The British progressive rock band, Porcupine Tree, is no stranger to the readers of MusicPlayers.com. As one of the preeminent (and Grammy nominated) prog bands in the world, every member of this group is recognized for their outstanding musicianship, and we’ve had the privilege of speaking with many of these guys previously.

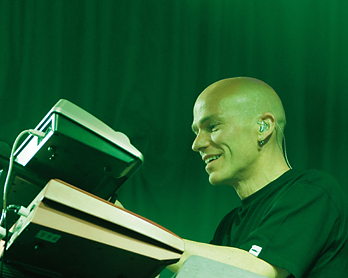

Until this past fall, though, we hadn’t had time for a lengthy sit-down with Colin Edwin, the Australian-born bassist who has been an essential part of the band’s sound and style since 1993.

A few hours before the band’s first-ever show at New York City’s famous Radio City Music Hall, we spent some time with Colin trying to sneak into the Rockette’s dressing room… I mean, talking about his playing, his style, his influences, the gear, and that kind of fun stuff, of course.

When you’re doing what you should do, most of the time people don’t really even know what you’re doing.

MPc: You were once quoted as saying, “Bass is not an instrument you play to get noticed.” So what motivates you to play bass?

CE: There’s a funny thing about the role of the bass that a lot of bass players don’t get. And when I first started playing, I was always playing in my friends’ bands with quite a lot of people. The thing I used to hear a lot of was “So-and-so (who I was replacing) was a great soloist.” And I used to think, “That’s like 2% of the show.”

A lot of people feel that “holding it down” is beneath them. It’s a funny sort of thing, the bass. Because when you stop or make a mistake, it’s really obvious. But when you’re doing what you should do, most of the time people don’t really even know what you’re doing. I’m not talking about musicians; I’m talking about listeners. [laughs] They don’t really know what it does.

It’s funny, we had a rehearsal years ago, I remember we were rehearsing for a tour over a week or so and I had to miss one day because I was moving house that day. And I came in the following day and said to the other guys, “How did you get on?” and they said, “We had to stop after about ten minutes because it sounded like a drum solo and a guitar solo, like a mess.” [laughs] And the funny thing about the bass is that you can do something very simple that’s very powerful because it’s pulling everything together, and I’ve always been quite happy to play that role. I don’t really think that, a lot of the time, when you do more, and this is not the case for every band or every star in music.

But most of the situations I’ve found myself in, when you do too much, when you overplay, you’re sort of taking away from what’s going on in a funny sort of way, or you’re not supporting the rest of what’s going on. It’s a funny thing. Another quote I heard from a famous double bass player, Danny Thompson: “The bass is an instrument of judgment as much as anything else.” And I’ve always valued that information. That’s very true, so that’s kind of what I mean by not being noticed. You’re being the background but you’re still playing an important role. I think Guy Pratt said something about how it’s like being a waiter — when your waiter is doing his job properly you don’t notice him [laughs] but when he drops your plate on the floor and spills your drink, then you’re noticing him for the wrong reasons. And I think on the bass that’s when you get noticed: when you make a huge mistake or when your amp stops and the whole bottom end goes.

MPc: You play four-string basses primarily and sometimes tune down as low as C, F, Bb, Eb. Why not just play a five or six string bass?

CE: I have thought about that. I have a five string fretless that I use at home, but I’ve always really enjoyed playing a four-string and I’ve never felt the need, until Steven [Wilson, Porcupine Tree singer/guitarist] started down-tuning, and that’s the same time I got this low-tuned Spector that you’re talking about with that tuning. I never really felt the need to go lower than a D. And I’ve always felt a bit uncomfortable playing some of the five-strings with the string spacing a bit closer together. If you think about it, there are only three low notes you’re not getting. You’re not getting B, C, and C#. I can comfortably get to D on my four-string. And I didn’t feel that there’s a trade-off between the low notes and the extra weight, and I’m not particularly tall or anything (laughs) so the extra weight and the extra size of the fret board, I never really felt comfortable with any of the ones I’ve tried so far. I might change my opinion, but I don’t ever find myself thinking, “Oh, I need a lower note.” And I’m also a fan of octave pedals, so I’m quite happy to use an octave pedal if I need to go low.

