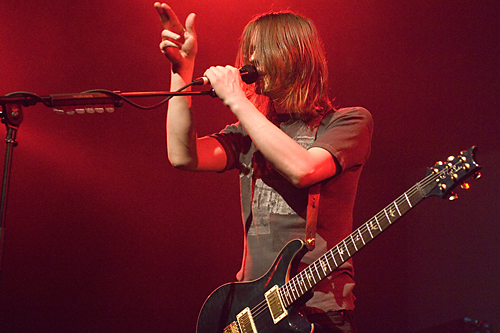

As the drummer for Porcupine Tree since their 2001 release, In Absentia, Gavin Harrison exploded onto the drum scene with his intricate fills, solid groove, and amazing independence. His popularity has risen so dramatically that he is now recognized as one of the foremost progressive rock drummers in the world today, punctuated by his recent honor being voted Best Progressive Rock Drummer in the 2007 Modern Drummer Readers Poll.

However, in spite of fame and success, Harrison remains incredibly modest and does not forget the long road and hard work it took to get him to this point. We had a chance to speak with him during the Fear of a Blank Planet tour and discuss the new album, as well as learning quite a bit about his thoughts on the recording process, gear, and much more.

I really don’t want to be in a performance mode in the recording studio.

MPc: Tell us about your approach to the drum parts for the new Porcupine Tree album, Fear of a Blank Planet.

GH: I’m always looking for a good rhythmic design, a solution to the piece to try to make some unique parts or some unique grooves or fills that mean something to an individual piece. We had the chance to go out and play most of the material live before we got to record it, which is something bands used to do back in the Seventies. Usually, you record an album and then you go out and play it and at the end of the tour you’re like, “Oh man, I wish we could re-record the album. We’re playing so much better now.”

You know, things evolve, certain little nuances appear and you find better ways to play one section to another section or you get a better idea. So, we got to play twenty shows of the new album, ten around Europe and ten around the States, and that was incredibly useful. So when I went into the studio to record the drums for those pieces it was just a matter of getting down a good performance. I wasn’t looking for solutions and ideas – I had already worked out the plan.

We had also written some other pieces that were based on jams that we had had at my studio and there was a big difference recording those as opposed to the ones we had already played live. Those songs were very hard to make them sound as smooth and as evolved as the other pieces, so it was a very useful thing to go out play. An even then, they evolved since when we played them live and then recorded them. And even now – they’ve evolved since then. So I guess we got somewhere up the ladder, but you never get to the top of the ladder at the point you record it.

Maybe that’s the treat of what happens in a live DVD. You see the songs that we had recorded on the DVD [Arriving Somewhere…] we did in Chicago. We’re performing songs we did on In Absentia and Deadwing. From my point of view, the band are playing them better there than we did on the record because we had a chance to really play them in and little things happen, magical things that happen along the way.

MPc: What was it like recording the live DVD, Arriving Somewhere…?

GH: Well, it’s quite a pressure. We were looking for somewhere where we could do two nights to relieve the pressure of the idea of it being one shot and no chance to ever go back. So we were fortunate enough to get two nights at Chicago’s Park West and that took the pressure off the first night of being the only night. You know, if you make a mistake you think “Awe man, there will be a DVD with that big mistake on it,” so we had a chance to play some of the songs again the second night. In fact, without that pressure of it being one night we actually played better on the first night because you know it’s not all shit or bust and you’ve got a chance to relax a bit more. But, it is a lot of pressure to get it all down knowing that it’s going to be preserved forever.

MPc: Take us through Porcupine Tree’s writing process. Specifically, how do you write masterpieces such as “Anaesthetize?”

GH: “Anaesthetize” was a song that Steve generated pretty much on his own. He presented a skeleton demo to the band that had a lot of the parts in demo form and we all individually worked on them. We recorded demos first. I recorded the drums to “Anesthetize” about six months before we went on tour and played it live, and then I recorded the drums for real after the live tour. So I did a kind of a demo of what I was going to do, but I knew it was only going to be a demo at the time. That gave me a chance to try a lot of things out – try and change sections, try and find ways that I want to play certain parts, and try to get it all in line before we were going to go and play them live.

MPc: Did you track the drum parts to these demos using your home studio?

