Excerpt from the book, The Storyteller's Dilemma: Overcoming The Challenges In The Digital Media Age

By: Louis Hernandez, Jr., Chairman & CEO of Avid

• THE FORCES DRIVING THE INDUSTRY TODAY

• THE DILEMMA FACING MEDIA COMPANIES

• THE FALLOUT: MONEY RISES TO THE TOP

• THE SLOW DEATH OF GREAT CONTENT

The extraordinary difficulty of competing in the current environment has driven media companies in directions that they never anticipated. They must produce more content than ever before and support more distribution choices in addition to their existing infrastructure and business models, but their budgets aren’t growing fast enough because revenues can’t keep up with new business requirements.

THE FORCES DRIVING THE INDUSTRY TODAY

Several large-scale trends are having a dramatic and ongoing impact on the economics of the media business. These are creating powerful driving forces and barriers for media companies across the spectrum, from music to film to broadcast, gaming, and beyond.

Trend #1: Concentration of Consumer Choice

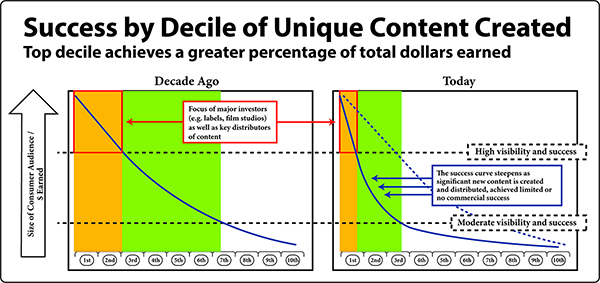

More choices have led to more concentrated consumption, not less as might be expected. Over the long term, that has a corrosive effect. Concentration at the top means that the money goes to those most likely to succeed. That in turn means fewer artists will make it, and those that try to break through will earn less unless they’re at the very top. This will eventually lead to lower quality and less choice of new content.

That’s not the way it was supposed to be. Earlier, we discussed the mass customization concept: in theory, if we could just digitize all existing and new content and distribute it according to consumer preference, we would see a lower concentration of content consumption. More choice should lead to broader consumption (and more revenue) because companies could track and readily respond to consumer tastes even if they didn’t match what was most popular.

The logic was that the major labels, production studios, and media houses that controlled distribution and intellectual property rights would no longer need to work as hard to drive demand. Without customization, consumers didn’t have a low-cost way to consume what they wanted when they wanted. People either watched and listened to the choices that the industry created for them, or they would have to go on a long, strange hunt for esoteric titles in the odd music store, club, indie film festival, or art house. Mass customization would supposedly make that unnecessary and allow consumers to find all that they love with ease.

But in fact, the digitization of content has had the opposite effect. As choice proliferated, it became overwhelming, and unless people were intensely interested and engaged, they couldn’t afford the time and effort to filter the dramatic increase in choices. As noted earlier, the result is that consumers look for filters to decide what to watch or listen to; the taste of others trumps that much-vaunted personal tailoring.

Companies making selections for us using proven techniques for identifying the “best” actors, directors, musicians, and stories turned out to have real value. They fill the role of trusted brands that can help us decide what’s worth consuming. In addition, digitization and connectivity tools have allowed consumers to more easily understand what is most popular, as consumption patterns create a crowd consensus: rather than filter ourselves, we gravitate toward the most popular movies, TV shows, and music. As a result, there is actually more concentration, not less, despite a dramatic increase in choice.

Trend #2: Shift in Investments to Distribution and Monetization

At the same time as there is more concentration and rapid increases in both content creation and consumption, there’s been a much more dramatic proliferation of digital formats, channels and devices through which to consume content. In order for the industry to adapt, compete, and maintain stable profits, significant investment in these newer models is necessary. That money must come from somewhere else.

That’s forced a large-scale shift in budgets to support these areas. The good news is that these new ways of connecting give the media industry access to a larger audience all around the world. The bad news is, the revenue from new digital channels is much lower than that obtained from broadcast and other traditional forms of distribution. Making matters worse is the emphasis by digital-only media disruptors on consumer acquisition rather than the profit that will eventually be required to maintain the distribution channel. Media companies must choose where to spend their limited money in the face of this reality.

