You can’t talk about pop rock from the ‘80s without referencing The Outfield’s multi-platinum hit, “Your Love,” penned by a British group that was actually far better known in the United States than in their native UK. Founded by bassist/lead singer Tony Lewis, guitarist John Spinks, and drummer Alan Jackman, their debut multi-platinum record laid the groundwork for what would become decades worth of melodic rock records and numerous additional hits.

You can’t talk about pop rock from the ‘80s without referencing The Outfield’s multi-platinum hit, “Your Love,” penned by a British group that was actually far better known in the United States than in their native UK. Founded by bassist/lead singer Tony Lewis, guitarist John Spinks, and drummer Alan Jackman, their debut multi-platinum record laid the groundwork for what would become decades worth of melodic rock records and numerous additional hits.

The music of The Outfield has an immediately recognizable sound due to the unmistakable vocal work Tony Lewis, his driving bass lines, lush synthesizer textures, and guitar tones that ran the gamut from classic rock to bouncy, syncopated delay lines that were, well, unmistakably The Outfield. Over the years, other supporting musicians came and went, but the core songwriting partnership of Lewis and Spinks remained for their entire career up until Spinks’ untimely passing in 2014.

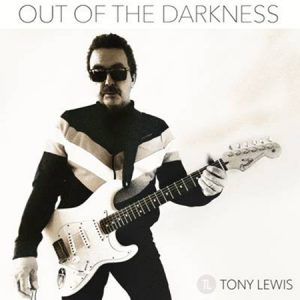

Lewis retired from music with the passing of his longtime friend and bandmate, but a few years later, the insatiable need to create art re-emerged, which led to Tony’s first solo release in the Summer of 2018, the aptly titled, Out of the Darkness (read our review here). We spent some time talking with Lewis about the new record as well as taking a walk down memory lane.

I wasn’t just the singer and the bass player of the Outfield.

MPc: Out of the Darkness, sounds very much like classic Outfield. But the first thing that blows me away is your voice! So many singers lose their high-pitched voices over the decades, but you haven’t. What’s your secret?

TL: I don’t know. Goggling beer every night, I think, I don’t know. [laughs] I loved Robert Plant and I’m still staggered how high he used to sing on certain albums and you see him now, he doesn’t need to scream that high. But he’s still good. I think I’ve just been lucky, really. I’ve got no real sort of tips. I don’t really do all the vocal warmups and honey and steam and stuff like that. I just get out there and just do it. I’m just lucky, I suppose.

MPc: Did you have any particular theme in mind when writing Out of the Darkness? Or is it just a random collection of songs?

TL: Out of the Darkness, it’s basically, the whole concept is a venture back into the music industry after quite a four-year hiatus. Losing John and that, the first two years, I didn’t even like music, I didn’t want to pick up a guitar. Music for me, I just lost all sort of—lost the plot, really, with my direction.

Now, my wife said, why don’t you just do what you do best? She said, you can record, you can sing, you can do anything you want. So I started recording. Did some backing tracks. And I struggled with the lyrics. I was being soft. I think the first song I wrote was like, “I’m going out for a fight” or some other thing. People are not going to relate to that. You don’t want to go out and fight.

She said, I’ve got some words, here, I put together, what do you think? Should we try this? “Here and Now” and “Into the Light” were the first two songs. I wanted to keep the Outfield stamp. I wanted to keep that sort of… the big intros. On radio, you can’t have long intros because people just either dial out or they just lose interest. So, “Into the Light” and “Here and Now,” I wanted to make them Outfield (sort of) classic choruses, but I wanted my verses to be—add my twist on it. And the bridges would have my twist on it. And somehow the lyrics that she wrote worked.

But it all just, it came together over a period of two years and it was such an easy way of recording. There was no stress. I just loved doing it. When I hear people saying it was a big undertaking, taking on a solo career, getting the musicians in and that, I just basically did all the instruments myself and just took my time and just crafted out one song at a time. And it’s been quite a pleasurable process doing the album.

I’ve got quite a few basses, but the bass that I get the best tone out of is the Steinberger.

MPc: So, you played everything on this record. How did you go about achieving the classic Outfield sound with you playing everything?

TL: I always took a big part in the production and I did keyboards, I sequenced drums, because… in ’89, Alan left the band because he was a bit taken back by digital drums, drum machines, he wasn’t a big fan of that. For me, it was like—well, not the way forward, it was just another avenue to go down. If we could program songs, you didn’t have to hire big drum rooms to put a song together, because we were using small rooms.