GH: I did all the drums on the record at home. Everyone sort of did their own parts individually, but since we played most of the songs live it wasn’t really a problem because we all knew what we were going to do. As with the last two albums, I just recorded them on my own at home, which gives me the luxury to do ten or twenty takes, or if I just want to do one take, or if I want to spend four hours on one little bit I can do that without anyone being bored sitting there looking at their watch, or, huge amounts of money being spent in a massive studio.

You could be blowing $3,000 a day easily in a big studio, and you want to experiment on something that takes four hours, and then you decide you don’t like the result of it. That’s a lot of money that just whistled by. (laughs)

MPc: It certainly takes the pressure off.

GH: Yes, and when there’s a lot of people in the studio – sometimes record company guys come down and management guys come down, and you feel like you’ve got to perform. I really don’t want to be in a performance mode in the recording studio. Like on the DVD, it’s more of a performance. During recording, I want to play and then consider. I might want to take two and a half hours off and just scratch my chin and think about it.

MPc: I’m sure recording at home on your own time creates a more conducive atmosphere for being creative.

GH: It does, but the down side is that you don’t really get any feedback because you’re on your own. So, although there are a lot of positives to it, there are a couple of negatives to it. There is something about all four guys being in the studio together which is nice, which we did for In Absentia. Even though within In Absentia sessions we all played individually we didn’t track together. There’s an atmosphere with the four of you together and the sort of feedback that you get in which is quite nice, but, probably the upside of it outweighs the downside of it in terms of the relaxed luxury of going at any pace you want.

Some days you get up, play a couple of songs and think, “Uh, I don’t really feel like it today, I’m just going to go out and do some shopping, go for dinner and start again tomorrow.”You know, people used to do that in the seventies and spend $3,000 a day and just waste the money (laughs), but it’s quite easy to have that luxury at home.

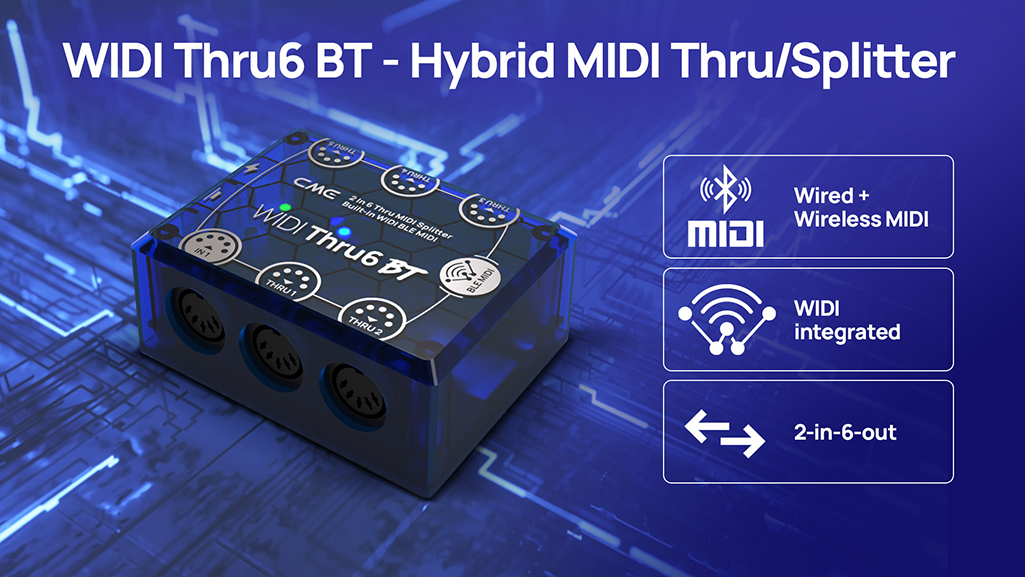

MPc: While we’re talking about home recording, what equipment do you use in your home recording studio?

GH: I’ve got an old Mackie analogue desk, a 32:8 bus. I use Apogee digital converters. I’ve got a huge amount of microphones which I’ve collected over the years, mainly from working in studios and remembering which microphones I really liked the sound of. I do a lot of experimenting with mics and placement. I’ve got a huge live room at home, which I’m lucky enough to have. I’m placing different mics at different distances. It all gets recorded into Logic Pro on a Mac. Then I’ve got the chance to fiddle around with the effects, the delays, the phase reversals, things like that. But I very much want to get a performance and a whole track down.

