In the world of technical rock/progressive/fusion drumming, the “best of the best” list is a short one, filled with names such as Peart, Portnoy, and Porcaro to name but a few. Over the past decade, though, a newcomer has joined the ranks of the drumming elite, and while his last name doesn’t begin with the letter P, your short list of the rock world’s finest drummers easily deserves to include English drummer, Gavin Harrison. While he may not be a household name yet (outside of families that listen to the highly praised, British progressive rock band, Porcupine Tree), Harrison is a true master when it comes to combining technical finesse, tone, and musicality.

Most musicians don’t realize that Harrison’s illustrious drumming career began more than a decade before joining Porcupine Tree, having played on records from artists as diverse as Level 42, Paul Young, Go West, Dave Stewart & Barbara Gaskin, Iggy Pop, Lisa Stansfield, and more. Today, Harrison plays drums in yet another English prog rock band, the legendary King Crimson, as well as collaborating in the prog/fusion group, 05Ric.

On his latest solo release, Cheating the Polygraph, Gavin Harrison has taken classical and big band jazz to dizzying new heights, and rock drummers will be in awe of the results. Five years in the making, working with jazz composer/musician, Laurence Cottle (who has also seen his share of contributions to the world of British prog and metal), the pair assembled a collection of classic Porcupine Tree songs that have been reimagined and transformed into incredible instrumental works performed by an outstanding team of jazz musicians. This is brass section goodness, guitars and synths replaced by trumpets and French horns and trombones and more.

Harrison has published instrumental DVDs and books, and is a popular drums clinician, too. This is a man who loves the drums: he loves to play them, and he loves to share what he knows about them with others. It should come as no surprise, then, that he was happy to talk with us about the new record, as well as his techniques both behind the kit and in the studio.

The bass was so loud my eyes were vibrating in their liquid.

MPc: Cheating the Polygraph is a fantastic big band jazz record. When did you come up with the idea, and how did you go from conception to actually making the record?

GH: Well, it was quite an easy start because I was asked by the daughter of Buddy Rich if I would play at the Buddy Rich memorial concert in 2009, and Cathy Rich said, look, you can play any of Buddy Rich's famous big band charts with his big band, but we'd really love it if you could play a song from your band. And I said, oh, well, I'll have to think about that because there's nothing obvious in the Porcupine Tree catalog that's ready to go.

And I thought for a little while about which song I could do, and then I thought, well, if nothing's obvious, then go for the absolute opposite. So, I chose the song "Futile," which is kind of metal, really heavy—probably the heaviest thing that Porcupine Tree ever played, a song that I wrote with Steven Wilson in 2002. And so, I found myself around the house of Laurence Cottle, the arranger, and I played it to him, and I said, “Do you think it would be possible to arrange this for big band? I've got a plan on how we could do it.” And he did, and it came out really nice. Ironically, the concert didn't go ahead. The Buddy Rich concert didn't go ahead at that time.

And I thought for a little while about which song I could do, and then I thought, well, if nothing's obvious, then go for the absolute opposite. So, I chose the song "Futile," which is kind of metal, really heavy—probably the heaviest thing that Porcupine Tree ever played, a song that I wrote with Steven Wilson in 2002. And so, I found myself around the house of Laurence Cottle, the arranger, and I played it to him, and I said, “Do you think it would be possible to arrange this for big band? I've got a plan on how we could do it.” And he did, and it came out really nice. Ironically, the concert didn't go ahead. The Buddy Rich concert didn't go ahead at that time.

But I used to play at drum clinics and things like that, and I asked Laurence if we could do another piece, which is actually the song "Cheating the Polygraph," but we took a completely different approach to that. And once the second piece was done, I realized that there was a possibility that maybe we could make a whole album like this. And the theme, the cohesive theme, would be Porcupine Tree songs. Why not?

And that was really the moment when I decided that it could be done. It would just take a really long while. The first two songs took probably 18 months, so I knew I was going to be in for a very long haul. But there was no time limit. There was no record company. I was just paying for it myself. So, why not?

MPc: For the recording, for your performance on Cheating the Polygraph, did you play on your standard kit, or did you switch to a jazz kit? What changes did you make?