So I just learned how to do drums, learned how to do keyboard sequencing. I played guitar sometimes and John would play bass. There was no ego there. Who’s that playing bass? Who’s that playing guitar?

So we sort of shared the instruments, from Diamond Days, Rockeye, them albums. I’ve always done drums and always done keyboards and guitar. I like playing guitar more than I do bass, to be honest, even though I’m the bass player. Because, yeah, I just love chords and I love effects. And just the tone the guitar makes, it’s just magical.

So this album was to sort of prove to people that I wasn’t just the singer and the bass player of the Outfield. I’ve got more strings to my bow. Just wanted to show, basically, step into the light, and this is me. This is what I’ve done, and I hope you like it.

MPc: Would you mind sharing a little bit about the guitars and basses that you used on the record?

TL: To be honest with you, I’ve got quite a few basses, but the bass that I get the best tone out of is the Steinberger. Because I love the EMG pickups. I’ve got one of the real old ones, ’87 Steinberger. And for recording, I also picked up a 4003 Rickenbacker a few months ago. And that’s an outstanding guitar. But, to be honest with you, I did most of the bass tracks with the Steinberger.

For the guitars, I’ve got a Fender Standard Strat. And I’ve got a Telecaster American Elite. I’ve also got a Gibson SG bass, which I played on a couple of the tracks, because I love the different tone it makes. But the majority of the pumpin’, chuggin’, Outfield-type bass patterns, I’ve been using the Steinberger.

MPc: I can’t fault that. Half the bassists I know own at least one classic Steinberger bass.

TL: Yeah, they’re great…

And I love Mesa/Boogie amps, as well. I’ve got, actually a Dual Rectifier combo. For guitar, there is just a huge, monster sound and I love that amp. I use a little Fender Champ, as well. Sometimes put the bass through that.

I’ve used Logic Pro for the software. And it’s a great songwriting software, it really is. You can get all the keyboards and different drums and stuff from it.

MPc: So were most of your drum and keyboard sounds from Logic?

TL: Yeah. I use a Roland kit and EZDrummer 2 for my kit. I just use one kit. I just—I use one primary kit and I just change the EQs depending what track I’m doing. Or I might use an old Tama Motown kit for about—you know, on “The Dance of Love” on the album? That’s a Tama Motown kit. Because I want to get the sound like a real old-school drum kit, rather than a fresh Black Beauty snare or Drum Workshop drum kit. I wanted to sound like an old kit.

And it wouldn’t take me too long—if I don’t dial up a sound within two or three minutes, I get impatient and I just shut the computer down. Because sometimes, new technology, you can spend hours and hours and hours and hours, because you’ve got libraries of sounds and you don’t actually get anything done. Whereas I’ll get a guitar sound out through the Mesa/Boogie. Straight, no effects, just put something to—we still use the term “tape,” but it’s not. It’s hard drive. But “record to tape” sounds better [laughs].

And me and John had been using Pro Tools up through the last album. He liked Pro Tools, Pro Tools is good, but I like Logic because it enables me to write and I can put different colors and stuff. It’s a good songwriting program.

MPc: Did you make the whole record in your home studio or did you go someplace?

TL: Yeah. What I did is I created all the tracks in the home studio and I was lucky enough to—basically, how the deal came around was Randy, Randy Satz, who did promotions, he did work for the Outfield years ago. Obviously he knew of John’s passing and he let me be for a couple of years. And then he sent me an email saying, “You okay?” and I said, “I’m fine.” He said, I’m going to be in London soon. And I met him in London for a drink and he said, what have you been doing? I said, I’ve got some songs, I’ve got some backing tracks together and my wife’s lyrics seem to fit these backing tracks so well. What do you think of this? And he said I think I can help you out here. And he knew Tanner Hendon, who owned Madison Records in Atlanta. And Tanner Hendon is a great drummer, as well. He played with Paul Rodgers of Bad Company.

So, for me to find a company owner who played drums as well was like finding gold. It really was. And I mean, I’ve done some drums on this album, but I really like the feel of a drummer. Could you do some drum tracks? He said, yeah, fine. So he’s playing on five of the songs. And the rest I did myself. He’s a great, solid drummer. He doesn’t do anything too flash and too busy. He just reproduced the parts that I did, but with a real kit.

MPc: Nice.

TL: I sent all the tracks to them and they mixed it on their SSL desk, sent me back mixes and I’d go, Can you push this one? Push the bass up, push that—all the usual stuff. That’s the good thing about having the Internet now, because all those years ago, it was—we used Ampex tape and then we went on to digital, Voices of Babylon. But even then, that was quite sort of prehistoric, the setup we had.