As a result, while the importance of creating better content is recognized, there is greater pressure to monetize that content and support all these new channels and platforms. Even if media companies wanted to hold on as long as they could to traditional distribution channels where profits are greater, they couldn’t. Depending on the geographic region, consumers have an increasing number of alternative content and consumption choices, and little reason to stay with the old channels.

To participate in the marketplace, media companies either need to adapt by offering similar distribution options or risk being reduced to irrelevancy. As this painful and delicate transition away from the old model advances, companies must manage a complicated shift from the tools, infrastructure, organization, and people dedicated to traditional channels toward a profile that better supports the new model. This naturally moves money away from creative tools to the distribution and monetization tools.

Think about it. There is more pressure than ever to both create more at a lower cost and automate the entire media workflow. If you have a small increase in overall spending, and new digital distribution and monetization tool investment is growing at a much faster rate, something has to give. Usu- ally, it’s creative and infrastructure budgets, along with investment in more established and profitable distribution models, that suffer.

Trend #3: Lack of Tools to Support New Business Models

Many of the companies that support the media industry face the same dilemma as their customers. Walk the halls of industry trade shows and events, and it’s easy to see. Many software, hardware, and service providers created tools for a different time and a different place, and they have found it difficult to move beyond those legacy investments.

The media technology landscape is littered with too many vendors chasing too few dollars, with proprietary, siloed tools designed for a time when business models were different. Some romantically hold on to the past, hoping that someday we’ll return to a simpler time in which a series of disconnected tools still works and can be supported by what is now an outdated economic model. New applications to replace these technologies don’t need to come from the same players, or even be hardware-based; media companies can, in many cases, simply move to pure-play online providers. But the marketplace has yet to mature.

Today, most legacy tools are ill-suited for the digital reality that is upon us, and gone are the days of creating new products that only work in proprietary formats that make it costly and difficult to connect. The situation has reached a boiling point, and the industry has been forced to turn to unproven, early-stage technologies that don’t scale and lack the ability to deal with the complexity of the industry. Eventually, these tools will give way to a more efficient and collaborative approach to media production, but we’re not there yet.The movement of resources from content creation to monetization is made worse by the fact that new digital distribution models, such as streaming, are less mature and less profitable. And there are more of them, requiring media companies to spread budgets more thinly.

THE DILEMMA FACING MEDIA COMPANIES

While the transition to a more digitized world is occurring, media companies must continue to compete and win. Some of their challenges date back to the origin of the media business itself—content, for example, is still king. But there are many new issues to contend with.

The business imperatives that media companies face as they shift to increasingly digital business models are multifaceted but on the whole straightforward. These enterprises must:

- Create great content—Over the past decade, the broader availability of low-cost, high-quality professional tools has allowed many more people to tell their story. However, the dramatic rise in content has also made it harder to be heard, putting additional pressure on creating the very best content. Whether it’s a better news story to inform, a scripted show or game to entertain, a major motion picture, or professional music meant to inspire, the competition to be heard is more severe than ever. The need to work efficiently with the best talent anywhere in the world to create the best sound or story has intensified.

- Make the content available to more channels and devices—Rising even faster than the volume of content itself is the number of ways in which audiences expect to consume it. Stories can (and need to) be found via traditional outlets, such as movie theaters, broadcast networks, radio, or downloaded files, but increasingly that content must be made available in multiple formats, on a wide variety of devices and digital channels, each with varying data structures, requiring greater investment for the same piece of content to reach the audience. As expectations rise for greater choice on how people consume content, the cost and com- plexity of distribution has gone up. The industry now has more ways to connect with almost every community on the planet; however, the economic model for sustaining these formats has yet to prove itself.