GH: No, I didn't make any changes. It's my standard kit. I did consider the idea of playing it on a jazz kit, but there's two problems. One, I'm not trying to make a pastiche. It's not a tribute to jazz drummers. The jazz drum kit sound wouldn't have worked on the whole album because there's some songs like "Anesthetize" and there's some songs like "Halo" and "Hatesong" that wouldn't have worked on a jazz kit.

And thirdly, it's not really my voice. I've already got a sound, which is my regular kit. So, I thought, well, I'm not trying to make a tribute album, I'm not trying to make a covers album, so I should use the sound that's most comfortable to me. I wanted the drum sound to be pretty much consistent throughout the whole record, and I recorded the drums almost at the end of the record. We worked with demo drum recordings up until the end, and then I thought, I'm going to do all the drums again in the space of about two weeks because I want the sound to be the same on the whole record. I want it to sound like I've just sat and played the whole record.

MPc: Cool. Now, are you also classically trained in other instruments besides the kit?

GH: No. I play bass, I play guitar, I play keyboards, but all very, very badly. [laughs]

The ride really had to be right... but it depends what the other instruments are.

MPc: Nice. Now, historically I've noticed you playing with a match grip, and I was wondering if you mixed that up—again, with the whole jazz theme—to further suit the vibe of the material?

GH: No, not really. I occasionally play traditional grip in a very light section where I'm looking to play some delicate sort of ghost-notey things. Even now, even in a Porcupine Tree concert or King Crimson concert, I might occasionally switch just for a very short time to play traditional because there's two or three things that just become a little bit easier in traditional grip. But no, ninety-five percent of the time I play match grip.

MPc: Oftentimes I've seen that you find interesting ways to make rhythmic use of non-instruments, and one particularly cool thing I remember you doing was playing a drum fill across the rims of your toms during the Porcupine Tree song "Hatesong." I'm wondering what inspired you to do that.

GH: Oh, I'm not the first drummer to do that. You find whatever sounds you can on the kit. I don't know if you've ever seen my "Drum" and "Cymbal Song," which are on YouTube.

MPc: I love the "Cymbal Song." [song in which Gavin plays nothing but cymbals]

GH: Once I did the "Cymbal Song," I thought, I wonder if I could do a drum song and try to play the drums in every possible way except with a stick on the skin. And yeah, you can get a lot of sounds out of a drum by avoiding doing the one most obvious thing.

MPc: Indeed. Now, let's talk about your Sonor drums. What led you to play Sonor and which kit you primarily use today?

GH: I started to play Sonor drums 2001. I've always admired them. When I was a kid, they were quite popular in the '70s. There were a lot of pro drummers playing Sonor drums. They were always very expensive drums because they're just built to very, very high quality. I've never met a professional drummer who didn't admire them. They're really built at the highest possible standards. All the pro drummers I know, I'm sure they'd be more than happy to play a Sonor drum kit if they had to, if they turned up at a studio and it was a session where the guy said, don't bring any equipment because we've got a kit here. I don't think any of them would think, “Oh, no.”

They're just amazing, very well built drums. They've been building them the same way for a very long time. I've been to the factory a few times. I've got a good relationship with the designers. We built a signature snare drum together. I've designed all sorts of little hardware bits and tuning keys. They're a very progressive, forward, modern company.

MPc: Tell us about the specific kits that you play.

GH: Well, the one I have in my studio at the moment is the blue tribal SQ2 kit. And it's pretty much the same configuration I've been playing. My kits have looked the same for about the last 25 years in the way that I set them up and the sizes and the way I spread it out. It's pretty much the same with the cymbals, too. Maybe some drummers would think it's too large for today's world. A lot of the drummers that I knew 25 years ago who had kits this size have all now stripped back to a much more minimalistic kind of bass drum, two toms and a snare kind of setup.

I stuck with it because I like the range of tones. And I've played this configuration so long that I don't even have to think. I can just play with my eyes closed. I know where all the sounds are, so it becomes really second nature. I never have to kind of think, wow, where am I going now? My hands just go there. That's a nice place to be.