But recording to a computer, it’s just, it’s like a dream come true. It’s no cutting tape or nothing like that.

Our harmonies were so unorthodox that they worked.

MPc: Something that really draws me to the songs you write is your use of vocal harmonies. That’s a real big part of your signature style. How did you develop your backing vocal parts?

TL: We never used to work out the harmonies on the piano or guitar, we just used to—John would do a chorus and I’d go in and harmonize that chorus and try this, try that. Our harmonies were so unorthodox that they worked. Because our scales were so different. His, highest John could sing would be the midrange of my voice. Because he’d go to church and sing carols, they’re way too low for me. So I think David Kahne, who produced Voices of Babylon, he described me as a bit of a freak. I thought it was a compliment. [laughs]

MPc: Very nice. [laughs]

TL: Having an unusually high voice, you know? And John had that sort of buzz saw, John Lennon-type, upper-mid sort of sound to his voice and it just—we’d do about four harmonies and it’d sound like 20 tracks.

MPc: So whose idea was it to write the song, “John Lennon,” from Diamond Days? Since you mentioned him…

TL: John was a big John Lennon fan. [Lennon] was his favorite Beatle. So he just fancied doing something that was like a tribute to him. And it’s something that, it suited his voice.

MPc: Who were some of your musical influences while you were developing as an artist?

TL: Well, from the ‘60s, obviously the Beatles and the Kinks, The Who, Rolling Stones. But then there was the glam rock, which made a big impression on me. I like them. I liked Marc Bolan, T Rex, David Bowie I was a big fan of. And those days, you used to save up, you’d get a job and you’d save up the money and all your money would go on albums, or singles, on vinyl. And obviously in the latter part, Journey made a big impression on me. I liked Thin Lizzy, as well. Went to see them quite a few times.

The very first concert I ever went to was Status Quo, but Status Quo weren’t huge in the U.S. But they were huge in U.K. and Europe. And they could play 12-bar really, really well. You wouldn’t have thought that 12-bar rock would work in a pop sense, but it worked.

I liked the very first Thin Lizzy band, with Eric Bell, the rocker? I mean, I always had a thing about 3-piece bands, anyway, and ZZ Top. Cream. Rush. I like Rush. I like exciting rhythm sections. So we’ve learned a lot from them bands.

MPc: One hallmark of your bass-playing style is that you really tend to drive the Outfield songs a lot with 8th note bass grooves. How did you come to develop your style of play?

TL: I think a lot of it was, obviously, growing up listening to Thin Lizzy, Status Quo, AC/DC, that sort of pumping, driving… whereas in the old days, the bass was always considered the background instrument. But I always looked at a bass like a guitar. You know, how Lemmy used to attack his Rickenbacker. I would play it like Geezer Butler, as well, from Sabbath. He’d play his bass guitar like a rhythm guitar. Because also, if you’re a three-piece band, you’ve got to fill out a lot of sound, so you play harder. And I’ve always liked that driving sound locking into the bass drum.

And Van Halen, as well, there’s another good rhythm section. “Jump,” for instance, that’s very much like, a very Outfield-esque rhythm section there.

MPc: Talk about the songwriting process itself. Do you start with lyrics? Do you start with music? What was typical for the solo record and was it similar to how you wrote in the Outfield?

TL: Well, as I said, after John’s passing, I couldn’t even pick up a guitar for a couple of years and then suddenly just wanted to get back in to record a bass line and some drum tracks and just put a backing track together. But I’d sort of lost my way lyrically. I couldn’t write about anything. My wife said, I can help you out, I’ve got some words here and some really good storylines and stuff. And that seemed to fit the rhythm tracks. Some songs were done with us fitting together and recording to an iPad, with the acoustic, and we’d grow that song from there. Or just keep it stripped down to the nothing, just the acoustic. Because sometimes you can have a good song and because you’ve got 30-40 tracks to use, you don’t have to layer, layer, layer when you’ve got a good song. If you’ve got a good song, you can sing it just with one-two tracks on the vocal and a couple of tracks on the acoustics and it’s there.

So I tended not to, tried not to over-produce. So there’d be no real rules as to how it started. I mean, a couple of weeks ago, I had an idea about, something about “You make me feel alive” or something and I had like a drum thing going in my head and a bass thing going in my head and just put it down and recorded it. And then the wife said, how about this for a verse? How about this for an… I had a hook already. And it just—it’s such an easy way of putting a song together. And enjoyable, as well. Because if you don’t enjoy recording, you shouldn’t do it. Because it just takes me off to somewhere else, to another plateau, it’s just—it’s very good therapy.