- Optimize the lifetime value of the content—While many artists create content for the joy of being heard, economically supporting that passion has become more complicated than ever. If media companies find the winner that connects with audiences, they must work harder to optimize the value so that they can continue to sustain bringing more content to the market. This means making sure that any part of the content can be reused easily, that it can be accessed anytime anywhere quickly and inexpensively, that the rights to different parts of the content can be identified and used easily, that it can be made available in multiple formats at a low cost, and that it can be avail- able immediately at any time. Optimizing lifetime value also means more intimate, more intense, and longer engagement with audiences; it’s the human connection that drives consumption. Here, immersive storytelling is playing an increasing role, starting with gaming, concerts, and sporting events.

- Do everything more efficiently—As described earlier, although the overall spending is increasing, it’s not keeping pace with the amount of content and distribution channels that consumers expect to enjoy. In addition, the shift to digital channels and economic models is putting tremendous pressure on the workflow of media operations. No matter where or how you participate, you’re feeling increasing pressure to do more with less. The hunger for new technologies to connect all the pieces, make production more efficient, and integrate processes is accelerating.

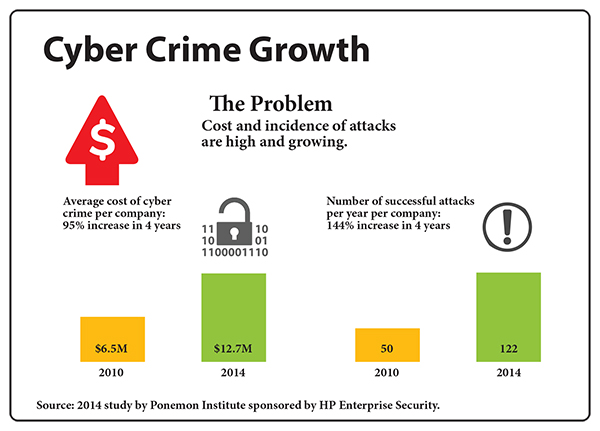

- Make it secure—Security has always been a concern, but today it’s becoming an even larger issue. Just as in other industries and in our personal lives, as we increasingly rely on digital connections we are exposed to new security issues. These security concerns vary widely. News organizations and their networks that want to get the story out as quickly and easily as possible are prime targets for certain groups ready and able to cause harm because they don’t like the stories, or want to find out who is writing them, or track down the sources for retaliation. Once off-limits, journalists are now at great risk; in 2013, 66 were murdered around the world, and in 2014, 137 were abducted, with many still held years later.1 Major film studios want to ensure that the next blockbuster doesn’t get released to the public in an uncontrolled way, placing substantial ticket revenue and other mone- tary opportunities at risk. Without those revenue sources, the studios couldn’t sustain creating new stories and bringing them to market. For a music company or individual artist, piracy represents a direct and fundamental threat to their livelihood. Every illicit track download or unrecognized playback royalty is a straight loss.

THE FALLOUT: MONEY RISES TO THE TOP

Since consumer consumption patterns have led to greater concentration, those that win, win big, and they’re making it harder for unrecognized artists to make it.

It took some time for this concentration to take place. Early in the shift toward digitization the industry took a portfolio approach. There was more content variety, with a mix of smaller, unknown, indie-related projects bal- anced by some large “tent pole” projects. That model has eroded, as the con- sumption patterns have shifted to proven stories and storytellers. As a result, the smaller projects are being crowded out by larger projects from proven players to ensure they are on the right end of the content consumption curve.

Media companies, finding that the “long tail” of available content has less value due to tighter concentration, have been forced to focus their investments. The result is more hurdles for anyone trying to break into the business.

It takes so much money and effort to get attention in an environment of endless choice that for every Taylor Swift or Beyoncé, there are myriad tal- ented storytellers who cannot get any traction because the smartest move for a media company is to reduce risk by supporting a known success.

