Richard Barbieri first came to prominence in the music scene back in the mid ‘70s as a founding member of the British new wave band, Japan. After five successful albums with the band, Richard had developed a reputation for being both a master synthesist and sound designer.

Over the years, Richard has written columns for popular electronic musician magazines as well as a designed/programming sounds for various synthesizer manufacturers.

It wasn’t until joining the progressive rock band Porcupine Tree in 1993, however, that Richard Barbieri really became a household name. OK, perhaps we’re overstating the impact that progressive rock has had on the general population, but whether you’re a keyboard player or just a fan of this incredible band, you should be quite familiar with the lush soundscapes that Richard paints with his synthesizers.

Unlike some of the more technically dexterous prog keyboard players (like Jordan Rudess or Derek Sherinian), part of what makes Barbieri’s sound so special is that he comes from the Brian Eno school of playing more than the other guys in his genre. He’s like an impressionist painter collaborating on a graphic novel with illustrators who draw with finely pointed pencils, a juxtaposition that helps to give his band a distinctive and unique sound.

We caught up with Richard in New York City during 2009’s The Incident world tour. As with many great musicians we talk to, Richard is extremely humble. In fact, he tends to think less of his talent for playing than any of us could possibly imagine. To Richard we say, don’t forget: just because Monet didn’t paint with the precision of da Vinci didn’t make him any less of an outstanding artist.

I’m always searching for space and the right sound at the right time.

MPc: Why don’t we start talking about the new record, The Incident, from your perspective? Tell me about your approach to the keyboards on this record compared to the last couple of records: Fear of a Blank Planet, In Absentia, Deadwing.

RB: My approach hasn’t actually changed, I don’t think, for the past 25 years. What has changed is just the context. I’ve played rock albums, jazz albums, electronic albums, singer-songwriters, but I have a certain approach to the way I do things, and I don’t particularly change that.

It all stems from not really being a keyboard player. I found out at an early age that I wasn’t going to be able to play keyboards like the people I was watching and the things I was into at the time, which was all the mid-Seventies prog bands. And it wasn’t until I heard Roxie Music and I loved the kind of glam stuff in the ‘70s and predominantly early ‘80s, I kind of saw that there was another way of doing it and I became more interested in sound than the actual physical art of playing, so I started to develop more complex sounds rather than complex playing. And it just went from there really. I kind of made one note do a lot of things rather than 500 notes with the same sound.

My approach has kind of stayed the same in that I’m trying to create a mood and an atmosphere and the sounds are kind of important, so that’s what I think of when I first come to any piece of music. From that perspective I haven’t really changed.

MPc: Was your approach any different on your new solo record, Stranger Inside?

RB: I was pretty influenced as well in the ‘70s by Krautrock — guys like Can and Neu!, which had very repetitive rhythms, very groove-oriented rhythms, that kind of thing set in a trance-like motion throughout the music. So I think that was the beginning, really, of trance and techno, and I’ve always liked that.

I like something to develop over a period of time and I guess that’s what you can do with a solo album — you can kind of set the tone and let it develop the way you see and you’re not searching for that space. And I’m always searching for space and the right sound at the right time. So maybe some of those influences will be coming through more.

MPc: On the new Porcupine Tree album, I felt like the keyboards were mixed a little too quiet compared to the previous records.

RB: I don’t know really, they’re always mixed too quiet, really, with Porcupine Tree (laughs). You see, you can change the perspective of music dramatically with levels, and it’s just something I got used to over the years. With Japan, the keyboards were way up front, you know, and that completely changes everything. The parts you’re playing, which are quite weird parts with weird sounds, can actually make that track sound quite interesting because you’re focusing on the stranger side of it. With Porcupine Tree, the interesting sounds tend to get mixed in with everything that does create a kind of atmosphere, but it might be interesting to have that pushed further to the front.

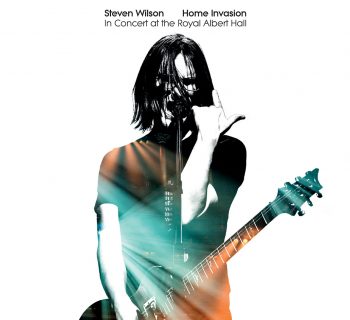

MPc: On The Incident, what percentage of it would you say was finished works that Steven brought in versus collaborative writing?

RB: Well basically the second disk, which is four tracks, came out of group improvisations and being together in the studio and working on those tracks. Added to that second disk is also twenty percent of The Incident, which also came out of the band being together and trying things out. The rest is basically what Steven had before, so I’d say a good seventy to eighty percent of the main disk Steve had written, so it’s a case of kind of enhancing that, trying to get your personality across as well, trying to find a space, and that’s the kind of interesting part of working in a band. We’re all fighting for our space.

“I keep trying to cut down the set up but it keeps getting bigger.”

MPc: How democratic is it within Porcupine Tree?