And as for going up the other end of the bass, going higher, I don’t really find myself having a call for that or playing that kind of chording style that six-string players do. I think that comes from playing in Porcupine Tree for such a long time, it’s very sonically dense. I ‘m actually quite aware of going above the first five frets a lot of the time or playing quite high. It’s something that in an ensemble, you have to be very careful that the bottom end would disappear.

MPc: You’re competing with a lot down there, with the detuned guitars, many layers of guitars, and Richard’s synthesizers.

CE: That’s right. There’s a lot of keyboard things going on as well. I think I’ve got a space most of the time that I like to be in sonically, and it doesn’t always work stepping outside of that for me.

MPc: Do you tailor your EQ to give you a little more presence in a certain range that you might not ordinarily be heard in?

CE: Not really. It’s more to do with just having an awareness of what everybody else is doing and listening to what else is going on. There’s been a couple of occasions when I’ve been recording and I thought, “That would be a great place to put a fill in,” and I’ve tried it, and it hasn’t worked.” So I don’t know, I have experimented with a five-string, I haven’t played a six-string, I haven’t really felt comfortable with it for those reasons.

“It’s all about doing what’s right for the tune.”

MPc: You mentioned octave pedals, and obviously your pedal board has a lot of pedals, so clearly you’re a guy who likes to add effects to bass.

CE: Yeah, I tend to use them like salt and pepper. [laughs] Put bits here and there. I don’t do this Bootsy Collins full-on effect thing, something like… Doug Wimbish uses tons of effects. I love Doug Wimbish, but I tend to use them when they’re more or less kind of a surprise, with the exception of maybe an overdriven tone that I might use through most of a song, or I’ve started experimenting with envelope filters or a Phaser pedal that I used to use years ago.

But I’ve always found that little bits of effects — for a long time I avoided them, I used to think that it was sort of “cheating” in some way or they kind of sucked your tone away — I found that I like to use them at certain times rather than most of the time.

MPc: So who’s doing the low synth-like effect during “Halo?” Is that you?

CE: No, that’s the synthesizer. There’s a bass guitar line that’s pretty straight. The bass guitar, there’s no effects on that so you’re hearing Richard. I’m using an EBS IQ pedal for a couple things. And I think when people hear it they think it’s Richard. [laughs] But no, it’s bass guitar. That’s something quite new for me. I mean, envelope filters are normally associated with funk bands and stuff, but I quite like that sort of stuff and it’s a fun place to use it.

MPc: I guess you have to keep track of a couple basses and make sure you have the right one in your hand for the right song.

CE: [laughs] Yeah, for sure! On this tour, I’ve been using mostly a Wal four-string, and also a Wal fretless I used to play exclusively with Porcupine Tree. Up until about seven or eight years ago I didn’t play anything other than the Wal fretless.

MPc: Around Lightbulb Sun, was that still fretless?

CE: Yeah, pre-that as well, from the early days of the band. We’re actually doing a lot of that album on tour. But no, I just used to play that bass all the time and the fretted one occasionally, but there’s something about an instrument when… I mean, I’ve got loads of different basses… but for years and years I had the Wal, and I started with a fretted one, which was the first decent bass I could afford. And at the end of the Eighties you could pick them up for a lot less than you can pick them up now.

A lot of them became hip for a while and people had them, and all things that are hip become un-hip, and that was the point I got mine. We could pick them up for about 400 English pounds, which is about $700, and now they go for $1,000. But they’re really well-made, they’re very reliable, but even more than that, for me, I didn’t play them for a while, but a friend of a friend was selling one and he rang me up and said, “I’ve got this Wal bass and I want to sell it and I know you’ve got one and I think it’s worth about 1,200 quid ,what do you think?” And I said, “Well, if you want 1,200 quid for it, I’ll have it if it’s any good,” and I knew I could sell it for more.

