mixes in my head, on stage, but the mixes out in the audience were not as good as what I was hearing, so I started just using one so I could hear a lot better what was happening with the sound out in the PA. Eventually, now that I do my solo work, I don’t use in-ear monitors because it’s just me and the guitar. You don’t need that, and I don’t even like the big monitors in front of me. I move them to the side of the stage. I like to hear the all of the theater; it’s a lot different. You know when I do concerts with orchestras or any kind of large ensembles, I’ll just use one ear to get an idea of what everything is sounding like.

JA: I went through that for about 10 years, but then I realized I was listening to great mixes in my head, on stage, but the mixes out in the audience were not as good as what I was hearing, so I started just using one so I could hear a lot better what was happening with the sound out in the PA. Eventually, now that I do my solo work, I don’t use in-ear monitors because it’s just me and the guitar. You don’t need that, and I don’t even like the big monitors in front of me. I move them to the side of the stage. I like to hear the all of the theater; it’s a lot different. You know when I do concerts with orchestras or any kind of large ensembles, I’ll just use one ear to get an idea of what everything is sounding like.

MPc: Recently, you’ve done a lot of acoustic performances, such as with Rick Wakeman. Have you given any thought to doing an electric, full band tour, with music from your solo catalogue?

JA: Not really. If I did it, it would be a totally new piece of music. If I was going to do an ensemble, electric especially, I would jump into a whole new piece of music. I wouldn’t try to recreate my albums. I don’t think I would. I’ve actually been asked to do my first album, which is Olias of Sunhillow, and I’m thinking seriously about performing that sometime next year, or the year after. I’d like to perform it, I just have to get a group of musicians that understand it, and there is a group near Philadelphia interested in it, and they are working on it, so we’ll see what happens.

I have a friend in Paris, France that plays perfect keyboards for the Olias sound, so he’ll be part of the idea, but it’s a question of timing more than anything. But it does excite me to do the first album I ever did as a concert. Then, you know, if I have the musicians, maybe I’ll try songs from all my albums, you never know.

MPc: What kind of music do you tend to listen to on a fairly regular basis?

JA: I listen to the ‘40s and ‘50s channels on XM. You know, it’s when I grew up in the ‘40s and ‘50s as a kid, so I relate to that music very instantly, and then if I listen to anything else, I’ll sit down and listen to Sibelius, the Finnish composer, or Stravinsky.

MPc: The band, Yes, has had a revolving door of members throughout the decades, with Chris Squire being the only constant on every album. What is it about this band that fosters so much continual change?

JA: It’s very, very simple. You know some people, you have a band that comes from Boston, or comes from Santa Fe, or Liverpool, or Newcastle, they always stay together in general, they’re from the same town. Whereas Yes, we built with musicians that are scattered from all over different parts of southern England, so the concept is that you’re in the band, working for the band, connected to the band through music, and if for some reason you don’t feel strong enough to be there at the rehearsal, or strong enough to be there emotionally on tour, connected, then in a way you’re not part of the band, you’ve decided to be, I don’t know, disconnected from the band.

So, when that thing happens, it’s always a decision within the group, the democracy within a group will say “Okay, the guy’s not really into the band at the moment. We’ll try to talk to him and if he’s not interested, or too busy being a rock star, or whatever, maybe it’s time to change for someone more interested in pushing the music further,” and that’s a normal situation I think.

It became a more published thing about who is in the band, and who isn’t, but inside of the group it was always about the music and the commitment to making music. I think people do forget that, that it was all down to where the music can go, and who will be excited to perform it, excited to be at rehearsal, to commit themselves to work on modern music. From a publicity point, it was always like “Oh, people are changing in the band, it must be hard to be in the group.” No. You’re either in the group, or you’re not. You’re either emotionally committed or you’re not, and that was always my commitment to the success, because if you get success within a group, A: be very thankful B: ‘Gotta work hard C: don’t give up on the path you’ve taken, don’t become sort of, you know (laughs), what’s the word, enamored by success, you become a celebrity. Keep your feet on the ground and be thankful for what you’ve been given — that was always my thinking. That’s probably why I’m still creating music and I still have a viable voice out there musically, as well as people like my voice as a singer, but I’m also very interested in pushing the envelope a little.

MPc: The Rabin-era years of Yes meet with extremely polar reactions from fans of the band, either loving the direction or hating it. When you look back on the various chapters of Yes, how do you feel about 90125, Big Generator, and Talk?

MPc: The Rabin-era years of Yes meet with extremely polar reactions from fans of the band, either loving the direction or hating it. When you look back on the various chapters of Yes, how do you feel about 90125, Big Generator, and Talk?

JA: Well, I think that 90125 was a classic album on any level, by any band, it was a musical journey, an incredible production, and I joined that process three quarters of the way in. I went in towards the middle-end of the actual creation of that album, so I listened to it and went “Wow, this is a really good album. I want to be part of it. Yes, I’ll join the group, I’ll sing the parts, I’ll write some lyrics, I’ll sing a chorus here, and write a chorus there, and I’ll sing ‘Owner of a Lonely Heart.’” It was a very commercial song, and I realized that was the point of the project, to create a very commercially based album, and that’s what it was, and I went into it fully understanding that.

The danger was Big Generator was chasing that dream again, chasing that crazy hit record. It never happens if you chase it — it should come very naturally. Whereas Talk was a very beautiful album, and I spent a lot of time with Trevor writing a lot of that music from the ground upwards, whereas Big Generator I was kept out of the loop for six months, so I went and made an album with Vangelis — because that’s what you do. But Talk was really one of my favorite albums.

