Billy Sheehan is widely regarded as one of the rock world's finest bass players, both on stage and in the studio. Although critics always tell you to check out his first band, Talas, Sheehan really rose to prominence supporting rock legend David Lee Roth in his solo band, and then playing for the multi-platinum selling pop rock band, Mr. Big.

In the bass industry, Sheehan has made his influence known in every aspect from playing style, gigging, recording, and working with multiple instrument companies developing bass gear. He is also a songwriter, producer, singer, and an incredible all-around musician with an intimidating work schedule. We met Sheehan at the Newton Theater in New Jersey where we talked about Mr. Big's new record, Defying Gravity, his new signature pedal, and other gear.

I think you get a lot more done as a writer if you just leave everything behind and go in the most minimalistic thing you could possibly do.

MPc: How would you compare the differences in equipment and the recording process today versus 30 years ago when Mr. Big was just getting started? I understand that the band's original producer, Kevin Elson, is back for the new release.

BS: Right. For Kevin's session, and mostly for everything, it's pretty much exactly the same except there's no tape machine because it's all recorded to the digital disk.

Now, sometimes if we want to punch something in, for instance with the drums, before we couldn't. You had to get a whole take on drums. A couple of people tried and I remember being in the control room with a razor blade where they're cutting the two-inch tape and everybody had to leave the room and start praying, because if they made a mistake we had to start all over again. So there's a little bit of that.

Generally you had to get bass, drums and guitar in one solid take and then, from there, we'd do vocals, guitars and everything like that. So today there's a little bit more leeway to do just a drum track, then you can punch in on the middle of the drums. Your average reader might not understand, but when the cymbals are going [sssssss] and you make a cut in the middle, you'd hear a little noise like [sss-ppp-sss]. But in digital, you can do that. [Editor's Note: our readers get it, right?]

One thing we tried to do with Kevin on this record, and also on the What If… record, and the first record recorded after we got back together in 2009, was to really play the track in the studio. Actually perform it and capture it. Now, sometimes you have to go back and fix a bad note or punch in. Or, you know, redo the chorus because it's different; you played the wrong version of it or something like that; those little things are inevitable. I wouldn't want to try to paint a picture that we went in there, snapped our fingers and the album was there. There's always a little thing you got to do.

But, generally, it's just replacement of the tape machine with digital which puts you in a whole other, fantastic world of not waiting for the thing to rewind. It's quicker, it's faster—as a musician, there's much less machine interference now.

Mr. Big, Defying GravityToday we're going completely the other way. Now that the machine doesn't interfere anymore, it's actually kind of leading the way for a lot of people. We try to find a balance and perform it, play it like actual players would play it, in a room, generally together; sometimes you got to look through glass [vocal booth, drum booth, etc.], but we're all together. And that's what we do.

MPc: And then the gear—you're using your signature Yamaha bass now, obviously, but were you using Yamaha in '89?

BS: Yeah. In the very, very beginning, I think I used both Yamaha and Fender. And then I think on the first Mr. Big tour, I used my original P-bass. And that still lives in my home. In fact, a little miniature-guitar company made a tiny version of it. They nailed it, too, it's right on, and it's amazing. (check it out here) I remember when Yamaha brought me my first version of the Attitude bass and I used that on "To Be With You" and the whole Lean Into It album. And I use it a lot on the live stuff.

MPc: When you record, how many bass tracks do you take up?

BS: I mic the distorted cabinet. Because running distortion direct is always rough. Though, with the EBS pedal, I've run that direct a bunch of times and it works pretty good.

You know, in a situation where we were recording, we didn't have time or the wherewithal to get mics and cabinets and stuff. We would just run it direct and found it was pretty good. Add a little bit of EQ on it because it's going to be a little sharper, and then once you go through an amp and a speaker that kind of rounds things (the sound) out a little bit.

But, generally, it's pretty much what I use a lot. The low pickup on the Yamaha goes through the amp and then that gets direct off into an input. Then the high channel through a speaker gets mic'ed.

What I'll generally do is also add a direct—just that P-bass pickup direct, nothing on it, through a direct box, right into a channel. That way, later on, if you want to do something with tone you've got the normal, regular bass tone, as plain as can be, right there on the big old tracks, so that if you want to use just that with no distortion or anything else you can. I do that as an option when I'm doing a track for somebody else, too. Here's your chance, if you want it with a wacky sounding bass, or you want a super-deep blow-in, or you just want it clean, you got all three on there at the same time.

MPc: I could see the engineer wanting that option, just in case.