I don’t chop every couple of bars. I can hear it when I’ve edited between lots of different performances, so I try and pick one. I’ll try and do four takes that I really like of each song and then I’ll pick one take that I think has the best vibe to it, and I might cut in a couple of other bits from another couple of takes that I thought were better than the main one. But really, no more than a couple of cuts or else I start to hear not a difference in sound, but a difference in attitude. And that’s another luxury you can afford to do at home.

MPc: How long did it take for you to feel comfortable recording at home?

GH: I’ve been using Logic for about fifteen years but my studio at home has just slowly evolved over the last ten. Pretty much I’ve had the same desk and the same microphones for the last ten years, but the recordings have got progressively better as my experience has gotten better – nothing more really than just experience and experimentation. Moving microphones slightly, changing EQs slightly, tuning the drums differently and just, you know, moving towards a better drum sound over the years. [Fear of a Blank Planet] is probably a better recording than Deadwing was, as my experience engineering got better.

MPc: We had a chance to see Porcupine Tree recently on the Fear of a Blank Planet tour and noticed many of your songs are accompanied by video. Is it a challenge to stay in synch with the video?

GH: No, no. Some of the songs that have a video I’m playing to a click track.

MPc: Which program are you using to play the videos?

MPc: Which program are you using to play the videos?

GH: We’re using ArKaos – it’s a VJ program, that’s what they call them. It’s just triggering the start point of the film and the film is being created to the original mix. So we give it to our guy – our Danish film director, he composes the film to the track, then we play the song to a click which is in perfect sync with the film. So, all the changes of mood in the song, or some of the accents in the song, are picked up by the film. It looks, I suppose, if no one understands it, it looks like magic.

MPc: The video is choreographed very well.

GH: Yeah, exactly. There is obviously a method behind it all to make the movie perfectly in synch with the band. And we’re all playing exactly to a click to keep us in the perfect tempo all the time.

MPc: There is one video, in particular, we enjoyed for the song “Sleep Together,” where an animated robot is moving in precise movements to your snare and bass drum hits.

GH: Yeah, it’s great, isn’t it? That’s a Polish director who did that film. That’s a stop-time animation. He also did a film for us for a song we did on the last tour called “The Start of Something Beautiful.” And he did a short animation for us, and we loved it. You know, it’s not typical of the other films – it’s a completely different style from the latter and it seemed to suit this song “Sleep Together,” and it looks amazing. I love it. I think it adds something to the overall concert experience that you have films that are sympathetic to the songs and the vibe and the lyrics, and they’re in sync with the music so they’re doing something in time with what we’re playing.

“I played the drums in every possible way except with a pair of sticks on the skins.”

MPc: Porcupine Tree has released a 5.1 surround mix for both Deadwing and Fear of a Blank Planet. Were you involved in the 5.1 mixing process for the recordings, and how are the drums mixed differently for surround sound?

GH: I wasn’t involved in that – that’s something Steve did. He likes to keep the drums pretty much stereo in the front speakers and use the ambience more in the side and to the back rather than panning the drums all around all over the place which would feel very unnatural. It would feel very weird, like you’re sitting in the middle of a drum kit which, apart from another drummer, would feel very alien to anyone who wasn’t a drummer, if you panned the drums all over the speakers. I think the drums are more cohesive when they’re all in the front speakers to my ears, but you hear ambience coming out the rear speakers.

I think the keyboards come out best in 5.1. You really get some of the subtle nuances that Richard’s doing and they come out in some of the rear speakers slightly separated from the other music and you get to hear a lot of the great stuff he does.

MPc: One of the extras on the Arriving Somewhere… DVD called “Cymbal Song” is an amazing piece. How did you come up with the idea to compose a song entirely with cymbals?

GH: Yeah, it’s also on the drum instructional DVD called Rhythmic Horizons. We were looking for extras to stick on the DVD of Arriving Somewhere… in lieu of sort of a documentary back-stage thing which we had planned, but which would take too long to edit. I said, “Look, you can take the ‘Cymbal Song’ from my DVD.” In fact, I sat with Steve and we did a much more literal 5.1 version of the “Cymbal Song.” The screen splits into nine sections and it’s panned around the speakers so it’s like you’re sitting in the middle of that cymbal film and the things that are coming from the bottom left are coming our rear left. The cymbals that are coming out of the bottom right are coming out of the rear right speakers and it’s logically panned, you know what I mean? So you do get a much greater sense of the surround on the cymbal film.