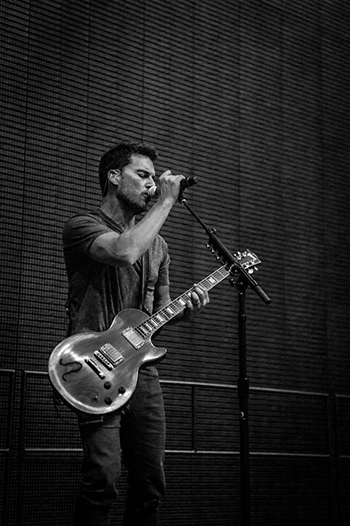

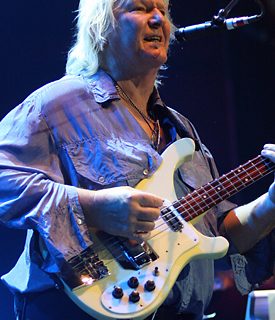

Photo credit: Lasse Hoile

MPc: Your kit is dominated by Zildjian cymbals. What would be your most essential cymbals to take a gig, and in particular which hi-hat and ride cymbals do you use the most frequently?

GH: I'm never really put in a position of if you just had to save one cymbal, a desert island cymbal. I've got a large collection of cymbals that I already had before I joined Zildjian, because I was buying and collecting them pretty much from when I left school. If I could afford a good cymbal, I would buy a Zildjian cymbal, and chances are it's still sitting here now, if I haven't broken it.

I don't know… I go through phases. There's been periods where I've played 13-inch K hi-hats, I've played those for about ten years. Now I'm using the Constantinople K 14-inch hi-hats. And for this particular record, this Cheating the Polygraph, the record—what's this called? It's called a Custom Dark Complex Ride in the K Series. It's a 21-inch ride.

Now, I've got the luxury of having a studio at home, so when I do a session or I'm going to play on a song, one of the first things I start thinking about is which cymbals am I going to use because that really dictates a lot about how I'm going to play. And it's very easy for me to just do a quick half a song, playing with a certain cymbal, and then listen and try to evaluate if it's really working for that song.

With this Cheating the Polygraph record, there's quite a lot of cymbal work, so the ride really had to be right. Sometimes you can find a ride cymbal that sounds fantastic, but it depends what the other instruments are. If there's distorted guitar, if there's heavy bass or thick keyboards, suddenly your fantastic cymbal sound can just disappear in the mix. And that's true very much of the bass drum as well. You can get a great bass drum sound, and as soon as you bring the band in in your mix, the bass drum just disappears, and you think, where has it gone? It's loud, but it's just getting eaten up in frequency.

Now, with the frequencies of trumpets and saxes and trombones in a big band setting, the ride cymbal really needs to cut through quite clearly. But I don't like really metallic, industrial sounding cymbals. It still needs to have a dark, smoky quality. And this was the perfect cymbal. In some songs, I tried five, six, seven ride cymbals, and I always came back to this one, so I cut it with this one.

MPc: Did you mix up your stick choice as well?

GH: Well, yeah, I tried playing with a lighter stick, and actually it didn't sound as good as playing with my heavy stick, my Vic Firth signature stick, which is quite a big, heavy stick. And I thought, well, maybe that's going to be too dominant and it's going to produce too much volume in the cymbals, but actually I recorded—I tried it with a lighter stick, and when the band's really smoking, it's like, oh, I can't hear the ride cymbal. And I went back and did some with a heavier stick, and I thought, actually, that's what I need.

MPc: Well known to your musician followers, you purpose built your drum room to facilitate recording. One of the things that I immediately noticed in the various photos and videos is that you chose to close mic all of your drums. Can you tell me a little bit about your approach to miking the drum kit?

GH: Well, it's a modern approach. Of course you can always just start with the overheads and then fill in the gaps, but actually in modern recordings where everything's poking through so clearly, that kind of approach with the overheads plus a bass drum mic didn't give me the sort of articulation and detail that I wanted.

So, I do go for close miking. I use a lot of AKG mics. I use 414s on the toms. I've got a pair of AKG C12s as overheads. But they're kind of behind me. They're like an extension of where my ears are. They're about, I don't know, eight, nine inches behind my head, but they're spaced like they're—they're like a sort of extension of what I'm hearing from where I'm sitting. Rather than have the mics over the cymbals, which is more normal, this really captures all the cymbals and the drums together.

And with these particular mics, you've got variable patterns, so you can have it hyper cardioid or you can actually open it up to omni. There's about nine steps in between. And as you open it up, you start to hear more of the room, you start to hear more of the drums. Any drum sound, especially in a drum kit, is a very complex thing because… What am I recording? About sixteen mics are hearing everything I play. So, when I hit the snare drum, of course it's going down the snare drum mic, but it's also going down all the tom mics and the hi-hat mic and the overheads and the big room mics, are all hearing the snare drum to different degrees. So, you've got to get a little bit careful with the phase and you need to experiment, which is great having a studio at home, experiment with the mic placement and the phase settings.

