Grammy-nominated keyboard player, David Rosenthal, is no ordinary musician. He’s an unsung hero of the keyboard world, currently serving as musical director for Billy Joel’s band, which he has been a part of since 1993. This role is just one small part of his exciting history, though. Yes, he backs up the piano man nightly and is in fact one of only three other people to ever play a recorded piano part on a Billy Joel record (the others being Ray Charles and Richard Tee). But Rosenthal already had a pretty impressive resume by the time Billy Joel came calling.

Rosenthal attended Berklee College of Music, where he became a then-bandmate and lifelong friend of fellow classmate, Steve Vai. It was shortly after graduating that Rosenthal landed his first newsworthy gig: replacing keyboard legend Don Airey in Ritchie Blackmore’s post-Deep Purple band, Rainbow. And following a few years of classic hard rock hit making and touring, he served as the keyboard player on two of the most remarkable world tours of the ‘80s: Cyndi Lauper’s True Colors tour, and Robert Palmer’s Heavy Nova tour.

His friendship with Steve Vai subsequently landed Rosenthal on Vai’s classic record, Passion and Warfare, as well as appearing on the classic Whitesnake record, Slip of the Tongue. And this was followed up by Rosenthal’s personal band of virtuosic players: Red Dawn. Their one album is a melodic rock feast that straddles the line between AOR and prog rock, and you can still pick up copies of the fantastic CD from Rosenthal’s personal website.

Still not convinced that he’s more than simply a piano and organ player? Rosenthal orchestrated Yngwie J. Malmsteen’s Millennium Concerto Suite, and also joined prog rock legends, Happy the Man, for their reunion.

This musician is also a geek when it comes to equipment and the studio (our kind of guy), and Rosenthal has either designed keyboard rigs or done sound design work for an A-list of artists ranging from Bruce Springsteen to Dream Theater (he was even asked to join the band years ago) to Alicia Keys. He also consults on new product design for multiple hardware and software companies, and also finds time to develop and produce new talent like the extraordinary, young musician, Ethan Bortnick.

Paul walked up and sat down at Billy's piano and started playing the intro to 'Let It Be' and we had to play that song with him. Having never played it before. Not only with Billy, but now with Paul McCartney.

Want to know some cool trivia? Rosenthal shares a Guinness Book World Record with some of his former bandmates. During Robert Palmer’s 1988-89 Heavy Nova tour, the band set a world record for performing 56 concerts on 56 consecutive nights in 56 different cities! He also shares in two other cool records courtesy of Billy Joel, though not officially certified by the folks at Guinness—and these records keep growing! The first is for performing in the most consecutive sold-out shows at New York City’s Madison Square Garden (approaching 50 at the time of this writing). Billy Joel’s monthly artist-in-residence continues to sell out every single show, and Rosenthal also shares in Billy Joel’s record for sold-out, non-consecutive, shows at the Garden. After all, the band performed in this famous arena for decades prior to calling it home for the tour that never ends. Nice!

Through it all, Rosenthal remains simply a humble guy from New Jersey, and we had loads of fun exploring his past, present, and future musical endeavors.

Billy Joel

MPc: When you first joined the Billy Joel band, the biggest challenge would have been learning all the parts and matching the recorded sounds. What do you find is the biggest challenge today, playing in the Billy Joel band?

DR: I think the biggest challenge today is keeping all the songs current in my brain when we don't play them sometimes for, literally, years. I have 85 songs programmed now. We choose mostly from a batch of 40 to 50 songs that pretty much always get rotated, some more than others. And obscure ones kind of get selected from that.

But there's these other 30 songs, the really obscure songs, which—we're ready to play them. And he could call them out on any day. And I have to not only remember the song, but remember what I programmed and where's the verse patch and where's the chorus and how did I layer this and that so that I can perform it. And sometimes, with no rehearsal.

It stems all the way back to the preproduction days, not only for this tour but on other tours when I actually created these sounds and did the initial work to really ingrain it into my head such that when the moment might arise that he calls out this song that I haven't played or even thought about in years, that I can pull it out of the air and do it.

MPc: Billy Joel's music spans several decades. Is there a particular album or era among that which is your favorite?

DR: It's hard to pick a favorite. I think there are gems in his music from all three of the decades that it spans, as there are gems in all of the music that came out of those time periods. His albums were always using cutting-edge technology of what was popular in the day that they were made. He was always using whatever synths and recording techniques were current at the times that the records were made. So it's sort of like the whole catalog is somewhat of a time capsule snapshot of those 30-somewhat years that they span.

I don't think I have a favorite. Like anything, there's some tracks that you like more than others, but I think they're all great. The body of work that he created is remarkably consistently, really, really good.

MPc: During the live show it appears that you're doubling some of Billy's piano playing and other times doubling or accompanying the live horn section. How do you guys decide who plays what?