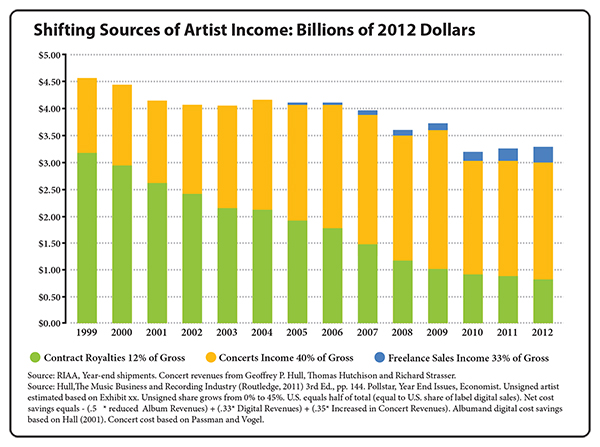

At the same time, the increasing adoption of low-margin digital channels makes participation in the marketplace less profitable for content creators. To make matters worse, in some segments piracy is still a major issue, which further damages their ability to make a living. The biggest losers are the indi- vidual artists—although everyone loses when content is stolen. Content creators obviously lose because they’re not being compensated for their hard work. Media companies lose because there’s less money to invest in new, high-quality content and better customer experiences. Consumers lose too, because they’re not supporting the storytellers that create the content they love, and without that support those artists may have to leave the stage.

This combination of greater concentration in the face of more choices and the increased use of less profitable digital channels has had a significant nega- tive impact on traditional media companies and the content creators who rely on them. The biggest winners in the game are digital distributors and digital channel providers who aren’t burdened with the legacy models and infrastruc- ture that the older companies must support. As we’ve seen with the evolution of the World Wide Web, there is a higher value potential placed on digital channels. In the dot-com bust, many of the early pioneers came crashing down and never recovered when their funding dried up and profits were nonexistent.

Forward-looking digital distributors in this wave recognize this and are moving into the content creation side. Nontraditional players like Netflix are producing some of the best programming. When the dust settles, those that get it right are positioned to become media powerhouses in their own right.

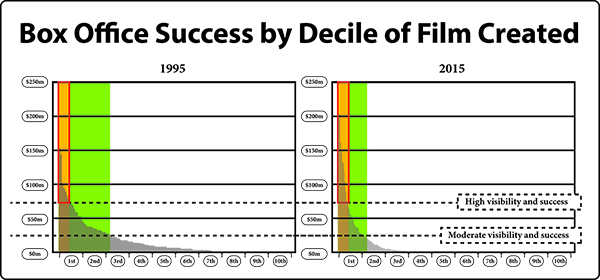

This fallout from concentration is reflected in the real world. Take a look at box-office success for new movies over the past twenty years. Earlier we observed that even as content proliferates, audiences driven by mass-market appeal tend to focus on less of what’s out there. The data proves this out.

At the left end of the charts are the most successful and popular movies of the year. In 1995, 37 percent of the movies released made up 90 percent of total gross domestic revenue. By 2015, a much smaller percentage was likely to achieve the same; in that year, only 12 percent of all movies released gen- erated 90 percent of total gross domestic revenue.

Put another way, in 1995, 90 percent of box office proceeds came from 37 percent of the movies in distribution. In 2015, 12 percent of the movies in distribution accounted for 90 percent of revenue. In short, only the biggest hits are drawing audiences today.

What does this mean for a movie studio? To make any money, all the backing has to go to blockbusters that stand a reasonable chance of filling theater seats during those critical first few weekends. It’s not only the initial box office that matters; the incremental revenue from a known and successful movie once the film is out of theaters is substantially higher. The so-called smaller or indie films are less profitable over both the short and long term. So, even though more of these movies are being made, less funding is available to make them successful, and they’re less likely to be distributed nationwide. There’s a reason why all the theaters in a given area seem to be showing the same movies, and this is it.

That’s bad news for up-and-coming filmmakers, who may find a warm reception and great success at film festivals like Sundance or Cannes but are unable to break through to become commercially viable. The economic incentive to take a chance is low, making for intense competition for funding. For moviegoers, it means that there’s actually less choice of new content that might make it worthwhile to spend money on a movie ticket. By the third weekend, there are likely to be only a handful of patrons in any given showing, and the film won’t be in theaters for very long, if it ever makes it to the multiplex at all.