MPc: What mic do you use on your kick drum?

GH: I've got a D12VR, AKG, their newest version of the classic D12 bass drum mic. But it's got some switchable patterns in it—the old one didn't have that. And I use that in tandem with an [Shure] SM91A, so the two of them are suspended inside the bass drum in the middle of the drum. I blend the two of those together.

MPc: After you record, do you go ahead and remove all of that bleed from adjacent drum tracks to the—?

GH: God, no! That's the sound of the drum kit. When I hit the snare drum, all the toms ring. That's what a drum kit sounds like. I hate it when mix engineers start trying to get rid of all the tom spill because that's not what it's like. It's like if you play a note on a piano, if you go and hit Middle C, you'll hear Middle C but you'll also hear the rest of the piano ringing. Now, if you're wanting to sample that Middle C, you wouldn't go and get a load of towels and blankets and put them over all the strings except that Middle C, the strings that are associated with that Middle C. It would sound terrible. It would sound like a dreadful, cheap soundboard.

So, the drum kit is an instrument. It's not like the bass drum's one instrument, the snare drum's another instrument, the ten-inch tom is another instrument, the cymbal is another instrument. It's all making a sound all the time. The cymbals are ringing even when I'm not hitting them. All the mics are hearing everything.

So, you just need to be really careful about how you mic up the drums and how you deal with it. I know lots of mix engineers are wanting these gates and they want to close down certain… I'm not from that school of thought process. Because if you're a drummer, you know what a drum kit sounds like. The worst thing is when a mix engineer who isn't a drummer tries to make the drum kit sound the way they want it to sound, and it doesn't sound like that.

“If I wanted it quiet, I'd have just hit it less hard. I play the mix.”

So, I get pretty annoyed when engineers mix my kit because they nearly always dis-balance the way that I played it. I know how I played it. I know how hard I hit the right cymbal or how hard I hit the snare drum, so there's no point in trying to turn it down. If I wanted it quiet, I'd have just hit it less hard. I play the mix.

You know, if you want a great drum sound, you've got to play the drums great. You've got to make that sound with your sticks. And you mix all the elements of the kit as you play it. You just need to put the faders all in a row, and it should be how I played it. I don't want some guy turning the bass drum up. Well, I didn't hit it that hard. You know what I mean?

MPc: Sure. I've noticed you do all of your playing it seems these days with in-ear monitors.

GH: Yeah.

MPc: In-ear monitors are oftentimes pretty challenging for capturing low frequencies, so I'm curious which ones you rely on and if you supplement them with a ButtKicker or other solution for the low end.

GH: Yeah, I've got a really good solution. It's called the Porter & Davies BC2 Tactile Monitor System. And basically, it's primarily for the bass drum, and you're sitting on the tactile monitor. It's built into the stool. And, it's the only one of those—let's say—ButtKicker sort of things that I've ever tried that didn't have a delay. Because I've tried some of those stool shaker things, and I could tell there was let's say ten milliseconds of delay, and it drove me crazy. It has to be absolutely instant. And the Porter & Davies one is the only one that I've ever tried that feels absolutely instant to me.

The in-ear monitors, I can't really play without some kind of in-ear monitor now because my tinnitus is so bad. If I got on the drums with no ear protection and played for 20 minutes, my ears would be ringing for a week. They're already pretty bad. I've got loud whistling all the time, day and night, and that's thanks to my very loud, unprotected playing going back 30 years, doing, I don't know, tours with Iggy Pop and having no ear protection in and just smashing the hell out of the drums, having the drums through the monitors. The bass was so loud my eyes were vibrating in their liquid. Yeah, I'm not kidding.

You know, it wasn't just that gig; it was loads of gigs. And starting to do tours where they wanted you to play to tracks and having click tracks in your ears really, really, really loud. I mean, just blowing your ears apart. So, now, I've got to be really careful. I don't practice the drums unless I've got in-ear monitors in.

I've got two types. The ones that are most convenient to get in and out are the Ultimate Ears. I've got UE10s that I bought about five years ago. They're hard plastic, and you can push those in and out really quick. But they move. Because they're hard plastic, if you open your jaw or you grit your teeth or you move your head or you're sweating, these things move all the time. And it's also fair to say after five years, my ears have changed shape, so I've got to get some more made.