A lot of them became hip for a while and people had them, and all things that are hip become un-hip, and that was the point I got mine. We could pick them up for about 400 English pounds, which is about $700, and now they go for $1,000. But they’re really well-made, they’re very reliable, but even more than that, for me, I didn’t play them for a while, but a friend of a friend was selling one and he rang me up and said, “I’ve got this Wal bass and I want to sell it and I know you’ve got one and I think it’s worth about 1,200 quid ,what do you think?” And I said, “Well, if you want 1,200 quid for it, I’ll have it if it’s any good,” and I knew I could sell it for more.

I went by his house and tried it out, and I said, “Great, this is lovely, I”ll have it” but I said, “I’ll be honest with you. If you want to put this on eBay you’ll get another 500 quid for it at least.” And he said, “No I just want to sell it for 12.” And I said, “Great, I’ll have it!” And the funny thing is I hadn’t played my Wal for a while. It’s one of those things that when you play something for a long time, it’s almost like a limb. And I felt very comfortable with it as soon as I picked it up. When we started to do The Incident, we had a group jam session and I took it along because I just bought it off this guy and it felt great playing with the band. So I ended up kind of going back to it.

I’ve been a bit reluctant to use my Wal on tour because they shut down for a while and started up again. I always had this fear that if anything happened to it I could never get it replaced. Equipment gets terribly mashed up on tour, people don’t look after things, things get broken, things get lost, and it’s kind of irreplaceable. And it’s not just the money. It’s the fact that I couldn’t get another one without trolling around secondhand places. So I kind of went back to it, it just sounded right for the material we were working on.

But that's the thing about guitars, I think guitar players and bass players have a bit more of a thing than just playing it. You feel like you want to play that instrument sometimes. For me I was just playing that instrument for so long, and something better might come along, but I feel I might be able to express myself more on that. I’ve got a certain relationship I have with it that I won’t have with anything else. It’s not to say that anything else is bad, it’s just to say that I’ve got years and years of playing that particular thing that I’ve worn the varnish off. I kind of feel that when I play it and it’s more personal. It has a lot more power for me, that fretless bass. So no disrespect to anything I’ve tried since, or that I might play anyway, but that’s definitely the desert island bass.

MPc: Certain things about playing a new instrument inspire you to play differently.

CE: It’s something unquantifiable. You can’t read about that in a review, because that’s your relationship with that instrument. And it’s not about the EQ and the tech specs and that kind of stuff. On this tour I’ve got the two Wals, the fretted and the fretless, and I’ve got the Spector which I down-tune, so that’s the one that’s tuned C, F, Bb, Eb.

MPc: That one has a different neck scale length.

CE: That’s right, it’s the 35-inch scale. The model is the Euro 435 LX, so it’s a slightly longer neck. And I found something that was kind of a happy accident, around the time when Steve was experimenting with playing Drop C on the guitar. I have had a relationship with Spector, and I have been using their basses, and they said they wanted to give me a model. They kept suggesting a couple of things, but I read through their catalogue and the one that appealed to me was this 35-inch scale. And I was thinking about the low tuning. So I had it set up specifically as the bottom four of the five-string. I was very happy with that, because for the heavier moments it works really well, I think. To be thinking about the bottom, and most of the time you just need that bottom end, kind of heavy thing going on. So it works perfectly for me.

“You have the budget, but it's like you're spending $100,000

to make something ten percent better.”

MPc: Steven is known for writing the majority of Porcupine Tree’s music. He also brings his demos to the band. How much detail does he put into bass lines on the demos vs. how much space does he give you guys to create parts?

CE: Sometimes he comes up with something completely open, and refers to it as a guideline: “Do your thing here,” you know. And sometimes he has a very specific idea. It depends on the song. But most of the time one of us gets to do our thing around the framework. There have been times when he’s said, “Look, I really want this and nothing else,” I mean, he has some great ideas for lines sometimes. I’m always open for some of the things that he might have that he wants down. There’s a couple of bass lines that he’s come up with that have been really good. It’s all about doing what’s right for the tune.