MPc: I know you’ve got a tour coming up this summer. Who are the musicians that you’ve put together, assembled for your new band?

TL: I don’t. I mean, I’ve got a backing band from Retro Futura and I sent them some Outfield live recordings, because if you send them just the records, a lot of [the songs] just faded out. It’s important that you know how to end—how to start and how to end the song. I’m going to Atlanta a couple of days before, whatever, rehearsal, get together and I’ll take my bass and we’ll just have a jam and see what happens.

I mean, they’re great players, so I’m looking forward to it. It’s going to be bittersweet. It’s going to be strange not having, looking over to my right and seeing John there, because all these tours, all these years and all these albums, all these countries we’ve toured together, it’s going to be a bit strange the first night, getting on that stage on my own. It’s going to be a bit eerie, but I’m excited. Excited about getting back out there again and doing my own stuff.

“You get a lot of bands that have just got maybe one original member, but they still use the name. I just don’t get that.”

MPc: Excellent. Now, what I’d like to do for the last part of our interview is to revisit the Outfield catalog and I just want you to tell me the first story that pops into your head about each record. It could be anything from songwriting to an experience in the studio to the way you stumbled on a sound. Anything, the first thing that crosses your mind I want to know.

TL: Okay.

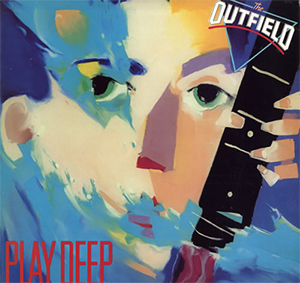

MPc: Let’s start with Play Deep.

TL: Oh, Play Deep. I remember, we recorded in Air Studios in—Air One Studios. We did the drums, and me and John and Adam were in one room. And we were really nervous because, prior to this point, we’d just been doing demos at a local studio. So it was our first real, big studio, so we were, like, the red light’s on, we’ve got to do this properly, you know? And we were freezing cold [laughs]. Remember looking down my fingers and they were blue. I couldn’t even play the bass. I thought, we were paying all this money to play in Air One and I’m freezing cold.

MPc: Well, obviously, it was really well air-conditioned studios. [laughs]

TL: Yeah, it was. It was like—air conditioning in January in England. Think about that one. [laughs]

MPc: That’s awesome. What’s the first thing that pops into your head about making the follow-up record, Bangin?

TL: Well, Bangin, we had to obviously, we were doing it in the same studio again, same producer. But we had to—we didn’t want to get into the—you know that sophomore jinx? You can’t reproduce exactly the same style of playing or sort of songs. So we made it into more of a rock album. And I think we just had a bit more fun on that album, because Play Deep did so well.

I think we took about five months to record that album. And it was just a great, fun period. I’d record a bass track and then John would go upstairs and we had a pool room upstairs, a recreational room. It was almost like an office type of approach to making a record. I remember, you know that ballad, “Alone With You” off Bangin? Brian Adams came past and Bill Whitman used to crank the JVLs so loud, I think he blew up headphone amplifiers. I think he blew up about three of them and blew up speakers. And the door swung open and Brian Adams went past and I think his hair went back. And John said to him, “Don’t worry, it’s only the ballad.”

MPc: Nice.

TL: It was so loud, so loud. I mean, I’ve lost my hearing because of that album.

MPc: Okay, now talk about my personal favorite, Voices of Babylon.

TL: Voices of Babylon, it was actually a turning point, because after we’d done the Play Deep and Bangin, we were sort of—we might have been in danger of being, oh, they’re going to do another Bangin or they’re going to do another Play Deep. So the pressure was on us to make it a little bit more slick, maybe a bit more poppy, a bit more polished. And we did basically half the album in England and the other half in America, the first couple of weeks, couple of months.

Because David Kahne was basically the producer and he was an interesting character. Yeah, Voices of Babylon, I remember doing—when we first recorded the guitars on “Voices of Babylon” (the song), the engineer said that, let’s just get the part down and we’ll add the effects later. I said, no, no, let’s get the sound in the speakers now and let’s just record it. Because, especially the way I record now, the magic has to come out of the speakers from day one. You don’t just play a part and then think, I’ll just add some fairy dust to it, we’ll add some EQ to it. No, get the magic done now. And that’s how “Voices of Babylon” happened, that came about.

The big, jangling, chiming guitars. I think that’s a Rockman and a Lexicon. And that’s how that sound came about. It was just a spontaneous recording, having good fun.