RB: It’s pretty democratic actually, but if somebody’s got a very strong idea about something, then I think the others are happy to go with that. If somebody feels that strongly and takes the lead, then I’m happy to go with that, because they’ve got real conviction for it, that’s fine. We all feel that way individually about various parts within the recording. There’s a certain amount of stuff that we veto, we don’t like, we say “no,” whatever, and Steven has to live with that. Because we have to live with the fact that he’ll bring in some stuff and be very precious about the demo and how it’s exactly the way he wants it, so obviously our contributions are to enhance rather than to change.

MPc: In my own band, we drive the keyboard player crazy because most of us play keyboards and have our own contributions that we bring forward.

RB: I think it’s kind of a natural disposition of some musicians to be interested in others’ contributions. I mean, I’m very much like that. When I’m making a solo album, the most important thing for me is when other people come and play on it. And that’s the part I look forward to the most. I love that! I just want lots of people to come and play on it, because I’m interested in the context. I’m interested in what they’re going to do. Probably someone like Steven, he’s more interested in what he’s going to do rather than what other people are going to do. It’s almost like the other people are a necessity, which does improve the music, but he’s also worried it might be the wrong thing. So there’s two types.

I’m not particularly interested in myself, you know. I mean even in conversations, I prefer to listen rather than to talk about myself. Same in music. I think most peoples’ personalities transfer into their musical personalities as well and I know what I’m going to do. I might surprise myself sometimes, but I’m still more interested in what someone else is going to do to my music. Like I said earlier, I like the context. That’s why I’m a member of a band and I’m not a solo artist. I make solo albums but I don’t feel comfortable promoting myself. I think my best work usually is when I’m working with context.

MPc: Something I noticed when you were playing on the Fear of a Blank Planet tour… You were wearing Bang & Olufsen ear-bud headphones as opposed to true in-ear monitors.

RB: Yes. I was at that stage when the thought of isolation was very scary and also the [B&Os] had such a lovely sound, especially for the keyboards, because you know the frequency range of the keys could be anything and it’s just perfect for bass and real highs and real high fidelity sounds.

MPc: You could really hear enough through them?

RB: Well I got to a halfway kind of balance where I could hear my stuff really well. I was getting obviously quite a lot from onstage — probably way too much, but I managed to do it. But I’ve since gone the other way. I have full in-ears with a couple of little ambient holes in them, so they’re ultimately in-ears, and the ambient holes let in a little bit, not much… I just couldn’t find anything I liked the sound of. I bought more expensive headphones but nothing sounded as good, and of course I now have these Ultimate Ears ue 7’s and they sound absolutely amazing, incredible. And you get the same mix every night.

MPc: Now let’s go way back. What was your first synthesizer? Do you remember which one?

RB: Well yeah, my first synthesizer was actually the [Roland] System 700 Lab Series, which is kind of a companion module to the big system. I think they used it in universities to teach people so it had aspects of all the parts of the 700. It was hard-wired but it was semi-modular as well so you could use the patch plays and it basically didn’t make a sound unless you did something to it to make a sound. So that really gave me a good education and it got me into programming because nowadays you have a thousand patches on every keyboard with every sound you could think of, but in those days you had to create it yourself, so that’s where I had some talent, because I didn’t have the talent in the playing department. It made me understand about how synthesis works.

MPc: How do you build sounds today? Do you start from scratch or preset and modify it to your need?

RB: I only use my own patches anyway, so if I’m quite sure where I want to go, there’s usually a patch that I’ve got that’s roughly in that area. But as well I’ll start from scratch completely. I’m more influenced by sounds that we hear every day, or even emotions. It could be anything. I’m not necessarily influenced by listening to a record or anything, “Oh, I want to use that sound.” That doesn’t occur to me, really. So a lot of my sounds are derived from every day sounds.

You get this weird thing when two sounds combine, you know, like when you try to tune in a radio when you get half of one song and half of another, and you think “That’s the most interesting piece of music I’ve ever heard,” and then you get to either of them and they’re both quite boring. And that’s what you hear when you walk around, you walk through airports, train stations, cities, you get all sorts of combinations of sounds.

“My influence comes from everyday things and from emotions, from atmospheres, places, films, sounds, rather than music.”

MPc: How often do you bring in new equipment? Are you a “gear junkie?”

RB: Yeah, I’m a bit. It does keep changing. I keep trying to cut down the set up but it keeps getting bigger. (laughs)

MPc: What’s currently making you the most excited?

RB: Well, I had hopes to bring in the analogue gear but it’s been so problematic with all the freighting all around the world, and [the gear] always goes down after a couple of weeks, so then you have to bring a spare, and then you’re bringing around tons of stuff and it’s quite difficult. So I’ve kind of gone for the safer option of a combination of things, really. The latest thing I bought is a little Prophet, I suppose. It’s an emulation. Although it’s got exactly the same back, but in miniature form, so it’s a hardware back of the Prophet, made by Soniccore, and I use that because I can actually change the sounds as I’m making them, and I know where everything is, and I’m very comfortable with that interface.

MPc: Did you consider the Prophet 8 tabletop [Module] version?