I came up with it because I was just kind of playing around with a cymbal on my lap one day enjoying the muted and semi-muted elements. I’d pick up things and play them. I’d pick up a wastebasket and play it with my hands. Inanimate objects just seem to always have some strange rhythms hidden inside. I started playing and I started wondering if I doubled it and played it in stereo and it sounded great. Then I picked up some other cymbals and I thought, “Wouldn’t it be cool to make a piece that was all cymbals all played in an unusual way?”

I never actually get a stick out and play a cymbal in a traditional way. So, the hard bit was composing a four-minute piece. It was great, you know… I could create these little ten second loops that sounded great, but try to make a composition that was going somewhere from beginning to end was the hard part. So I spent about a month composing it and then I spent about four weeks filming it just at home. I then actually went on and did a drum song, which is on my [instructional] DVD, and it might be an idea that I release the drum song as an extra on the next Porcupine Tree live DVD. That’s still yet to be decided, but I’d like to just for fun.

I played the drums in every possible way except with a pair of sticks on the skins. I gave myself that parameter, the same mental parameter as the cymbal film, but I would try to find every possible way to play the shells, the insides of the drums, you know, doing lots of weird things with my hands. I’d get a pipe, I’d blow air into the drums, I’d take bits off the drums and rattle them in a percussive way. In many ways it’s more creative than the cymbal film is. And, I wrote the drum film at exactly two-thirds the tempo of the cymbal film. So on my DVD there’s the cymbal film, the drum film, and then the cymbal and drum film playing together. Because there are two different tempos but they’re mathematically related, they come over as what I would call a rhythmic illusion. It’s like there’s two tempos playing at once but they’re sympathetic so there’s all these cross rhythms going on. That’s something that the people who’ve ever seen or bought my drum instructional DVD would be familiar with.

MPc: Let’s talk about your instructional videos. You’ve released two videos, Rhythmic Visions, and the one we’ve been talking about, Rhythmic Horizons. Is there a progression with these videos?

GH: Yes, and there are two books before that as well, Rhythmic Illusions and Rhythmic Perspectives. Rhythmic Visions is a lot of the stuff out of the first book that’s explained a bit clearer because I started writing the book Rhythmic Illusions in 1988 and finished it in about 1994. I was writing a column for an English magazine called Rhythm, and after about three and a half years I had so much material I decided I was going to turn it into a book.

But they all have a common theme, which is how to manipulate rhythm to create emotional effects, and none of it requires any chops. None of it requires any special technique other than a lot of grey matter – they’re like mind exercises. They’re really hard to play, but you don’t need any technique. There’s no fast thing – it’s all rudiments for the mind. (laughs) So that was the theme. I wanted to find something you can do on the drums, you can express in emotion on the drums, that didn’t involve some huge technique. You know – fancy, fast, or finger technique. And that was the theme of the first book.

The second book I just extended that theme and found lots of ideas based off the first book. The first video, Rhythmic Visions, a lot of it is based on the first book plus some unique performances, and I found better ways of explaining what a rhythmic illusion is all about because it’s quite a complicated, high brow subject to get into. And then the new DVD, instead of copying the stuff out of the second book I just started off on new ideas. So the new DVD, Rhythmic Horizons, has got a lot of new material that hasn’t been in any of the books or videos previously to that. And again, it’s all about manipulating rhythm to cause effects within the music.

“Sometimes finding your own voice means inventing some things, too.”

MPc: Let’s talk about gear now. When did you start playing Sonor drums?

GH: I started playing Sonor drums in 2001. I met with the head of the company and he seemed like such a nice guy, and I’d always had respect for their equipment, and he was interested on day one to hear what my ideas were. The previous company I was with, although I had a nice endorsement and they would give me free gear, etcetera, I never had a relationship with them or got to develop any of the equipment.

With Sonor drums there’s much more of a relationship with them, and I realized they were much – I’m saying this now, it sounds ridiculous – but I think they’re much nicer drums than the previous company. I really like the sound of the Sonor drums, and they give me the voice I’m looking for, especially in this kind of music. Just the right kind of tone I was looking for.

MPc: Do you record and tour with the same Sonor kit?