DR: Well, mostly he plays what he plays. So I find spots to play, things to play that enhance what he's already doing. A lot of the parts are derived from the record sonically and part-wise. And sometimes he has multiple piano-ish parts.

There's only a couple of places where we actually play dueling—same pianos at the same time. One is in "Don't Ask Me Why" in the piano break, we're actually both playing the part. And then there are some songs where I'm playing Rhodes and he's playing piano.

A lot of times I'll create my sounds to fit as a layer on top of his. For example, like the lead part in "Pressure," the patch that I'm using has no bottom in it. If you heard it by itself, it would sound kind of thin. But it sits perfectly on top of the chorus-y CP80 piano sound that he plays and the two parts together make it work. So my patch is meant to be played only with that piano sound.

MPc: What is your approach to enhancing live performance, with either backing tracks or sampled album parts?

DR: Well, we don't really have backing tracks at all. Billy is all about playing live. And the band—we have amazing musicians in the band. Everyone in this band is not only a great player, but knows how to play in a band. And it's two different skills. That's why it's so much fun to play with these guys—and girl—with this group. Because everybody is so proficient on their instrument and yet knows what not to play.

So we really are all about live. And that's why Billy enjoys throwing out a song without any notice. Because he likes the spontaneity of it, and we pull it off. And, if something goes wrong, he's the first one to laugh and tell the audience, "See? At least you know we're not prerecorded." And he makes it a moment. He says, "Look, we're really up here playing this." And we really are.

MPc: You just spoke about this a little bit: We know Billy likes to keep you all on edge during live performances. What's the most unexpected song he called out to play live that the band had to scramble to pull off?

DR: I think one that specifically comes to mind was when we were doing Last Play at Shea and Paul McCartney came up. I don't know if you know this story about us not knowing if Paul would get there in time for the show. It's all in Last Play at Shea, in the movie. Billy had asked him to do it; he couldn't make it. And that morning of the show, Paul McCartney called Billy and said, you know, I think I can do it. I only have one problem—I'm in London. I think I can get there in time, but I'm not sure.

So we didn't know through the whole show if he was going to make it in time. It's a great story, actually. [laughs] His flight was delayed and we started the show late intentionally to give him more time to get there. And they cleared out the airspace for him to land ahead of other planes, and then they whisked him through with a police escort to get to Shea Stadium from Kennedy Airport, made it like in 11 minutes. And this is all while the show is going on.

And then he finally pulls up and we hear over the headset about halfway through the show "the eagle has landed." We didn't really know if he was going to make it in time, so we had one contingent plan to do the show if he arrived and one if he didn't.

If he made it there on time, we were going to play "I Saw Her Standing There." So we ran over that in sound check. Fine.

So Paul shows up and he made it literally just in time for the first encore. They hand him his bass. Billy walks up, introduces him and he walks onstage. The crowd goes crazy and we played "I Saw Her Standing There." It was magic. I'm getting goosebumps just telling you about it. You should see it if you haven't seen Last Play at Shea. It's an amazing moment.

When we finished, Billy said to him, do you want to do another song? And Paul said, "No, no, no, it's cool, it's your show. Thanks. This was great." And he walked off the stage. But he didn't leave. So we did "Piano Man," which is how Billy used to always end the shows. When we finished "Piano Man," the crowd's still going crazy. And Paul hadn't left. So Billy walks over and he says to Paul, what do you think? And Paul said, "How about 'Let It Be?'" And Billy goes, "Great."

And Paul walked up and sat down at Billy's piano and started playing the intro to "Let It Be" and we had to play that song with him. Having never played it before. Not only with Billy, but now with Paul McCartney.

So that was a pretty cool moment. And of course, Billy is a kid in a candy store watching Paul play it, because he's such a Beatles fan. Billy sang harmonies and we just came in with the parts. It's a song we've all heard a million times. And for me, personally, I knew I had that cathedral-y type of sound that was going to come up and I thought, okay, let's see, what can I use? I'm thinking through my patches—ah, the intro to "Captain Jack," I have a pipe organ sound, I'll use that. So I scroll through to that song, set that up. I had a little bit of time, fortunately for me, until the part came up for me to think about how this would go. I kind of heard it a million times. And then all of a sudden we get to that spot and, okay, here we go—[baa, dum, dum, dum]. And so we played the song.

MPc: Awesome!

DR: And so that was very, very unexpected and it was in front of 56,000 people and it was being filmed. [laughs] But no pressure. [laughs]

MPc: Billy wrote a lot of rock and pop music from the '70s through the '90s. Then he seemed to suddenly stop recording pop music. Has he ever spoken about why he stopped and have you heard, is there any possibility of new pop music in the future?