BS: Yeah.

MPc: I have listened to all of the tracks on Defying Gravity and I noticed on one of the songs I heard a C-sharp, you were going a little low. Was that dropped D or did you use an octave pedal?

BS: I've got an octave pedal, the EBS, and I've used it on a bunch of recordings. And really, I never thought I would ever use a low octave pedal. I use it on the low frequency track, using the big pick-up.

MPc: Okay, I gotcha.

BS: So it's not on the regular one. The other one I have is high frequency, but that I'll use for one or two things in my whole life. But the low on there, the EBS octave down, is great and I've used it on a bunch of records. We needed to have that articulation of a high string, and we needed a super-deep low note. It works really well. I would have been the last person to think I could go into the studio and use the octave on the bass—no way, it's never going to work. But it does, it works really well.

MPc: One thing that kind of stuck out on this album and I've always known it—Eric Martin is such a great singer. He's just… so soulful.

BS: Yeah, the tonality of his voice is just… Well, the moment I heard him, I knew. Mike Varney (Shrapnel Records), he played Eric for me because I was looking for a singer. He's like, "I've got this one guy, let me play him for you over the phone." He played it and I just said, "That's him. That's the guy. That's who I'm talking about. I want that. Who is he? How do I find him?" Blah, blah, blah. That's how he came in.

MPc: Yeah, he's so versatile it just seems like he could sing whatever you wanted.

BS: And, for me, it was more at the time we started the band '88. Everybody's trying to sing as high as they possibly could. Singing up at the highest note, you know, everybody bragging: Five-octave range! You know, placing those little ads (in the back of a trade paper or magazine) for themselves, stuff like that. I wanted Paul Rogers. I wanted Steve Marriott. I wanted a soulful voice, with depth and character. So when I heard Eric, I said, that's exactly what I'm talking about.

MPc: Tell us about your singing, perhaps your process, when you have to do harmonies, are you a singer? Are you a bass player? What's your process for that?

BS: Well, I urge every musician to sing. You save a hotel room. [laughs] And having to hire the extra guys, it's great, or me, I don't know if I'd hire somebody that didn't sing. Even drummers, I want guys that can sing and sing harmonies.

I started out in a three-piece band and we did all kinds of harmony songs. Crosby, Stills & Nash, Three Dog Night, Grand Funk Railroad. All those bands. We did tons of harmony. "Carry On Wayward Son," by Kansas. "White Punks on Dope" by the Tubes. And we did all the parts together.

I used to drive around with the drummer in his car and we'd put Beatles songs on and Motown songs on and Chicago Transit Authority, their first record, another great record. And just sing, sing, sing to it. You have to know exactly what harmony note to go to and how to stack it. Sing to the Everly Brothers, there's two, just Don and Phil. Add the third, add—either go below, above or sometimes in the middle and figure out where the note is.

So, for all the background vocals on this record, I did them all. I figured out all of them—I didn't sing them all, but I arranged all the parts and figured all the chords and everything. Like in "Be Kind," all those little harmony steps. I did that after we did those first six days of recording.

So I've always been in bands that sang, I've always sung. I don't really consider myself a singer, but I can hit the note. You know, I can get it on there. And in a harmony situation—for example, we did "Carry On," by Crosby, Stills and Nash, which is a monstrous harmony thing. We did it in Japan. We also did "It's For You," by Three Dog Night, which is another harmony showcase. Me, Pat and Paul just did it.

MPc: That's great.

BS: And it was really, really cool. So I've taken some vocal coaching from a couple of different coaches over the years. One that I've done the last few years is Ron Anderson, he's like the guy, the Man. When Bono blows his voice out, they fly Ron Anderson in to fix him, he's that good. He's done Bjork and Ozzie and Axl and… everybody. Janet Jackson, everybody. So I went to him. He's not cheap at all, as you can imagine.

But I've been singing for so long. You play a chord on the piano, you know, sing doo-doo-doo-doo. And I sing and go up a step or half-step. Or up a step and I'll get to the top and he stops. The first time I sat down with him, he stops and he goes, "Mister, you're working way too hard. Let me show you how it's done."

And he changed the whole spot in my throat where my voice comes from. Changed it completely. Now I never lose my voice and I can hit notes I never hit, ever, in my natural tone. I always sang and, when you're young, you can push higher and get those notes—because you're young and invincible. Once you get past like 35, 38, then at 40, that doesn't work anymore. We did like eight shows in nine days with Richie Kotzen (he does Ron Anderson, too) and he never lost his voice. Which is great.