Sometimes we have a lot of freedom between us and sometimes we don’t discuss anything. When we’d done the group sessions for The Incident album, the second disc, a lot of that we kept the original stuff, basically jams. So there’s a few bass parts on there, a few of the songs it was literally the first or second time we might have played them. I ended up going to the studio, doing a lot of different things, and it wound up on the record when I did it in ten minutes, which is good because it means my judgment was right the first time. I don’t mind doing things over and over again when it’s right.

MPc: Do you have a typical approach to how you record your bass in the studio? Straight to the board? Miked?

CE: I’ve tried various things over the years. A lot of the time it’s straight into the board. What I’ve started doing now, and what I tend to do a lot of the time is I have the EBS little DI thing [MicroBass II] and it’s a fantastic little box. You can split the signal, do all sorts of things. And I always record direct through that and then I run a line to a [line 6] Pod. And I have an amp simulation on the Pod that I like. I’ll record two signals and then I’ll blend them how I want them.

I also like to do that with effects. If I’m using effects, I like to have one clean signal and one effected signal. One problem with effects is that the bottom end drops out. And I’ve found that there’s nothing worse than you get to the heavy part of the songs and you put your distortion pedal On and the bottom end goes out. And one of the other great things about the Wal bass is they have an XLR out. So you can have a totally clean signal. You can even record multiple tracks and try different effects. But I normally find with effects, especially things like envelope filters, distortion, not so much with modulation effects… on many of those things I like to have it clean [on one track] and blend it in. That gives you a lot of flexibility in the mix as well.

MPc: Are your EBS amps solid state or tube?

CE: They’re both. So yeah they have a tube as well — the EBS TD650s.

MPc: Do you have a preference for how you dial in your sound?

CE: Well I use the tube circuit as well. They’re something I’ve always liked the sound of. I tend to find with amps that I’ll fiddle with them when I first get them and then I tend to leave them, and the settings don’t change. There’s so many things in your chain when you’re playing, but the most important one is your fingers more than anything else, and that really makes a big difference to me. So once I'm happy with the sound on the amp, I'll tend to mess with the guitar or with where I play or how I play more than anything else. I tend to go for a basic sound. They're quite flexible, though, those amps. You can get all sorts of tones with them. But once I've got the sound I like, I tend to (kind of) leave it.

MPc: I notice the box of in-ear monitors over there. Westone?

CE: Oh, no. These are Sensaphonics. These are quite unusual because you have an ambient element that you can dial in. So there’s a microphone's in the mold. And I'd been using very cheap molds for years, and in fact, it was Gavin [Harrison, drummer] who turned me on to these. He's tried all sorts of things, and he said they were the… we actually both got them at the same time, but he read up on them. And he had the same kind of problem.

One of the things about playing the bass is that what's enjoyable about it, when you're playing live, is the feeling of the air and the kind of presence of the speakers and all that kind of stuff. And when you have your molds in, so much of that goes. But I really like the idea of molds because they save your hearing. I never get ringing ears anymore, and all those kind of high frequencies, like the cymbals and things, are no longer destroying my hearing.

But I was kind of feeling sometimes that it's almost like you're going to your own gig, and you're listening to it through a letterbox, you know? [laughs] It's like watching a film through somebody else's letterbox. You feel like you're not there because you're not hearing all the sort of ambient sounds and the audience and the rest of it.

So these have a pack with a little switch, and you can have a full ambient mode with your mix, and you can turn the full ambient off and dial in a certain amount of ambiance into what your mix is. And that's kind of the best of both worlds. So I've been really, really happy with those since I got them.

I'd recommend them to anybody, especially (I guess) people who play drums and bass and anything where that kind of thing is more important, to have that kind of presence, you know.

Four Man Acoustical Jam: Porcupine Tree Unplugged

Four-Man Acoustical Jam. Porcupine Tree unplugged, more or less...