DR: He's always writing this or that, but he stopped writing pop songs. He felt that he didn't have anything more to say. He doesn't want to write—just for the sake of doing it. So if one day he's inspired to write again, I think he will. But, you know, it's not like he's planning to do this or that or anything. It's all about the inspiration and, if he gets hit with the inspiration to write pop songs again, maybe he will. But, if not, then he would rather leave his catalog as it is. He's not going to do it just because everybody wants him to do it.

MPc: How did Billy Joel come to be the house band for Madison Square Garden?

DR: [laughs] Well, obviously, he's very popular here in the New York area and the idea of a residency had been kicked around for many years, but he wasn't interested in doing that in Vegas or Atlantic City or any of the typical things, and then the idea came about to possibly try doing something like this. And it was a bit of an experiment. Nobody really knew how it would go. But I think it's succeeded beyond anybody's wildest dreams. We didn't know how many shows we could do. We knew we could pretty much fill the first year, but here we are in the fourth year of doing it and still going strong. It's pretty remarkable.

MPc: It's the tour that never ends. [laughs]

DR: Yeah. Well, it's funny, because it doesn't feel like a tour because we're not really on the road. You know, we go and we do a show and we go home. We're doing three shows a month on a busy month. So everybody goes and we get together, we do a show once a month at Madison Square Garden, and once or twice elsewhere. And then we come back home.

So it doesn't feel like a tour. It's kind of a batch of shows. But it's interesting because you never really hit a stride, because you're not doing shows every day or every few days or whatever. So every show feels like it's the first show of a new leg of the tour, but it's also the last show of that leg because you go home afterwards. [laughs]

I think that it's a really unique group of musicians, Billy included, all of us, that can hit the stage cold, do a sound check and then we do the show. We don't run the whole show. We don't practice. We don't rehearse. We just do it. And it's pretty remarkable that we're able to do this.

And that goes beyond even the band. The crew is doing the same thing. Lights, sound, everybody from top to bottom on this whole tour, we do a show every couple of weeks or whatever and they put the whole thing up and we do it, like we just did it last night. And it comes out really good every time. There's a spontaneity about each one because everybody's on edge because nobody really ever hits autopilot.

Billy loves that spontaneity, and the crowd picks up on that spontaneity. So it makes the shows, I think, really exciting.

MPc: Does this leave you any time to work on any other projects with other artists? And related to that, what kind of music do you like work on when you're not busy with Billy Joel?

DR: Well, I do have a lot of extra time, obviously, from the schedule. So, for example, I just finished a project with Ethan Bortnick. He's a child prodigy that I work with, I'm his musical director. I did his last PBS special when he was 12 (called "The Power of Music"), which has been wildly successful, it's done incredibly well on PBS. One of the most viewed [television] concert specials of all time.

So, anyway, I just finished a new concert special with him called "Generations of Music". He's 16 now. We had an orchestra and a choir, and I love doing that stuff. He's brilliantly talented, he's great to work with, and the show came out great. I get to use a lot of my different skills—everything from orchestration to musical direction to post-production and studio work … it just encompasses a lot of my skill sets, so it's a lot of fun to do this.

Another is a band called Happy The Man. I did an album with them number of years ago called The Muse Awakens. I was able to slot that in in-between Billy tours. And that sort of keeps the inner progressive rock child alive in me, that loves playing that type of music whenever I get a chance to.

Along the way also I've had a chance in between to do other things like Broadway shows. I've also done synth programming for many other artists including Bruce Springsteen, I redesigned both of his keyboard rigs for the Wrecking Ball tour.

Once a rig is put together and it's on the road, you have to freeze everything.

All About The Gear

MPc: You've always innovated with your keyboard rigs, going from monosynths and electromechanical keyboards to samplers and music workstations to virtual instruments. Tell us about your current rig, which is predominantly computer-based.

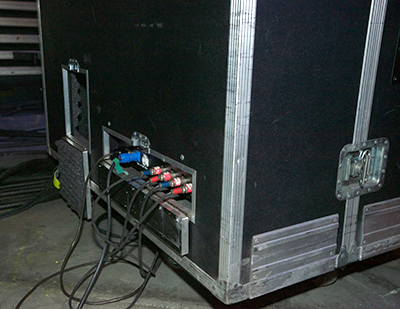

DR: Sure. The new keyboard rig is all computer-based. All my keyboards onstage are controllers. Since I am reliant on computers, and computers can crash, no matter how stable anything is—it happens, so I have two rigs running in real time. I have an A system and a B system that are identical, and they're both running at all times. If anything goes wrong with one, I hit a foot switch and I keep playing with the other one.

David's keyboards are all used as MIDI controllers today, though internal sounds can be called up from some of them in case of emergency.