RB: I did, but it’s not really like a Prophet. It has more in common with the Oberheim, actually. But no, this one is a complete emulation of a Prophet. It’s pretty accurate. And of course that goes through hardware for distortion pedals, delays, modelers, and all kinds of stuff. In fact, it ends up going through an old [Yamaha] SPX90. For some reason this old 12-bit piece of gear has always worked well with the Prophet. So that’s new. I’m using the V-Synth, and the Access Virus Indigo, I use that a lot.

MPc: What about plug-ins?

RB: I use [Propellerhead] Reason. I’ve developed sounds for them, for the latest version of Reason. There’s a synthesizer in there, Thor, and you get one of my folders as standard when you buy it. And there’s a lot of interesting instruments in Reason as well as a good software and you can set up really complex chains of effects. So I use that quite a bit.

I’ve got some little analog pieces that I might use one night, they’re all there just in case. The main reason the set up is like it is, it’s because of the way I record when I make the album. So I set myself a problem for when I do it live because I don’t just play a piano through one track or an organ through one track. It’s not that simple. It’s made up of lots and lots of parts and lots of different sounds. So of course when you come to do the album live, you realize, “Oh, I’ve got to be playing this here, that there, this keyboard, that keyboard.” To recreate it you almost have to replicate your studio set up, what you did at the time.

MPc: When you record the Porcupine Tree records, do you use virtual piano sounds or do you play on acoustic piano?

RB: Well, on the Porcupine Tree albums, Steven plays piano. If he’s written a song with piano, I think it’s better that the songwriter plays the piano. It would be too weird any other way. If Neil Young sits down and writes a song on piano, he doesn’t want somebody else to come along and try to play it. So he gets the kind of phrasing that he wants and the feel that he wants. Usually, he mic’s up an old upright that he has at home, which has a lovely sound. [But] this time he used the studio piano.

MPc: What do you use to replicate the piano sounds live?

RB: I have the Piano Refills from Reason, which are 24-bit multisampled pianos. They’re pretty good.

MPc: Given your background as more of a synthesist than a traditional player, do you prefer controllers with plastic keys or weighted?

RB: I like to play cheap, plastic keys. (laughs) I mean, I play piano — I’ve got my own way of playing. My way of playing is probably more in the mold of Erik Satie or Mark Hollis from Talk Talk. It’s very gentle and very mellow tones on the piano. It’s kind of almost “not playing” it, if you know what I mean. It’s just playing it hard enough to get the sound to come through. You know, you can get ten keyboard players to play the same chord and everyone would play it differently. Whereas other keyboardists will funk the hell out of them, they like nice big old chunky keys and they really hammer at them, but that’s not for me. (laughs)

MPc: Let’s talk a little bit about A Stranger Inside, your second solo album. What was your motivation behind this record?

RB: It was kind of a companion to the first one, really. This one was probably a bit more personal. I mean obviously there’s no lyrics or vocals, but to me there’s always a meaning to the tracks and there’s always a start point and there’s always a concept. Of course that’s hard for people to pick up on, but it’s important for me to have that motivation there, and that general concept to work with. A lot of the tracks were… another self was within me, almost another personality, and it’s almost like dealing with things and trying to bring that side of me more to the fore, and to try to understand that part of me. Sounds like a psychological nightmare (laughs), but I suppose it was a bit of a cathartic thing to sort of bring out a darker side that is there and try to bring that out in some of the tracks.

MPc: The title track of Porcupine Tree’s new CD, “The Incdient,” seems to share a lot sound-wise and style-wise with the vibe I got from your solo record.

RB: Well I think that whole sequential thing of sequences and quiet industrial sounds is something we’re quite interested in. I know Steven likes a lot of early industrial music. We like Nine Inch Nails, we like anything to do with keyboards. And I always wrote sequences right back from the days of Japan, so I love that thing where you’ve got something that’s moving and then you can start messing with the sound or fade other instruments into it. Like I used to fade tapes and voices through the sequences so they would blend in with the notes and change all aspects of the sound.

MPc: Who are some of the newer artists that have peaked your curiosity?

RB: Well, there’s a guy working with electronic music in Mexico, a guy called Murcof. It’s amazing stuff. Really, really good stuff. It’s kind of combining electronica with samples of orchestras mixed in with sound design stuff. It’s really interesting, and it’s quite beautiful as well. Electronic music is pretty good at the moment, I still listen to Boards of Canada, Aphex Twin. I tend to delve backward, to be honest… I mean I thought the last Radiohead album [In Rainbows] was brilliant, I really liked that. I haven’t heard Mars Volta but I’ve heard that’s really interesting.

MPc; Who are some of your influence keyboard players/sound creators?

RB: In the early days, the thing that got me to synthesize was listening to Brian Eno and I was very interested in Stockhausen as well. I don’t know if you’ve heard any of those recordings from the ‘50s, a very abstract sound, working with sort of primitive oscillators and controllers, and I kind of tried to incorporate that abstractness into the songs, which I did in Japan, and continue to do. So those were quite an influence on me.

But as I said, probably more of my influence comes from everyday things and from emotions, from atmospheres, places, films, sounds, rather than music. So many types of music I love to listen to, but it doesn’t come out in my work.