MPc: Next, we enter the ‘90s and have Diamond Days.

TL: Diamond Days, we were able to record up in a north part of England, up in Ipswich, and the album was great because it just had a—I think we called it like a songsmith album, because we didn’t really have to prove anything anymore, with the big, chugging guitars. We just wanted Diamond Days about songs. That’s how actually “You” came about. Just enjoyed that album.

MPc: What about Rock Eye?

TL: Rock Eye, we wanted—we didn’t want to rest back on our laurels, but we wanted to—because a lot of people were thinking, well, have they taken their foot off the gas? This is not the Outfield album that we were expecting. So that’s how “Closer to Me” came about. “Close to Me,” the first single off Rock Eye. I think that made Top 40. And that chorus is the epitome of an Outfield chorus and Outfield sound for me. And we had fun doing the video, as well.

MPc: What about It Ain’t Over?

TL: It Ain’t Over was basically just a sort of—because we got into Pro Tools—we were talking about before, our disc going—we were just flying around all sorts of ideas and stuff to each other. And I’d go to John’s house and record to a vocal a couple of times a week. And every song sounded like it had a different style to it. So there’s some good songs on there. Very good album.

MPc: What comes to mind when you think about Extra Innings?

TL: Well, Extra Innings, it’s basically, 11 songs from It Ain’t Over are on Extra Innings, and it’s 15 songs on Extra Innings, right?

MPc: Yeah.

TL: So basically, it’s just another… I don’t know why we did that. [laughs] But we had a song on Extra Innings called “Heaven’s Little Angel” and that was a great little song. Yeah, it’s basically a lot of songs that we’d recorded over a long timeframe, from like ’91, ’92, fall ’95-’96. So it’s a great album, it really is, it’s a great album. I think it was, Extra Innings was probably a better album than It Ain’t Over, but It Ain’t Over was probably more of a statement that we weren’t going away. And, yeah, we had a lot of fun doing that album. I think I burnt out two cars during those albums.

MPc: Wow. And then you had a big gap timewise from 1999 until 2006 when you came back with Any Time Now, which I really liked.

TL: I remember doing—I remember someone said, “I like the drums on ‘No Fear.’” And I think I did it on a drum machine—that drum machine that was like the size of a box of chocolates [laughs]. They said Simon sounds great on that, “No Fear,” and it was me playing a drum machine.

MPc: Wow. And the final Outfield album, Replay. Tell me something about that.

TL: Well, Replay, we did, me and John recorded all the album and I took a big role in doing the drums on the computer. And I said what’s really missing is maybe real drums. And John said, why don’t we get Alan, see if he’ll want to do some drums on the album? So yeah, we hired a studio in the East End of London, Limehouse. And we tried, it went from, just give it a try, two or three tracks. And then he ended up recording most of the album on the drums.

And it was this sort of—John was starting to feel a little bit ill at this time, this period. And I think he wanted to make a proper, with the three of us, an Outfield album. You know what I mean? Just before he started feeling ill and—it made sense then.

MPc: Have you considered playing again with Alan and possibly doing a new iteration of The Outfield?

TL: Not really. I just wanted to do this on my own. I just wanted to—I mean, we’re still good friends. He understands I just wanted to do a solo album. Because what I found was that, in a lot of the bands—Genesis, they used to go off, Queen used to go off, and do their own solo projects. And we never did that. And I just wanted to experience what it was like.

And Alan will be the first one to tell you, if I’m doing a drum track with Alan, it just takes forever. When we did Replay, we recorded, like, 20 tracks of drums and John had them all on the hard drive. And he said it took him ages and ages and ages to do it. For me, drums, I just want to—I’ve got my electronic kit and I’m trigging off real samples. That’s pretty much like a—it sounds like a real kit, anyway. I just like doing spontaneous drum tracks. I don’t want to deliberate over—Well, that’s tom #2 in the middle 8 sounds a little bit—it’s ringing a little bit. Or, the high hats could be a bit louder Or could we fix that tom? And it was just, the emphasis was all on drums rather than the songs. So it took the fun away a little bit for me.

So I just wanted to do my own thing, because when John passed away, The Outfield was no more. I’m doing this all on my own. I’m Tony from The Outfield. There is no more Outfield because John passed away. He was the man, you know? A lot of bands, they carry on the band name. You get a lot of bands that have just got maybe one original member, but they still use the name. I just don’t get that, I really don’t. I just wanted to do a solo album and then just take it from there. See where it goes.