The heart of the system is [Apple] Mainstage. That's what's kind of running the whole thing. And all of the synths live in software. Now, a lot of the sounds that I'm using are from my previous generations of the Billy rig. There aren't a lot of new sounds to create. His catalog is what it is and I had already created all of these sounds with modules and layers of analog synths and everything from previous generations of my keyboard rig. Those sounds were really good, I spent a lot of time creating them. There was no need to reinvent the wheel. So a lot of what I did in setting up this keyboard rig was to auto-sample those sounds into EXS24 and Kontact and port them over into software. Using Thunderbolt and Solid-State Drives it all works fine and the system is able to keep up with my playing. There's lots of layering in my sounds so multiple streams need to happen simultaneously in order to make it all work and feel like a musical instrument.

In addition to that I've also enhanced my system from a plug-in standpoint. Aside from using the old stuff, I'm also using Arturia's V collection. [Native Instruments] Kontact, as I mentioned, and Komplete. I think it's Komplete 9 that I'm using, and the reason I'm using an older version is because that's what was current when I designed this rig that I'm using now. Once a rig is put together and it's on the road, you have to freeze everything. Because once you get it to work, you don't want to be updating stuff. I'm not going to change MacOS. I'm not going to change the version of anything. Even if something cooler comes out, it has to stay as it is. So that's why I'm using an older version of Komplete.

MPc: So each rig really becomes a time capsule.

DR: It has to. Because we don't have the luxury of rehearsals. My gear spends 99% of its life in a truck. I get to get to it at sound check. Sometimes we have to add a new song or we're working on something or if we're going to have a guest artist, I have to set up some sounds quickly, whatever. There is no time to install a new version of something and properly test it. In a rehearsal atmosphere, you can try stuff and, if you crash and burn, you restart, you recover, it's fine. But we don't have that.

So, I can't update the rig in that environment at all. Unless we have downtime and I have enough time to get the whole thing here at my house, set it up and really, really put it through its paces. Then I can make a change like that. But for the most part, it's frozen.

MPc: Running your whole rig off of virtual instruments, do you find yourself worrying more or less about the system crashing versus when you toured with a physical keyboard rig?

DR: I worry all the time. [laughs] Onstage. I am 100% on my toes at all minutes of the show thinking about the gear. Because as long as it's working, it's a whole lot of fun. But if something's not right, I have to deal with it. I have to troubleshoot it. And I have to figure out what to do, how to get through that song, and how to get through the show if there's a problem.

So, yeah, I'm having a great time focused on the music and really loving it. It's not really that I'm "worried" but I'm thinking about it all the time. I'm very, very conscious of how my gear is working, and I'm monitoring everything. I have a computer on stage that's set to screen-sharing. My main computers that are running the show are off stage, but I'm able to watch what's going on at all times.

A lot of times when something's going to go wrong with a computer, with the software, I can feel it, sometimes before it happens. It's like the patches start to respond a little bit sluggishly and I can just feel something's not right. So then I need to kick into action. And it has happened where things go wrong.

MPc: Can you tell us about one of your scariest technical equipment failures on stage and how you dealt with it? Or do you just say, knock on wood, we haven't had to yet? [laughs]

DR: Well, no, there's been some scary moments. I mean, there were times in the old days before I had a real-time backup where my whole rig went down. So, because of the possibility of that ever happening, I keep my organ (a Hammond XK3C, and the Leslie) independent of my MIDI rig. So, what I did is I just played organ on that song. I played the parts. It wasn't the right sound, but I contributed to the song and there was something coming from me while my tech restarted the whole rig. But it takes a long time, especially in the older days, for computers to restart and everything. The rig was down probably for the better part of a song or maybe a song and a half, which, when it's happening, feels like eternity. But I played organ.

So, yeah, that's the scariest moment, what to do if you have nothing. But in this case, I've prepared for that possibility by having an extra set of redundancy because I have the two computers. Additionally I also have patches in my Kurzweil 2600 which, even though I'm using it as a controller during the show, in the event that both computers were to simultaneously crash—which has happened once or twice—I can then hit another button and I can switch to use the outputs of my Kurzweil and I can get through a couple of songs if I need to.

MPc: With so many great virtual instruments, and the backup in place that you have, why do you even bother taking a real Leslie out on the road anymore?

DR: Because nothing sounds like that! [laughs] Nothing sounds like a Leslie. There is a phenomenon that occurs from the Doppler effect of air moving with a rotating horn and speaker. Nothing else sounds like that. There are really, really good simulators out there. But it's not the same. It's just not the same. And, fortunately, I'm on a tour where the y're willing to carry a Leslie. It really suits Billy's music.

y're willing to carry a Leslie. It really suits Billy's music.

One of the things that I do to really capture that realDoppler effect is I have an ISO booth road case. The road case is 2-1/2 times the size of the Leslie, with the Leslie mounted in the center of it so there's enough air inside the road case that the sound can actually get thrown around and you get a very natural Leslie sound inside the road case. The case is pretty big, but the Leslie sounds great as a result. A lot of guys will mic a Leslie inside a road case, but it ends up sounding kind of choked. So I came up with this design. The Leslie stays in the case, mic-ed up and everything, and you just plug in the outside of the case. You never have to open up the case unless there's a problem.