“You don't want to be a copy of somebody else.”

MPc: Now moving on to one of our reader favorites — the “first story” part of our interview. I'd love it if you could tell me the first story that comes to your mind when I dig up some earlier Porcupine Tree recordings.

CE: [laughs]

MPc: Related to your experience tracking, writing, or the gear you were using at the time. Some event that you recall. Let’s start with Lightbulb Sun.

CE: Lightbulb Sun… Lightbulb Sun. [laughs] It was so long ago, I don't remember anything! Well, some of that was done I'm sure at Foel Studios in Wales, and some of that was done, I remember, recording at Steven's place. I remember using my Wal fretless quite a lot for that album. And I was experimenting with some instruments I picked up on my travels. [laughs] I'd been to North Africa for a while, and I had this thing called a gimbri, which is a three-string bass instrument that they play. And there's a little bit of that in the middle of "Russia On Ice." There's a thing that sounds like a rubber band [laughs], and that's me playing the gimbri. And I also had — I'd been to Turkey, and I picked up a thing called a saz, which is a sort of Turkish lute with a very long neck. And I'd been messing around with that, and that ended up being on "Hatesong," which has been a live favorite for years. We still play that one live.

MPc: Yes! [I never miss their shows in the NYC area…]

CE: It's one we wheel out for festivals because there's a moment where people who don't know us, that's the tune that will kind of often [laughs] drag them in, you know? There's a sort of change in the atmosphere. There's often tunes like that where it really gets the audience going. That one works really well live.

That [record] was reissued recently, and I hadn't listened to it for years, and I put it on and I still enjoy it. It's an interesting album. It's got a bit of everything. It sounds quite “of its time” because the music changed after that.

MPc: Sure. Now you need to tell me about something from In Absentia.

CE: In Absentia, well, that was our first big, major-label thing. We all came and recorded it in New York. And of course, it was Gavin's first recording with us [He replaced original drummer Chris Maitland]. So it was a transition time. The material was all written, and in fact, we'd rehearsed a lot of it with Chris. And it didn't work out with Chris, so we had the position where we knew we were going to go to New York and record, and we didn't have a drummer, and we had to get somebody really quickly.

And we knew… Richard and myself knew Gavin through different things. Richard and Gavin had worked together. And I knew Gavin through a mutual friend of ours who's a bass player. He's a guy who kind of taught me a lot as well. So I'd known Gavin for a long time, and I knew he had a great reputation as a really good player. We just got together with him, and we had a bit of a play-up, and I never had any doubts that he was going to fulfill that role and be able to play the material. But I think from his point of view, it was probably quite difficult because he walked into something [laughs] and we didn't know if he was going to be [our new] drummer. He was just going to play on the album. But he ended up being so right for the stuff that he ended up being in the band.

But it was quite exciting because we were coming here [to New York]. We were recording at Avatar Studios, and we had a budget to do stuff. And it was a big departure from going to Wales and playing in a little place with no money [laughs] and, you know, we can't do this or we can't do that, or we've got to save the money for this or, you know. So we had the opportunity to have that studio time. Everything came together really well.

I think it's one of the strongest albums. I really like that record. I'm really happy about the way it [came out]. It was a happy time for me. [laughs]

MPc: And how about Deadwing? What do you remember?

CE: Well, Deadwing, it seems there were a lot of problems with that because there were times where we were touring a lot, and we weren't always doing so well in every territory. So it felt like a bit of a struggle. And there was a business reason why — and I can't really remember… the album was done, and it didn't come out for eighteen months or something. There was a long time where we didn't really do very much. And that was one where we didn't go to a big studio. [laughs] It was kind of the opposite way around.

Now we're all a bit more confident about recording I think the difference with a big studio is it does make a big difference. And of course, you have the budget, but it's like you're spending $100,000 to make something ten percent better. You understand?

MPc: Yes.