A similar situation holds for TV. According to media blog REDEF, in 2000, approximately 90 percent of original scripted television series made it to a second season. By 2014, that number was about 50 percent.4 That’s despite a compound annual growth rate of 14 percent in scripted TV series over the past five years.

There’s a lot more churn now, as networks concentrate on more successful shows and are very quick to pull the plug on those with low ratings. In 2015, CBS canceled Angel from Hell after only five episodes had aired. Meanwhile, evergreen franchises like Survivor and NCIS are renewed year after year and spawn multiple spin-off series. This is an example of how media companies, n the never-ending drive to keep revenue flowing, act conservatively and devote their resources to proven properties. There’s not much appetite for risk, so the formula is followed. That makes it harder for truly new ideas to find their way to audiences.

The music industry is no different. According to 2013’s Next Big Sound State of the Industry Report, more than 90 percent of all artists are undiscovered, and popularity is proportional to exposure—in other words, the larger the following already is, the more new followers the artist will gain.6 Only 1 percent or so of artists rise to “mainstream” or “mega” status, and roughly 80 percent of the artists that the report tracked got less than one Facebook page like per day. Without support, it’s almost impossible to get a break. But once again, look at it from the point of view of the record label. Where is the best place to put your money?

It’s a situation worthy of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. There’s more content than ever, more consumption than ever, more choices in how to discover and consume new material . . . yet more focus on a few mega-hits than ever, which will ultimately lead to less variety, as those who can’t see the light of day leave the game entirely.

THE SLOW DEATH OF GREAT CONTENT

There’s one statistic that I find especially troubling. In 2015, streaming of existing songs (“catalog” content) outstripped new music for the first time, and only 30 percent of the traffic was newmaterial, according to Billboard. Much of this can be attributed to the shift away from downloaded content. On-demand streaming makes it easier and less expensive for consumers to access the full catalog without having to make an additional purchase. In other words, as purchases fall and streaming increases, new music is losing market share.

But in my view, it’s not just about the shift in distribution model. It’s also a reflection of something deeper and more disturbing. People are consuming more catalog content because they aren’t finding value in new content—they prefer material they already know.

After all, the same streaming service can deliver new content as readily as catalog content, so there must be a reason why the traditional 50/50 split between catalog and new releases is changing. In short, from the consumer’s perspective, the quality of new content is not up to the standards of what came before. It’s beginning to look like the corrosive effect of low investment in content creation is starting to appear. By concentrating on the top end, media companies are allowing up-and-coming talent to wither on the vine. Consumers simply are not able to find and enjoy new content with which they truly connect. The exceptions, of course, are the blockbuster hits from major artists that we all know and love. These are the properties that media companies pour resources into.

Part of the problem is that in the current environment, new artists have a harder time establishing and developing their careers. There have always been one-hit wonders, but today even truly talented acts have tremendous difficulty gaining traction and may disappear before the public has a real chance to discover them. This is an unintended consequence of the 40 per- cent reduction in artist pay that’s occurred as distribution models have shifted to digital and streaming and budgets have gone to monetization of proven properties. The crushingly low level of compensation forces artists to make decisions earlier about whether they can make a sustainable living doing what they love. Many play just to be heard, but at some point, eco- nomic reality sets in and they’re forced to move on.

In the short term, the industry has been riding a wave of technological change that’s supported consumption, from physical formats to digital, and from download to streaming. The growth bet right now is on improving the streaming experience, but the revenue model isn’t working very well yet, especially for the artists. Streaming margins are so thin that a major industry shake-up is in the offing; although enterprise values can be high, the eco- nomics are unproven.

More important over the long term, however, is the quality issue. Eventu- ally the failure to invest sufficiently in the next generation of content is going to come home to roost. For media companies, the shift in interest toward older material is a warning sign—broaden the base, invest in quality content, and make it worthwhile to be a storyteller, or face a future of shrinking reve- nue and market share.

To purchase a copy of the book, click here.