So, basically, it just wheels onto the truck and wheels off the truck and you just plug it in and you're ready to go. It's pretty cool.

MPc: You built Billy Joel's piano rig for him, as well. Can you tell us a little bit about that rig? And what kind of backups are in place for his piano?

DR: Sure, so his rig consists of two [Muse] Receptors running Ivory and Komplete. And also a Kurzweil PC2R. So the Receptors are running redundantly. And the controller is a Kawaii VPC-1 [custom built into an acoustic grand piano housing]. So that's what he's playing. And the patches are being changed from an iPad with Unrealbook.

And that's it. Over the course of time, some of the Kurzweil patches are still being used and it's a mix of that and the other elements. Every song has its own setup, even if it uses the same patch. That way, if a song comes up that we're doing, say, a half-step down or a whole step down, when the patch gets recalled, it's recalled in the right key. So every patch is changed by song title so you can't have a situation where it ends up with the wrong transposition or something like that.

MPc: Do you change his patches?

DR: No, his tech does it.

MPc: Let's talk about some sounds that are notable in the keyboard realm of Billy Joel. The synth riff on "Pressure" is pretty iconic. How was the original sound made and how did you then go about recreating that sound?

DR: Well, when I went about recreating it, I didn't have the luxury of asking him, actually, about any of the sounds. I just listened to them and recreated it however it made sense to me.

So the way I created that particular sound is in layers. I used [Oberheim] Matrix 1000s, analog synths. There's a little hint of a synth-y sort of piccolo trumpet in there to give it a little bit of that brittle character, and there's a harpsichord-y type tone to give it some attack. There's no bottom in it, as I was explaining earlier, so that that patch sits nicely on top of the piano.

After you asked me the other day, I asked Billy what he used. It was an OBX synth. So I was right-on in capturing the oscillators with the Oberheim sound. They also doubled the line with plucked mandolins playing the line, and that's what I heard as the harpsichord layer that I created that way. So I was pretty close in the way I recreated it, even though I didn't have any information.

MPc: Nice. And what about the mono-synth lead from "The Entertainer?"

DR: So that is a MiniMoog that he played originally. I copied that patch on my mini-Moog many years ago by ear and then sampled it. It originally lived in the K2600. Over the years I started modifying it just to give it a little bit of a different character, to have a little more cut to translate well in an arena. So I added another analog synth layer with a little bit of portamento and some delay.

MPc: Were there any other particularly challenging Billy Joel album sounds to recreate? Like, when you listen to the record and you're thinking, "Hmmm."

DR: Well, some of it is how to first create the sound and then get that sound to translate in an arena and in a stadium, and to sit right in the mix within the current instrumentation of the band - which is not exactly the same as the record. It's really close and it sounds like it, but it's slightly different instrumentation, the tones are a little bit different, thus the mix is different.

So, when I create my patches, I'm always thinking about the mix. Where is the sound that I'm creating going to sit in the mix? Is it up front? Is it in the back? Is it supporting the guitars? Is it enhancing the piano? What's its role in the mix? When I create my sounds, I always have that in mind with how I construct it.

For example, when I was doing the sound for the "Angry Young Man" solo. Now that one, I first copied the exact patch, which was originally a MiniMoog. I tried that a few times and it sounded good, but it needed a little bit more meat to really cut through the power of a live band in an arena. So I added a couple of other layers—again, same type of ideas I did with "The Entertainer," although the big difference with those two is that in "The Entertainer," the part is mostly exposed. There's a lot of acoustic guitar behind it, there's piano, and sometimes there's very little else going on.

But in "Angry Young Man," during the solo, it's big in that section, and the sound has to cut over this giant bed of what's going on underneath it. So I added some other synth layers to it just to give that original MiniMoog sample a little bit more beef to cut through the band and translate in a big arena.

MPc: Something I noticed in particular was that the band's live sound was really much larger, heavier, and more rocking than the classic recordings. It was really impressive how—the energy level that the band brings to it.

DR: Yeah. I think that's the chemistry of this group of players that's creating that. And it works. Unfortunately, I never get to sit in the audience and listen to what we sound like. [laughs]

MPc: And not to take anything away from the contributions that Liberty DeVitto made over the years, but your new drummer— I think his sound and style really has a big impact on that rock vibe.

DR: Yeah, yeah. He's a great drummer, Chuck [Burgi], and I of course have a long history of playing with him. We were in Rainbow together and my band Red Dawn, he was the drummer for that. We toured with Enrique Iglesias. We worked on Movin' Out together. He and I have a long, long musical history, so it's really fun to have him in this band. He's such a great player and, yeah, he's just rock-solid and, what I said earlier about knowing how to play in a band, he gets it. As does everybody.