GH: Yep. In fact, they just built me a new one a few months back which I will start recording with, but the kit they built me three years ago is the kit that’s on Deadwing and Fear of a Blank Planet, and it’s the kit that I toured in Europe with. I’ve got another kit out here in the States, which is more of a logistic thing because the shipping of drum kits is very expensive. So I have a very similar kit that was an identical kind of spec kit out here. It’s just nice to not have to ship everything every time.

MPc: You play a variety of Zildjian A, K, and Z series cymbals. How did you choose these models, and what characteristics do you look for in a cymbal?

GH: Well, it’s pretty instinctive. I go to Zildjian’s artist relations office in London. They’ve got thousands of cymbals, and I sit there and take some time. I line up say, ten ride cymbals, and play all of them and one of them will just jump out at me and I’ll think, “Oh, that’s got something.” And I try ten cymbals of identical weight, size, and model and just play them all and think, “There’s something about this one I like and I don’t know what it is.”I don’t go for a pitch, I don’t go for a weight, or a brightness, or a darkness – it’s instinctive. I’ve been playing the drums since I was six and it’s something you just know.

The Zildjian Company has been fantastic to me – they’ve been very nice indeed. The luxury to have that chance to try a lot of cymbals and multiple copies of the same cymbal until I find one that I think, “Yeah, I like that,” and over the many, many, years your ears just tell you what you need. If you were totally new to the situation you’d probably just pick the highest pitch ones, or the loudest ones, or the brightest ones, and then regret it. I’ve probably done that in the past as well. But when you’re playing night after night you get to know the sort of sounds that express what you’re trying to play.

The Zildjian Company has been fantastic to me – they’ve been very nice indeed. The luxury to have that chance to try a lot of cymbals and multiple copies of the same cymbal until I find one that I think, “Yeah, I like that,” and over the many, many, years your ears just tell you what you need. If you were totally new to the situation you’d probably just pick the highest pitch ones, or the loudest ones, or the brightest ones, and then regret it. I’ve probably done that in the past as well. But when you’re playing night after night you get to know the sort of sounds that express what you’re trying to play.

MPc: How often to do you select new cymbals?

GH: Oh, I go down there about three or four times a year. Sometimes it’s because I’ve broken cymbals and I go back and replace them and they change them for me. Other times I just think I’d like to try some of their new lines – they’re always bringing out new lines of cymbals. They’ll tell me they’ve “got a new line, come in,” and I go down and try it, and sometimes I like it; sometimes I don’t like it. Sometimes I find some other cymbals they’ve got and swap out some of the old cymbals I know I’m not going to use anymore. The service they give me, especially when I break cymbals on tour – they get me new ones out straight away. I couldn’t be happier with them. They’re great.

MPc: Now, we have to ask, and we’re sure you’ve been asked a million times about the custom chimes you have mounted near your high-hat. What’s the story with these?

GH: They were created because I was looking for a little bell/chime sound. Before I was a Zildjian endorser I was buying Zildjians anyway, and I had some from the Seventies and Eighties kicking around my garage that had gotten a split in them – they were useless. And I thought one day I’m going to get some of those metal work scissors, they call them tin snips in England. I got some tin snips and cut the cymbals down. I made a little custom piece that goes on the end of a drill so I could spin the drill with the cymbal attached to the drill and then onto metal work paper, and files to file it down to a perfect circle. And I just experimented until I found the tones I was looking for. So I made five little cymbals, and they sound great to me.

MPc: Since you have a good relationship with Zildjian, have you ever consider approaching them to create a signature series for the chimes?

GH: Well, that’s something that could happen, too. I saw Zildjian recently. I went to Boston and we talked about all sorts of designs and not only about those little cymbals, but lots of other ideas I’ve got of custom sounds. That’s a nice thing about being an endorser and being involved in products and prototypes and things like that, so I don’t know what they’re going to do. We only had one meeting about it, but I don’t know if they’re going to produce them. I kind of like keeping them just for myself to be honest (laughs). I don’t want everyone to play them.