MPc: Yeah, when singing, the amount of energy and air you use, is only the amount of energy used in talking, like we are doing right now. We should sing with that much and just put air behind it.

BS: Yeah, there is a technique to it. But you got to find somebody that really knows how to teach it. And I've had other people try to explain and try and teach it and they failed at it. But Ron, he's got a gift. He'll look at you and know exactly what's going on. He'll show you the exact exercise you need to do to make that happen, and man, I've surprised myself. I'm hitting notes I never hit with my natural voice.

MPc: I'm curious about the monitoring, how do you hear yourself live? How do you protect your ears?

BS: I use one in-ear and plug the other with a memory foam mattress, pretty much, jammed into my ear. So you could fire a gun off next to one of my ears, I'm not going to hear anything. But the other one has the in-ear turned down to a whisper. Pretty much just my voice and a touch of the other voices. Nothing else—no bass, ever. No—and I'll hear the bleed of the mics.

MPc: Okay, and you hear a little ambient sound coming through?

BS: Yeah. But I've never been what I refer to as a "monitor wimp." You see some guys doing it—Oh, a little high hat, a little left tom and, okay, a little less guitar and the 3D beyond this. And let me hear the key… No, I'm not that guy. Monitor guys love it. They ask to hear my voice. Two-two check, check. All right, sound check is over, thank you very much.

MPc: Gotcha. You know this song, you know the drum part, you know the guitar part, so you just…

BS: Exactly. And I can hear. I can hear everything. I always hear what's going on. But that, again, came from playing in clubs with a three-piece band. Before we had monitors, we'd turn the PA (speakers) a little bit so it kind of hit the stage a bit and that's how we'd hear what we were singing. I've got tapes from back then and we were on it. We were singing fine.

MPc: Let's go back to some of the rig stuff. I'm curious, if you're going to Paul's living room to do some writing, what are you bringing with you? Not this [large] live rig.

BS: Oh, no, just a little, tiny, microscopic amp.

MPc: What kind is it?

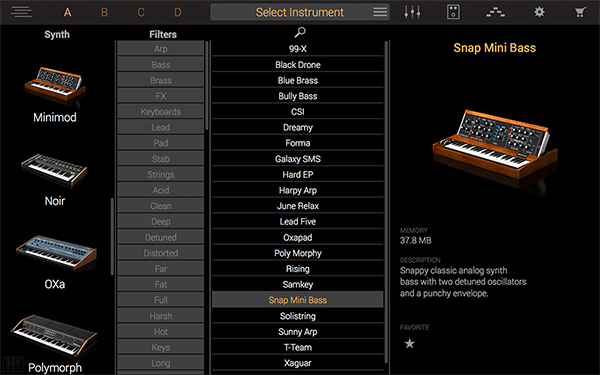

BS: Oh, a little Yamaha, the ones with the orange, glowing LEDs. Those are fine, or a Roland Cube, or just enough so I can hear what note is coming out of the bass.

MPc: What bass would you bring with you?

BS: My regular one [the Yamaha Attitude Limited 3].

MPc: How about when you're going to the drummer's house to do something?

BS: Well, I might need a little larger amp because the drums are louder, so I just use a little Hartke combo. Tiny, with no effects on it. To me the sound isn't important and effects have nothing to do with writing a song. That's wayyyy down the road. You just want to hear the bass note and the guitar chord and basically get what the arrangement of the song is. Later on, you can fluff it up, pull back, add more, go right, go left. Do whatever you want to do. But it's just basically going to hit that—you know, what key are we in? Here's the root note. How many, how long is this verse? And really make it super simple.

I think it's important for people to know, because a lot of people may get the impression that you kind of get to set up with everything exactly right and the double bass drum and the kit and the five Marshalls and pedal boards and… No, no, no. A little acoustic, the Roland Cube or Yamaha amp, quiet. You know, a shaker. A lot of times, there's no drums at all, we worry about the drums later.

That way you can really concentrate on what you're doing as a song, as opposed to messing around with your pedal board. No, give me a melody. Give me a chord change. Give me chord changes to sing a melody over and what would the bass note be? It's as simple as that.

I think you get a lot more done as a writer if you just leave everything behind and go in the most minimalistic thing you could possibly do. Then the quality of the writing, in my mind, is going to be better because your attention is focused only on how that song is. You take a great song. You usually play it on a single acoustic guitar and sing it. Even with the simple triad, three-note chords. You can sing and people go, "Oh, I know what song that is," right away. I recognize that song. Or on a piano—one hand piano. Play it and sing it. Oh, yep, I know exactly what song that is. That's all you need to illustrate a song.