By the time you get further down the road in your life, you'll be using gear that doesn't exist.

History

MPc: Your career got its start when you replaced Don Airey in Rainbow, at the start of the '80s. How did a young Berklee grad even land that audition?

DR: [laughs] Well, right place at the right time, I suppose? I don't know. A friend of mine knew a friend of Ritchie's [Blackmore] and that's how I found out that he was looking for a keyboard player. So I sent him a cassette of my senior piano recital—which I had done two years earlier when I was a sophomore. [laughs] It's all classical stuff. Some Liszt and some other things. I knew that Ritchie liked classical music.

I also sent him a tape of my cover band at the time, which in those days we were playing a lot of Kansas—more proggy stuff, and some heavy stuff. Not quite as heavy as Rainbow, but, I sent him that. He liked it enough to invite me down to an audition, which was like a cattle call audition. And then, you know, I got the callback and it was down to me and one other guy and then I got the gig. I was 20 when I joined Rainbow.

MPc: That must have been intimidating!

DR: I wasn't intimated, no. I was excited. I thought it was cool. I was, like, this is great. I just do what I do. I don't think I got intimated because I went down and I did what I did and, if what I did is right for what he was looking for, then I'll get the gig. And if it's not, then that doesn't mean that I'm less good at what I do, it just means maybe I wasn't right for that band.

My advice to a lot of players out there, especially younger kids, is when you guys do auditions, go in and do it as best you can, go in with that attitude. But if you don't get the gig, it's not the end of the world. Maybe you're just not the right type of player that they were looking for stylistically—or who knows. But it doesn't mean that you're less of a musician or less qualified. It just means it wasn't the right fit. So you go back home and get back on the horse and something else will come along.

MPc: You were the keyboard player for two of the most iconic world tours of the '80s. Cyndi Lauper's True Colors tour and Robert Palmer's Heavy Nova tour. Tell us a little bit about your experience on those tours and the rigs you used to support them.

DR: Well, we'll start with Cyndi Lauper. Her music was very keyboard-heavy with lots of parts going on. It was completely different from Rainbow and from a tour [I did] with Little Steven in-between there, as well.

I changed the rig around because at that time MIDI was kind of coming into its own. That was the first time that I was using a dedicated controller, the [Yamaha] KX76, that was a brand-new thing that had come out, that now you had a keyboard that was dedicated to being a controller. There were other synths, as well, but that was the first time I carried a rack of modules to get the different sounds. The brains of that system were the MEP4s, the Yamaha MIDI Event Processors. I don't know if you know that—might be before your time, even. Yamaha made it and it was in one rack space, one in by four out. There were four processors and each one of those processors could control whatever MIDI synth was connected to it. Turn it on and off. Transpose. Splits. You can create layers by overlapping different zones, filter out and control volume, set up program changes. All the stuff that the [Opcode] Studio 5 and Mainstage have all built in. This was the first time that anything could ever do that. And you needed that to control the whole rig.

I ended up using three of those because that controls up to 12 instruments. I think I had like 10 modules and keyboards total, something like that.

So the KX76 sent a program change to the three MEP4s. And from that program change, each of those went to their own respective programs and they sent out the proper individual program changes and set up the splits and and volume information for each one of the slave modules.

MPc: Do you remember off the top of your head a couple of the rack modules you were using back in the day?

DR: Yeah. I know I had a [Yamaha] TX816, a Korg EX8000, a Roland D550 and an MKS70. I know I was using the [E-Mu] Emulator 2 in those days, the keyboard. The [Yamaha] DX7. I think I was using the [rev] 1 at that time. And I had a {Roland] Juno 106, which was a big part of Cyndi's sounds. Especially on her first record.

MPc: The arpeggiated type stuff? Was that Juno?

DR: Like, "All Through the Night?" Yes, I believe so. But I didn't use an arpeggiator. I played it. [laughs]

MPc: Nice! [laughs]

DR: I couldn't… I didn't want to have to rely on the drummer playing to a click and getting a sync track going. Nowadays it's a common thing, but in those days, it wasn't really refined. I was, like, I'm just going to play this, because I can play it right in time and Cyndi was fine with that. We started the first rehearsal and I played it and she never said anything about it—she was happy about it. So if you look at the live videos, I'm actually playing all of the arpeggiated parts on "All Through the Night." Great, great song. It was a fun part to play.

We didn't have any playback running or timecode or any of that stuff in those days.

MPc: No, not then. And how about the Robert Palmer tour?

DR: Robert Palmer, on that tour the Emulator 2 got replaced with a Casio FZ1 for samples. And the DX7 II replaced the original DX7. I was still using the KX76. And then a lot of the other modules in the rack were still the same thing. Those 2 tours happened very close together, I think it was only a few months in between, when one ended and the next one started, so the rig was fairly similar.