There were a lot of people saying it’s not Yes, it’s not the real Yes… of course it wasn’t. It was a different kind of Yes, a different version of Yes, but I still had a deep belief in it and I still wanted to try to stretch the musicality of the band after 90125, but, it wasn’t meant to be. But Talk has some really beautiful ingredients, there are two or three songs on there that I’d love to sing again, so that was it.

MPc: It was interesting — on Talk, the sound, even of what Trevor was writing musically, had more of a “classic” Yes vibe to it than on the other music he had written with the band up to that point.

JA: That’s because he allowed me into his world musically, and I was able to influence him a little bit about what the true essence of Yes was all about, musically speaking. So Talk was an album that was really able to express, as you say, an earlier energy of Yes. And that’s what I bring to the table.

The last Yes album that we recorded was Magnification. It’s still, I think, one of the really great, really powerful Yes albums. We didn’t give up on the progression of Yes. Two really strong pieces that came out of that period were “That, That Is” and “Mind Drive” [from Keys to Ascension 1 and 2] which are very long form pieces of music, and I was able to again influence the band, push them in that direction and say “Come on, let’s try this,” because people are willing to listen to that kind of music, and they’re willing to see it happen on stage, and I don’t think we should let go of that kind of adventure in music.

MPc: Could you see yourself working with Trevor Rabin again?

JA: He started writing film scores — he’s done, I think, 40 scores for movies. The guy is amazing, and I’ve seen him over the last few years. I’ve popped down to see him once or twice a year, just to hang and watch him create, and it’s really beautiful to see. He’s a very open hearted, talented guy, he’s a sweet guy, and we actually started writing some ideas, so we’ll see what happens next year or the year after.

I’m still a Yes fan. I love what we’ve done. I’m so proud of the music we’ve created.”

MPc: The album, Union, really drives home the point that there are enough players in the various Yes lineups to create multiple bands. Was the decision to produce one album and tour from everyone a label decision or a band decision?

JA: Well, the tour was amazing. I think that was the only reason I wanted to do that, to bring it all together and see what it was like on stage. In my heart, I think that creating music always has to do with going on stage and performing it rather than, you know, you make a good record (and that’s really very important), but then you have to bring it on stage and that’s the key, to be on stage and recreate that, and develop it as well. So, to be on stage with all the guys and we’d finished that whole show with “Awaken,” which is one of my favorite Yes pieces of music, I was in heaven.

JA: Well, the tour was amazing. I think that was the only reason I wanted to do that, to bring it all together and see what it was like on stage. In my heart, I think that creating music always has to do with going on stage and performing it rather than, you know, you make a good record (and that’s really very important), but then you have to bring it on stage and that’s the key, to be on stage and recreate that, and develop it as well. So, to be on stage with all the guys and we’d finished that whole show with “Awaken,” which is one of my favorite Yes pieces of music, I was in heaven.

The album was stuck together with superglue, a little bit. It’s not an album that I listen to, it’s just an album that was put together simply because I thought it would be really good to try and get it on stage and perform with everyone in the band. I already had a great experience doing Anderson Bruford Wakeman Howe, and the second of that idea could never really happen because a couple of the guys just didn’t want to do it that way, so eventually it got a little bit of confusion around it, and the music wasn’t driving the whole ship, if you like. So when Chris got in touch with me and said, “Hey let’s get together and make an album of all our music things,” I said “Why not!,” but in the back of my mind all I was thinking was, Wait till we get this on stage, this will be wild. (laughs) Rick Wakeman always says the same thing: he didn’t call it Union, he called it Onion because every time he listens to it, he cries. (laughs)

MPc: And of course this past year, they finally released the Union concert on DVD.

JA: Yeah. I’ve never seen it… but I was there (laughing). I went through so many emotions on that tour. It was such an incredible experience.

MPc: The latest Yes album, Fly From Here, is pretty good, but sounds more like an Asia album than a Yes release given the current band lineup. From what we’ve seen and heard coming out of the Yes camp, it seems like Benoît David is going to be the band’s lead vocalist moving forward. Where do you see your relationship with the band going in the future? Or will you just be focusing on your solo efforts?

JA: Well, I suppose the quick answer is that I’m sure, possibly, we’ll get together again… I joke and say, “When they wake up” (laughs). But it’s as though they all have a path they need to go along, and we’ll just see what happens. Like you, I listened to a couple of tracks and thought this is not my idea of Yes, but in some ways you have to say this is the way it has to be.

I feel a little bit sad for the fans, of course, who just want Yes to be Yes to be Yes. I wanted the Beatles to be the Beatles forever, but they packed up and changed, and life moves on. So in some ways, it will happen when it happens. That’s my new mantra.

MPc: So what’s next for you?

JA: Well I’m doing a lot of writing, finishing up a large-scale piece of music that I love. I’ve got two in the works; this is the first of the ideas. I’m hoping to release it for the winter, for all the Yes fans out there. In my heart, I’m still a Yes fan. I love what we’ve done. I’m so proud of the music we’ve created. It will always be part of my life experience.

MPc: What is it, do you think, that makes Yes music so enduring through generations of listeners?

JA: It’s very honest music. It wasn’t great all the time, but some of it is really, really good, and it was done with the right intentions. It was done for the love of music, and the adventure of music. I never think of Yes as a prog rock band — a lot of people do. Musically, it was an adventure to be in Yes. When we could play songs from the ‘70s in the ‘90s, 25 years later, in 2001 and 2003 and 2004, playing “Gates of Delirium” or parts of Topographic or “Awaken”… when you can play that music 25 years later and still have an incredible feeling about creating and performing it… and it’s very different from the norm. That’s the whole point. The music is so different. There isn’t anything like it. That’s why you have Yes fans. They’re committed to it, just as I was to creating it. There’s something very magical, or mystical about it.