The other type that I use, which I use on stage, are Sensaphonics, and they're called 3D Ambient. The great fun about those are they're made from soft silicone, which are harder to get in and they take about a minute before you really get them right inside, and they go right past the second bend. They go a long way down into your ear. But if you're going to do a 2.5-hour concert, they are much more comfortable because they're soft silicone. They move when your ear canal changes shape or you move your head or you open your mouth or you smile or something; you can feel that they haven't shifted.

And the other thing about the 3D Ambient Sensaphonics is that they've got mics built into the outside of them, so you can have conversations and you can dial in varying amounts of those mics that are on the outside of the ear pieces, or have them off if you want to go totally closed.

MPc: I totally know what you mean… if you just—if you move your jaw a certain way, suddenly a gap opens in your ear.

GH: And that's horrible. And then you find yourself pushing them in. They're very convenient on a day-to-day basis. When I'm sitting in my studio, I might put them in and out 20 times in a day. It's quite difficult to put the other ones in and out. It takes a long time to get them in, and it's not easy to get them out quickly. And it probably doesn't do them a lot of good. You're in danger of tearing them or damaging them if you're going to push them in and out of your ears 20 times because they're soft silicone.

But the hard plastic ones, like the Ultimate Ears, your ear has to shape around it. It takes 30, 40 seconds before they start to feel like they're really in. But as you know, the block or the seal is where all the bass end comes in, and if you break that seal by moving your jaw or moving your head, then you're all over the place on stage. It's just not enjoyable.

The Sensaphonics really sound very, very good, but they take a lot of care and attention. I have to use a special electric box that's got a dehumidifier in it because you've really got to get all the moisture out of these things or you'll destroy the mics. And it needs a nine-volt battery every day. So, it's quite a lot more care and attention needed to use the Sensaphonics. If the batteries go dead, you haven't got any sound at all, so I started having a box of rechargeable nine-volt batteries and I've got a spare one on stage with me in case it goes. It never has, but just in case.

MPc: Looking at your back catalog, what's your favorite album that you recorded with Porcupine Tree?

GH: Hmmm. I guess I liked Deadwing. I think there's some good songs on that and some good, fun things to play. I liked… In Absentia was good, but probably Deadwing. And Nil Recurring, I really liked. It was a four-track EP that came around the time of [Fear of a] Blank Planet. There's some really good stuff on that. We got pretty experimental.

MPc: When you became part of Porcupine Tree and the band started getting larger and larger, did you envision that it was going to have a finite lifespan and that it would just sort of be put on hold when it did?

GH: No. No. And I don't think any of us did. When we finished touring in 2010, we all really wanted to have a decent break because we'd been touring for fourteen months at that point. And every tour had got bigger and longer and more involved, and so we felt like we wanted to have a big break after that last gig in 2010. It just got bigger and bigger.

MPc: Have you ever considered doing a new project with some of the guys without Steven [Wilson], just based on your history of making that music together?

GH: Not really, no. All of us have been busy. Obviously Steve's been busy doing his solo stuff. And Richard and Colin and myself. I've done three albums and three tours with O5Ric, and I've joined King Crimson again. I couldn't really fit it in even if it suddenly reappeared tomorrow. It would need very careful planning if we were ever to do it again. It would need careful planning for the four of us to find the time where we're all mutually available.

MPc: Sure. Now that the jazz record is behind you, what's coming up?

GH: Well, I've already started working on the rehearsals of the next King Crimson tour. King Crimson, there's three drummers now, and we've already done a week's work at my studio where Pat Mastelotto and Bill Rieflin came over. And we've been working on other songs, new songs, new drum performance pieces. It takes a really long time and careful arranging to have three drummers play together and have it not sound like total chaos.

To find really good drum parts and choreograph them across the three drum kits, that's very time consuming. And before we start rehearsing with the band, we're going to get together for another maybe nine, ten days—just the three drummers, and carry on working. We can play to backing tracks, multi-track recordings that we've got. Some of them are just demo things, but at least we're playing along to the song and we know where we are, so we can arrange the drum parts. So, although the Crimson tour is not going to start until the very end of August, there's a lot of work to do before that.

Interview and Forward by Scott Kahn

Photos by Bob Wiczling