MPc: You've mentioned in previous interviews that, while you were attending Berklee, you played in a band with Steve Vai. Now I know that you later played with him on Whitesnake's 1989 release, Slip of the Tongue. And then you also followed that up by playing on his groundbreaking album, Passion and Warfare. What's it like working with a guitar virtuoso like Steve Vai?

DR: Well, Steve's great. He's a close personal friend because we knew each other and played in a band together when we were 18, before either of us had any success. We go all the way back to then. So we're good friends. We rarely get to play together, but every once in a while, we get the opportunity and it's a lot of fun.

I was actually at his studio working on Passion and Warfare and I played on a bunch of tracks for that album. We had a great time doing it. He knows exactly what he wants. He either has charts or he shows me exactly what he wants me to play or he says "do something like this." He has a very distinct vision of what he wants. And that's kind of fun and challenging in its own way to keep delivering what he's hearing in his head. I love working with him.

As we finished up the tracks for Passion and Warfare he said, hey, wait a minute, you know what? While you're here, I'm working on this Whitesnake album and we need some keyboards. It was for the title track, "Slip of the Tongue." In those days it was all two-inch tape, so he changed reels of tape and put the Whitesnake master up. And, just like that, I played on a Whitesnake album.

MPc: Wow.

DR: [laughing] Talk about being in the right place at the right time. So, yeah, that's how that happened. The Whitesnake album ended up finished and released first, but I actually played on both of those in the same sessions.

MPc: What about the more recent release, Story of Light?

DR: So, on Story of Light, I played piano on the title track. And that was really a neat thing because I did it here in my studio and he was in L.A. in his studio. We did it over Skype. I had the Pro Tools session here and I had him on my laptop talking and listening to what I was doing. He had a very specific vision of what he wanted and it was pretty complex. He had this solo all mapped out that he had already recorded and doubled.

We went through it bar by bar and he would say, now, I want something like this. And then… oh, that's good, okay, let's record that measure. Okay, and then we went through the whole thing and it ended up being a really unique-sounding piano part. The whole second half of the track we're sort of playing together but the parts are intertwined. It's acoustic piano, which is not something he typically uses on his records. It was a lot of fun to do that.

MPc: You also worked with another guitar virtuoso, Yngwie J. Malmsteen, playing on his 1996 record, Inspiration. And you orchestrated his Millennium Concerto Suite. Now, Yngwie isn't known for being the easiest artist to collaborate with, but he must have had some great level of trust in your skills to allow you the opportunity to orchestrate his concerto. So, tell us about working with Yngwie on that.

DR: Well, yeah, he does have quite a reputation. I was playing on his Inspiration album and I was working with him and that's when he told me he had the idea for this concerto. And I was, like, this is so up my alley. He says, I know you do this stuff, are you interested? Yeah!

So that's kind of where the whole thing came from, the whole concept of it was born. I worked on that pretty much full-time for nine months. The interesting challenge was that Yngwie doesn't read music. So, in order to show him what I had done and make sure that he was comfortable with what I created—I would first create the orchestration for each movement, write the whole thing out and then I built the "Rosenthal Philharmonic," I called it in those days, which was all Kurzweil modules at that time, and I played every single one of the orchestral parts and recorded it. Then I could go down to his place in Florida and he could play over my demo of it, to make sure that he liked the way it sounded and was happy with the arrangement. He would make some comments, try this, try that. I want this to change, I want an extra section, whatever. And I would go back and modify it and come back. So that's how we worked until we got through the whole thing and he was happy with the whole arrangement.

When we were doing most of that stuff, it was really just me and him in the room and we got along fine. He's a brilliantly talented musician. And, when there's no distractions around and it's just the two of us sitting in a room, we really connected musically very well. I think the concerto came out great. It really was a great opportunity for me to do that and I'm very proud of the work. It's really a cool piece, a sort of traditional concerto written for a 90-piece orchestra with full choir and the lead instrument is Strat through Marshall. [laughs]

MPc: [laughs] Yeah.

DR: Which, from an orchestral standpoint of view and an orchestrator's standpoint of view, was an interesting challenge. Because a Strat through Marshall is a pretty big sound. So when he was playing the lines that I knew he was going to play, I had to carve holes in the orchestration to make space for his parts so that he wasn't fighting for space with the orchestra or vice-versa. So that was the challenge of that: to create it such that the orchestration would wrap around his guitar and have space for his parts to shine as the featured instrument without competing.

MPc: I've noticed there's a recurring theme in your approach to music: that you're always composing with the mix in mind. You're thinking like an engineer while playing as a musician.

DR: Yeah. If you ask me, a great mix starts with a great arrangement. So it's very much harmonious, the arrangement of a song, the orchestration, the mix, the sounds that are chosen, the sonic composition of the whole thing, they all work together.