I do a forum called Drummer World, www.drummerworld.com, and I’ve got an open thread. People just ask me questions, and that question comes up the most about what are these little bell cymbals. I’ve even given people instructions on how to do it – there are photographs and quite detailed descriptions on how to go about doing it. If you want to do it and you’ve got cymbals that are broken and just sitting in your garage, you’re never going to play them, so why not have a go at cutting them up? You never know – cut them into strange shapes, they might sound great. If they sound like shit, then you’ve lost nothing. You might be surprised. You might cut it into a square and it sounds fantastic, so, you know, do your own thing. Sometimes finding your own voice means inventing some things, too, or invent some ways of playing them. Invent some shapes of your own.

MPc: Many fans of Porcupine Tree might not know that you’re a seasoned session and touring drummer who’s worked with many international artists and bands. Tell us about some of the work you’ve done outside of Porcupine Tree?

GH: In fact, since1979, since I left school, I worked as a freelance professional drummer, which involved everything. It involved playing in café bars, in stadiums with big artists, just trying to make a living really as a professional drummer. Some of it involved touring, some of it involved playing in wedding bands, Top 40 covers bands, big bands reading charts with brass players, and things like that. Just a varied amount of stuff until I started to become more well known and became more selective about some of the things I did for the tours and recordings.

This opportunity came up when the last drummer left Porcupine Tree and they asked me, because I’m friends with Richard [Barbiari], the keyboard player. He invited me to go to New York and record In Absentia as a session drummer, which was all I was doing at the time. So I went out and they paid me as a session drummer, and at the end of the session they said they’d like me to join. I thought, you know, maybe it’s time for me to give being a band member a go because I’ve never been a band member.

You know, you work for other artists, they go on tour, and they go back in their box for a few years and then you’re looking for another gig. So that work is pretty fickle, it’s a lot of work and money, and a lot of time down and no money.

MPc: It must be a different experience for you being an actual member of a band.

GH: It’s a completely different experience being in a band. You know, I’ve been in the band since 2002, so it’s five years and it’s an interesting thing, an interesting thing to be part of the composition, and part of the production, and to make a difference in the music. If you’re just playing as a touring drummer you have to play the parts that someone else came up with and play the artist’s songs. This plays a bit more like I’m playing my own songs. You know, it’s a nice experience being in a band, a different experience. Sometimes it’s a pain in the ass, but it’s a completely different experience from being a session musician.

“If your ambition right from the start is to be the world’s greatest drummer, you’re going to be very disappointed.”

MPc: You were recently voted Best Progressive Rock drummer in the Modern Drummer Readers Poll. How does it feel to be recognized like this by your fans?

GH: It’s great! I had no idea that I’d got that sort of popularity! I know other drummers run campaigns from their website and from their band’s website to make their fans go and vote for them on these kind of things, which had never occurred to me because I had never been in any of the polls. The only poll I’d been in, I think I won second or third best drum book in about 1996 for my first Rhythmic Illusions book, and since then I’ve never been in any of the polls, not even in fifth place, fourth place or anything. It didn’t even occur to me that I’d be in any of the polls of Modern Drummer. So, to come from nowhere into first position it’s been quite a shock actually.

I found out about it a few months ago when a friend emailed me the result, I couldn’t believe it. Mike Portnoy has won the last twelve years, so I assumed he’d win every year. (laughs) It feels great – I’m sort of shocked. I knew Porcupine Tree was gaining popularity. I guess I was gaining popularity, but not on that level, and not to that kind of extent, so it was a pleasant surprise.

MPc: What advice would you give you aspiring drummers today?no, no

GH: I guess just to not give up. I’ve been through all sorts of periods in my life. Sometimes I haven’t worked in six months and I thought that I’m out of this music business and it’s really hard to get anywhere. Some people might think I’m an overnight success, but it’s taken the last twenty-eight years for me to get to this point. Maybe some people are just discovering Porcupine Tree now and thinking, “Wow, who’s this new drummer?” I’ve been around for years as a working drummer playing in all sorts of situations.

I was playing in theaters in London, in the pit under the stage doing eight shows a week reading orchestral parts with a thirty piece orchestra, a pretty faceless experience. Sometimes you think it’s just as far as you’re going to get. For me, I was just satisfied to be making a living out of playing the drums. I didn’t want to slip back to the idea that I’d have to work doing something else, you know, whatever that might be. I just really wanted to be a professional drummer and earn a living playing the drums. So, I was already happy just playing in a wine bar, that was good and I was happy to do it. If your ambition right from the start is to be the world’s greatest drummer, you’re going to be very disappointed.