CE: And that ten percent not everybody can hear. And it's cumulative, anyway. So if you go to a really expensive studio and you have a really expensive master engineer and all those kind of things, then you end up with a better product. But to get to that stage, you've got to go through so many different things. And you can get a very good result without doing that, without doing any of that, especially with the way technology is now.

But it's all been a learning curve, the whole thing. It's good to know that when you do an album, you listen to it and you think, "Yeah, it sounds better than the last one," and that means you're going in the right direction. [laughs] And I've always felt that about everything we've done. Everything sounds better than the last one. There's always things we've tried. Gavin might have gone to a different place to do his drums, or he's learned something at home if he does his drums at home. He's picked up something from an engineer he's worked with. I picked up things from working with Paul Northfield when we did the In Absentia album. Some of the things I would never have done, left to my own devices. The thing I was telling you about having two signals, the idea of having one that sounds really fuzzy and distorted, and just dialing a little bit of that in with your clean sounds. On its own, it sounds dreadful. [laughs]

MPc: What do you do live? Do you run your effects in a wet/dry setup?

CE: No. It's all coming off the one thing. The sound guy, I think, changes what he does, but I'm sure that what he has in my DI for the bass, most of the time. I go through a DI box, and he blends that with what's coming off my amp. I think he gets a good sound live.

MPc: What do you remember from the making of Fear of a Blank Planet?

CE: Fear of a Blank Planet was… I recorded that — all the bass parts, at my place.

MPc: That's a different approach again.

CE: Yeah. Well, I've done that with some of The Incident as well. But yeah, I did most of that at home. And it was kind of weird because these days, we're always tracking. We're always playing separately. One of the things I enjoyed about The Incident was when we all got together and played [live]. And I think Gavin redid his drums for some of it. But there's still a certain vibe that we get. I would like to possibly do that next time — actually record together. And it's going to be like going back in time because everybody does everything separately. But we did a BBC session after Fear of a Blank Planet came out, and I thought it sounded better than the album, and that was all done in one day.

There were some great things about Fear of a Blank Planet. The best thing was that we road tested the material, so everybody knew what they wanted to do. And what had happened with a lot of the previous stuff is you record it and then you go out and play it for a couple of years, and you think, "We're playing it better now than we did on the record." And the record's the thing that's going to live on. The live performance has been and gone.

So we road tested the material, and it's more — especially for myself and (I know) for Gavin — it's more about playing the things [live] to try different things that work, and you have an empathy with the material because you've played it in front of an audience. So I think that approach and the approach of playing together, it's kind of like the '70s. [laughs] That's how people did it in the '70s. I'd like to have that approach again.

MPc: Do all of you guys basically live in the same general area in England these days?

CE: Pretty much, yeah, around London.

MPc: So you guys can easily get together to jam.

CE: Oh, yeah. Myself, Steve, and Gavin all live very, very near, ten-, twenty-minute drive of each other. Richard lives in South London, which is a bit of a trek. [laughs] But it's not so much. The thing about the jams is you don't want to all come together and just have a jam and leave for half an hour. It's about coming to the… we always come with things we've worked on, like a basic idea, like a chord sequence or a bass line or a groove or a drum pattern or something that we can build on, so we're not just starting from scratch. Otherwise, it ends up just being a sort of ridiculous [laughs] waste of time. But that was very constructive last time we did it, so I hope we can do that again.

MPc: Cool. Do you think there is anything else I didn't cover that you might want to talk about here?

CE: I’m always surprised by the sort of questions people ask. They often ask things that I'd never thought of. [laughs]

"I don't want to listen to that. There's a hippie on the front."

MPc: Actually, something I don't know too much about… Who were some of your early influences?

CE: Well, I suppose the first music I was really exposed to was sort of the late '70s stuff. I've got older sisters, and when I was younger, they were always playing things like the Chic records and Sister Sledge records, disco stuff. I love all that still, to this day. I never get bored of listening to Bernard Edwards. The Police albums, the first couple of Police albums, were big spinners, as was The Stranglers' stuff. So that's kind of part of your makeup, the music you first hear, isn't it?