MPc: I understand you almost became a member of Dream Theater years ago. Can you share a little bit of the backstory on that?

DR: Sure. It was actually after Kevin Moore left the band. I know those guys from way back when and I had been in touch with them. They asked me to join, which I would have loved to do from a musical standpoint, it would have been a lot of fun, but I was kind of committed with Billy at that time. I was on the River of Dreams tour and the timing just didn't work out.

So they ended up getting Derek Sherinian and brought me in to do some programming to get the sounds they wanted—that's how I worked on the Change of Seasons EP.

MPc: Years ago you put together an AOR rock group of your own, Red Dawn, featuring drummer Chuck Burgi and bassist Greg Smith. The CD received excellent reviews. Have you ever thought about doing a new band project today or perhaps a follow-up to that Red Dawn release?

DR: There's been a lot of offers to do a follow-up, but we've all gone off in different directions. That style of music doesn't really have a big place in the world, sadly, because it's great stuff. Not just my record, but that whole genre of stuff.

I just don't see that in the cards to do another Red Dawn record. I think that record stands well on its own. I'm really proud of it. Probably if it came out maybe three or four years earlier, it would have been huge. But that's the way it goes. It came out right when the whole tide was turning stylistically in the world.

But, yeah, it was a lot of fun to make that record. Great musicianship on that. I really enjoyed making that record and, to this day, it's fun to pop it on every once in a while and listen to it.

MPc: Earlier, you mentioned working with the prog band, Happy the Man. Where does that fit into everything?

DR: Happy the Man was another side project that I did. And that was really a blast, musically, to do that. They were one of my favorite bands of all time when I was growing up. I discovered them when I was at Berklee. It's kind of a cool story because I always wanted to be in that band, but I didn't know the guys. But I wished that someday I could be in the band. And so much so, I used to transcribe all of Kit Watkins' solos—he was a big inspiration on me as a player. I used to listen to their music constantly and learn all the parts.

And then one day a guy I knew at Berklee, he said, Oh, Happy the Man? I know those guys, they're my buddies. And I practically lifted him up by his shirt and I was, like, "You're going to take me to meet these people." And he did. [laughs]

So we went and met them. The band had already broken up by that point in time, sadly. But Rick Kennell and Stanley Whitaker were in a band called Vision, playing in upstate New York. We went to go see them play and I met them at their gig. Really nice guys. And I just kept in touch with them through the years. Eventually I met Frank Wyatt and Ron Riddle as well. And I kind of got to know everybody. Although the band was but a distant memory at that point.

Fast forward all the way to the late '90s and I don't remember, '99, something like that, maybe 2000. And they wanted to do a reunion. And Kit Watkins didn't want to do it. So I was, like, guys, I'm your guy, look no further. I would love to do a record with you guys. So that's how that came about. And we got together and we played, and we made a record called, The Muse Awakens—which was originally released in 2004, and has just been reissued in 2017.

A side note story—the first track on that album, "Contemporary Insanity," I actually wrote that back when I was at Berklee. Because I wanted to be in Happy the Man then. So I had written that song then and I just put it aside. I'd say it was 80, 90 percent the same thing. Then when I started working with the band, I said, you know, guys, I have this song that I wrote. And they loved it. So I finished it up and the song that I wrote all the way back in the early '80s ended up as the lead track on the album, The Muse Awakens.

MPc: Who are some other artists today that, if the phone rang, you'd love to go out and play with?

DR: Well, actually, I got asked by Ritchie Blackmore to do a Rainbow reunion, which I would have been happy to do but it didn't coincide with my Billy schedule, unfortunately. I would have loved to do that. It would have been a lot of fun..

MPc: You still have the wardrobe? [laughs]

DR: [laughs] I think I'd have to get something newer. [laughs] I don't have the hair anymore, either.

The interesting thing about the music business is you never know where your career is going to take you. You asked earlier about advice for young students. You can't script your career. You don't know what's going to come. So the best thing that a young musician can do today is master your craft. Really learn everything you can while you have time to practice and study about music, about theory. If you're a keyboard player, learn how synths work. Learn not only what they do but why they do it. Because by the time you get further down the road in your life, you'll be using gear that doesn't exist. All of the gear that I'm using today? Not one single piece existed when I was a student. But all the concepts are the same. All the theories are the same. You just apply it.

So it's really important to learn your craft really well when you're young. And then you got to roll with it. You got to see where the career takes you. I could have never thought, "Well, first I'll play with Rainbow, then I'll tour with Cyndi Lauper and…" You can't. You don't know what's going to happen. But it all kind of fell into place and then I ended up here with Billy Joel, and 24 years later I'm still here doing this. So who could have predicted this? You can't. But it's worked out pretty good.