So why would you have an elaborate set-up? That's kind of my philosophy, if you will.

MPc: With the companies that you've endorsed, could you share any prototypes or products that might have not made it to the production line? Were there any, like a five-string Attitude?

BS: Yeah, there was a five-string Attitude.

MPc: Oh, there was? I did not know that.

BS: Good one, too. No, there was. I wish I had one. Well, one thing that did get to market that slipped through is we did an Ampeg preamp. Which is kind of a split preamp, like I normally use with my Pierce: distortion channel and clean channel mixed together. And they're supposed to be in parallel.

MPc: What happened?

BS: They put them in series! And it wasn't until the thing was in production we realized it. And it was, oh, fuck! But a lot of people loved that preamp, and they still love it, and I see it on eBay and it gets snatched up right away. Because it does work and it does do pretty much what it was supposed to do. And series is okay. But parallel, in my humble opinion, is better to do that. It's as if I had two different faders on a console. You can pull either one up or down.

So that was good. But a couple of things really came through great: the EBS pedals, for instance ,were one of the biggest-selling pedals they've had.

MPc: I own the purple one.

BS: Great.

MPc: I love it.

BS: Excellent. And I get really good comments and emails from people that have it. The new one has a couple of things on it—this might sound stupid but, when it came out and I saw it, I thought—it's so cool. But then I thought, that couldn't have been my idea. So I asked them whose idea it was to put the socket so you can change the IC out? They said that it was my idea. I had completely forgot, because back in the day, I had a Furman PQ3 preamp, which did great distortion, but once in a while it changed its character and I had my brother put in IC sockets for all the eight-pin, 4558 dual op amps.

So, just switch them around and there it is, the sound I was looking for. I had a whole bunch of different ones—Texas Instruments, Raytheon, a couple of other ones. So one of the guys on the Yamaha Attitude page, this guy John Willis, he's a wiz. He actually sat down and took about ten different chips and tried each one in the pedal and wrote a little synopsis of how it was different. Pretty cool. (check it out here)

So the Yamaha stuff and the EBS stuff has been good. I don't endorse or use anything I don't really use. That's important.

MPc: What would a Billy Sheehan signature bass head, amplifier, look like, if you were to do one with someone?

BS: Well, it would have two parallel channels. One would be one tonality, the other would likely be super clean and pristine. And you could plug into one input and hit both of those and then adjust them accordingly. That's pretty much what my Pierce preamp did.

Basically, I had that, but instead of an amp altogether, I used external power amps. So it was basically the same thing. When I use the Ampeg stuff, the SVT-4 Pro, I use it a lot as just a power amp for the Pierce.

The [Hartke] LH-1000 I'm using now, similarly, pretty much as the power. I don't do a lot with them and I'm glad, because they don't do much. They're just volume, bass, middle, treble, thank you, good night. In a way, that's kind of cool. There's nothing on it. There's a limiter on it and a little brake switch, but I never fool with that.

MPc: You have tonal options on your bass, you have tonal options on the pedal, you have tonal options at the board, so…

BS: Exactly. I did a clinic one time in France somewhere and the amps they had for me completely died. But they had a power amp. So I ended up taking my little white MXR compressor into the power amp and that was it. No tone. No nothing. I did the clinic like that. No problem.

MPc: And that's your bass voice right there.

BS: Basically it. You need gain and you usually don't hit a lot of EQ.

MPc: As you travel from venue to venue, what are you looking for in your setup to achieve your signature bass sound?

BS: Well, I can work with anything eventually and I can get used to anything eventually. When I'm playing the bass live I want the audience to feel like it feels when I'm in a quiet room without an amp. And the interesting thing about that is, when you play an instrument sitting down with no amp, it has X amount of dynamic range. And, as soon as you plug it in, that dynamic range goes through the roof.

When you play it through that amp, it's suddenly complex and jarringly different, because your dynamics are different. So for me, compression makes the bass feel the way it feels when it's not plugged into anything. The bass itself, metal strings on wood, it does not have a lot of dynamic range.

MPc: Okay, yeah.

BS: But you plug those pickups in and suddenly you have dynamic range, so your loudest note is way too loud. The quietest note is inaudible, and some guys like that. For some guys that's the thing, that's what they're used to. But for me I practice a lot with no amp. Everything's there—harmonics are there, every nuance is there, but when you plug in, you lose some of that. So I basically try to set up my setup so that I can get that feel of me sitting in a room quietly.

Photos: William Hames