And then when I developed my own taste, I first of all got into a lot of the late punk stuff. Killing Joke and Joy Division and stuff like that, and it was kind of what I latched on to. And then my older brother actually plays classical guitar to quite high standards, and he was a fan of… there's an English folk guitarist who's dead now, John Martyn. Beautiful songwriter as well. And my brother left behind a John Martyn album when he left home — we shared a room — and I remember putting it on. It was in the corner of this room, and there's this hippie on the front, and I thought, "I don't want to listen to that. There's a hippie on the front." And I put it on one day just to hear what it was like, and it was an instant thing. I thought, "This is beautiful." It's beautiful acoustic guitar. Double bass. Great songs. It's an album called Bless the Weather. And that got me interested in playing double bass as well.

And then, I got into more jazzy things. I got into Joni Mitchell. And I think it's the case with anyone. If you're interested in something, you follow a path. You learn more about things. And then, I think I'm quite open-minded. I think we all are. Most musicians don't just want to listen to one thing. [laughs]

MPc: Well, not a lot of prog rock bass players play fretless as a primary instrument in rock songs.

CE: Yeah. Well, I always enjoyed the fretless. I liked, and was a fan of — Richard [Barbieri, keyboards] was in Japan, and I was a big Mick Karn [bassist, Japan] fan. And at that time, in the early '80s, there was a lot of prominent bass on records. Pino Palladino played on those Gary Numan records. And I heard Jaco, of course. I got turned onto Jaco Pastorius. And I always liked the sound of the fretless. I liked the kind of thick sound.

CE: Yeah. Well, I always enjoyed the fretless. I liked, and was a fan of — Richard [Barbieri, keyboards] was in Japan, and I was a big Mick Karn [bassist, Japan] fan. And at that time, in the early '80s, there was a lot of prominent bass on records. Pino Palladino played on those Gary Numan records. And I heard Jaco, of course. I got turned onto Jaco Pastorius. And I always liked the sound of the fretless. I liked the kind of thick sound.

It was a bit of an anathema to me to use a pick and play with a rattly sound, which is your typical rock thing. But I was dragged into that one. [laughs] I mean, now I enjoy it. But that was the first kind of thing that I was drawn to, I guess, and then it sort of grew from there.

I guess I'm not alone. When you get older, your influences are less directly musical, and they're more about your personality. Ultimately, I think that what you're really hearing is somebody's personality coming out in the instrument. And that's what you want. You don't want to be a copy of somebody else, and you've got to kind of develop things and digest them and sort of transcend them.

It's a bit like, I always used to read these interviews with famous musicians, and they'd say things like, "Oh, man, you play your chords and your scales, and then you forget them." And I always thought that was a bit misleading because I think what they really meant was you learn your chords and your scales so thoroughly that when you're playing, you're not thinking about them. It's a bit like if you're eating your dinner, you're Grade A with a fork. You know what I mean? [laughs]

MPc: Yep.

CE: You can stick the fork in your potato, and you're not thinking about the technique of how you move the fork and how you get it into your mouth. You just want to enjoy the food. It's kind of a similar thing to me. So you work on your technique and your chords and scales and all these influences, and it all kind of becomes part of you so that you're not thinking about that when you're playing. But there are times, sometimes, we're listening to things and thinking, "Maybe I can approach it like this or like that."

MPc: I think I noticed a double bass down on stage.

CE: That's right.

MPc: Are you going to be playing that tonight?

CE: I'm afraid so. [laughter] Yeah. That's a first for me with Porcupine Tree tonight. [laughs] We're doing an acoustic set of some old material. I've played double bass on and off over the years, and it's something that for a little while I took it quite seriously, and I practiced with a bow and everything. But of course, I haven't really had the opportunity to play it that much because I've been so busy [laughs] on tour with Porcupine Tree playing electric. So I've been practicing at home, and this is a rental double bass, so it's an unfamiliar instrument, and we're doing some unfamiliar material. That should be fun! [laughs]